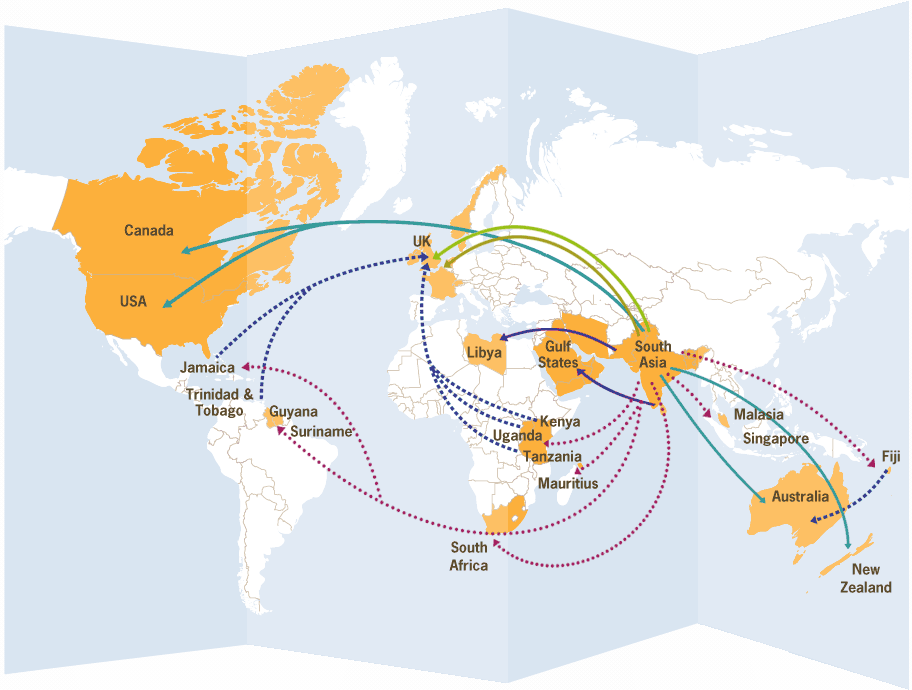

Caste has migrated with the South Asian diaspora to firmly take root in East and South Africa, Mauritius, Fiji, Suriname, the Middle East, Malaysia, the Caribbean, the United Kingdom, North America, and other regions.

Among migrant communities in North America and Europe, caste ideologies are perpetuated by families returning to India to seek out marriage partners within their own caste. U.S.-based matrimonial services, including regional conventions, are burgeoning alongside a growing population of Indian origin. Families openly advertise their caste preference in the matrimonial sections of Indian community papers in North America and Europe (a practice quite common within India as well), as well as on Internet matchmaking sites.

In the United States, a rising number of caste-based groups-each with chapters throughout many major cities-also points to the importance of caste as an identifier for migrant Indian communities. Such caste-based associations in the United States are providing funds and political support for a resurgence of caste fundamentalism in South Asia as well.

In Britain emigrant Dalits must also worship in segregated temples and have thus formed an umbrella group for low-caste temples-Guru Ravidass UK. Twenty-two of these temples withheld (and ultimately redirected) funds raised for earthquake victims in Gujarat due to incidents of caste discrimination in the distribution of earthquake relief.

Also in Britain caste tensions frequently erupt between high-caste Punjabis (Jats) and low-caste Punjabis (Chamars). Physical violence has also been known to erupt following intermarriage between the two communities. Caste consciousness becomes especially problematic given the sizable population of both Jats and Chamars in the United Kingdom. According Sat Pal Muman, a presenter at the September 2000 International Dalit Human Rights Conference in London, inquiries about one’s caste background are often made in privately run or Jat-run educational institutions and places of employment. In the city of Wolverhampton incidents of upper-caste Jats refusing to share water taps or make any physical contact with lower-caste persons have also been reported. At a sports competition in Birmingham in 1999 Jats reportedly refused to eat food that came from the Chamar community.

In Suriname, Indians of Dalit-descent continue to be largely distinguished by their various caste-based occupations.123 Chamars traditionally worked as drum beaters, beggars, hawkers, and shoemakers; Pallen as landless laborers; Dhobis as washers; Collies as porters; and Dasis as house servants. A higher-caste group includes Kurmis as cultivators, Ahir as cow herders, and Chettyar as weavers, barbers, shopkeepers, and moneylenders. The third and highest caste category consists of priests, scribes, and schoolmasters.

In Mauritius, with its large concentration of people of Indian origin, social organization is based on family, kinship networks, and “to a not negligible extent, caste-based organization.” Caste-based considerations have also been reported in the political and employment sector.

Caste distinctions play a role in both private life and political organization within Malaysia‘s minority “Indian” community although the extent of its influence on Malaysian Indian society is the subject of considerable debate. Caste considerations are most obvious in the private sphere, particularly in the community’s attitudes towards intermarriage. Many families seeking to arrange marriages place matrimonial ads that include caste requirements, and marriage brokers may be expected to take caste into account when finding suitable matches. As one researcher observed, “Caste has, indeed, such a strong hold in marriage matters that intercaste marriages between different categories of higher caste status sometimes do not take place with parents’ approval, much less between higher and lower caste members. Abolition of caste discrimination in this area remains a distant dream.” Though interactions outside the home seem to take place without much emphasis on caste, within the home contact with castes thought to be polluting may be quite limited. Some families, for example, refuse to dine with or accept food and drinks from people they suspect of being lower caste.

Mass migration of higher and lower-caste Indians to Bahrain, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, and other Gulf states has brought with it vestiges of the caste system as well.