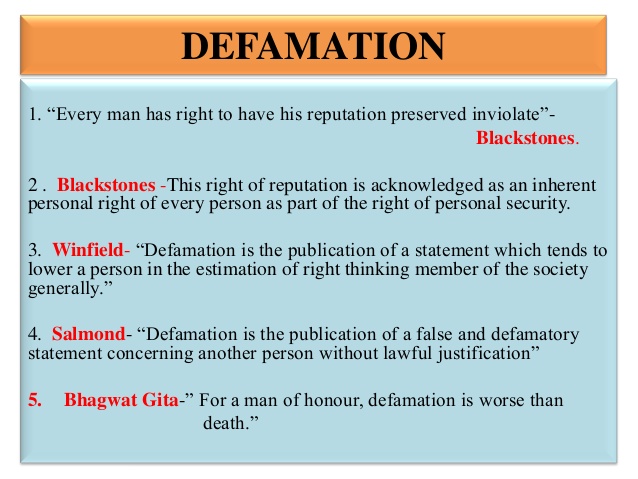

Defamation (sometimes known as calumny, vilification, libel, slander ) is the oral or written communication of a false statement about another that unjustly harms their reputation and usually constitutes a tort or crime.

Under common law, to constitute defamation, a claim must generally be false and must have been made to someone other than the person defamed. Some commmon law jurisdictions also distinguish between spoken defamation, called slander and defamation in other media such as printed words or images, called libel.

Libel and slander are the legal subcategories of defamation. Generally speaking, libel is defamation in written words, pictures, or any other visual symbols in a print or electronic (online or Internet-based) medium. Slander is spoken defamation. The advent of early broadcast communications (radio and television) in the 20th century complicated this classification somewhat, as did the growth of social media beginning in the early 21st century.

Generally, defamation requires that the publication be false and without the consent of the allegedly defamed person. Words or pictures are interpreted according to common usage and in the context of publication. Injury only to feelings is not defamation; there must be loss of reputation. The defamed person need not be named but must be ascertainable. A class of persons is considered defamed only if the publication refers to all its members—particularly if the class is very small—or if particular members are specially imputed.

Usually, liability for a defamation falls on everyone involved in its publication whose participation relates to content. Thus, editors, managers, and even owners are responsible for libelous publications by their newspapers, whereas vendors and distributors are not.

Right to Freedom of speech and expression

Article 19 (1) (a) of the Constitution of India guarantees to every citizen of India the right to freedom of speech and expression. The Supreme Court has recognised that the liberty of press is an essential part of this freedom. Article 19 (2) of the Indian Constitution, which lists out those subjects on which reasonable restrictions can be made on the right to free speech, includes defamation. And, in India, the law recognises both civil and criminal defamation as valid restrictions.

The law on defamation

Sections 499 and 500 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (“IPC”) collectively criminalize defamation. Section 499 is the charging section and the punishment is prescribed under Section 500. Section 499 stipulates that whoever, by words either spoken or intended to be read, or by signs or by visible representations, makes or publishes any imputation concerning any person intending to harm, or knowing or having reason to believe that such imputation will harm, the reputation of such person, is said, except in the cases provided, to defame that person. It provides three exceptions to the offence: one, imputation of truth which public good requires to be made or published; two, public conduct of public servants; and, three, conduct of any person touching any public question.

Section 500 says that whoever defames another shall be punished with simple imprisonment for a term, which may extend to two years, or with fine, or with both. Both of these provisions were challenged as unconstitutional before the Supreme Court. However, their validity was upheld in Subramanian Swamy v. Union of India & Ors (2016). This judgment has been widely criticized, because, among other things, it ignores the chilling effect that criminalizing defamation has on free speech and the free press. The judgment also ignores the fact that in almost no other constitutional democracy is defamation a criminal offence.

But as a result of this judgment in Subramanian Swamy, and, as a result of the development of the law of criminal defamation, over the years, an onerous burden has come to be placed on persons who are charged with the offence and courts have been reluctant to quash proceedings at the first instance. At the same time, though, the scope of civil defamation in India has been narrowed with a view to advancing the value of free expression.

In R. Rajagopal v. State of Tamil Nadu (1994). In this case, a popular Tamil magazine, Nakkheeran, field a writ petition under Article 32 of the Constitution, seeking to restrain the state government and the prison authorities from taking action that might halt the publication of an autobiography of Auto Shankar, who, while on death row, had written a letter to the magazine. Here, the Court was specifically concerned with the question of how to balance the freedom of press vis-à-vis the right to privacy of the Indian citizens. In this context, questions also arose over the scope of the right of the press to criticize and comment on the acts and conduct of public officials. The Supreme Court referred to various decisions of American courts, including New York Times v. Sullivan, on the freedom of press, and, finally, amongst other things, held that the State or its officials cannot impose a prior restraint on the press/media, and that, Government or its other organs cannot maintain a suit for damages. Through this judgment, the Court also effectively adopted the test in Sullivan for proceedings of civil defamation. This was recognised by a division bench of the Madras High Court in R. Rajagopal v. J. Jayalalitha(2006),

You must be logged in to post a comment.