Formation of the Bishnoi sect— India’s original environmentalists

Bishnoism originated in the 1485AD by Saint Guru Jambheshwar in theThar Desert of Rajasthan, India. Long before the world came to know about the environmental crises, Bishnois have been cognizant of man’s relationship with nature and the importance to maintain its delicate balance. It is remarkable that these issues were considered, half a century ago by Bishnoi visionaries. No other secthas given this level of importance to environment value, protection and care.

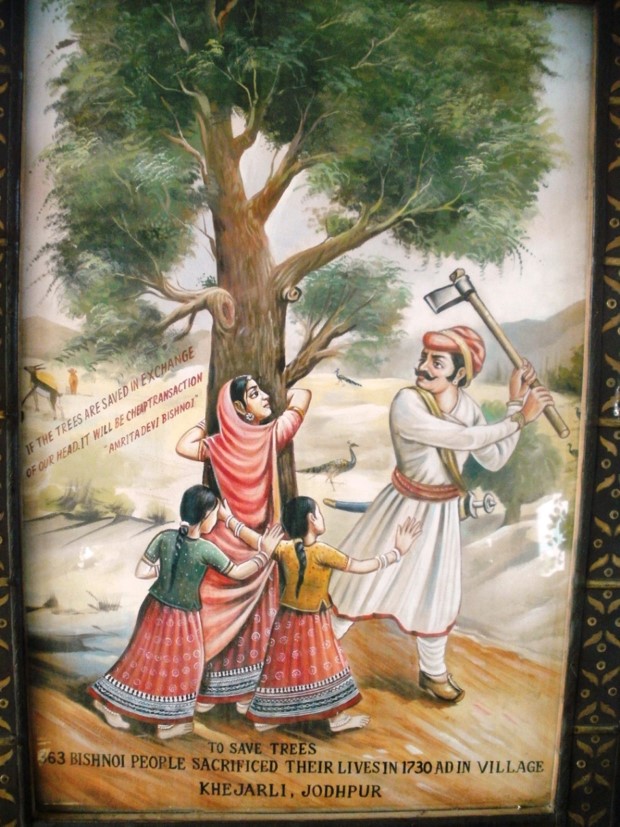

Not many of us know that the concept of Tree Huggers and Tree-Hugging, have roots within the Bishnoi community. The famous ‘Chipko Movement’ was inspired by a true story of a brave lady called Amrita Devi Bishnoi who refused to let the kingsmen cut the trees and sacrificed her life to save the trees.

This sacrifice not only inspired the “Chipco Andoloan” by Sunder Lal Bahuguna but also the Indian government. The “Amrita Devi Bishnoi Smrithi Paryavaran Award” for contributing to environment conservation is given to those who have significantly contributed for environment conservation.

The Bishnois are one of the first organized communities that have collectively sought for eco-conservation, wildlife protection, and green living. The ideals and tenets of the bishnois and bishnoism mentioned in the 29 religious tenets are very crucial and relevant to our ever evolving world.

The social concern, in medieval Rajasthan, manifested itself in various forms. To unite the people for a common cause, Guru Jambheswar Ji advised 29 principles to become a Bishnoi. The word ‘Bishnoi’ stands for ‘bish’ which means 20 and ‘noi’ which means 9; derived from these 29 principles out of which 6 principles are dedicated to environmental protection and compassion for all living beings.

Of the 6 tenets that focus on protecting nature, the two most profound ones are:

Jeev Daya Palani – Be compassionate to all living beings.

Runkh Lila Nahi Ghave – Do not cut green trees.

Though these rules date back centuries, they still hold the morals and the beliefs for which the bishnois stand and are more than relevant to the environmental problems faced in today’s world.

Conservation as a practical necessity

In the arid and semi-arid regions of western Rajasthan, Bishnoism as a sect has over the ages has not only proposed, but also internalised their practices in an effort to usher in new practices of conservation ethics in Rajasthan. A majority of the Bishnoi rules suggested maintenance of harmony with the environment, like the prohibition on cutting green trees and animal slaughter. One plausible explanation is that the economy was primarily sustained by animal rearing. Hence, any slaughter, even during droughts, would have affected their means of livelihood.

Similarly, the cutting of green trees was prohibited, as it would scale back the availability of green fodder for the cattle, especially in the dry region where natural vegetation was very thin and sparse. Jambhoji’s teachings, which were in line with the interests of the folk, became immensely popular primarily in the arid regions of Bikaner and Jodhpur. The number of his followers increased manifold in these regions. His principles became so influential that the rulers of these states were forced to respect his teachings and sermons. The Bishnois have since long proposed for placing restrictions and punishments for cutting trees.

Rajasthan’s landscape demands dependence on agricultural and cattle-rearing practices. The conservation of natural vegetation of the region helped sustain superior breeds of cattle for export to other regions, exports such as sheep for wool, and camels for transport proved beneficial. Trade and commerce were also an important component of these economies as is evident in the nature of taxation where non-agricultural production was also taxed extensively (Kumar 2005).

Protection of wildlife and animals

The Bishnois consider the blackbucks as pavitra, or sacred. They follow what is perhaps the only environment-friendly religion in the world and recognise the rights of all kinds of birds, animals and trees and believe in living with peace and harmony with them. Reports show that in 2016, over 1,700 people who were involved in wildlife crimes in Rajasthan were arrested owing to the tireless efforts of the bishnoi community.

Some of their commandments mention to “provide shelters for abandoned animals to avoid them from being slaughtered in abattoirs,” making clear the Bishnoi’s reverence of all life on the planet.

The Khejarli massacre

Khejarli or Khejadli is a village situated in Jodhpur district of Rajasthan, just 26 km southeast of the main city of Jodhpur. The name of the town is derived from khejri trees, which were in abundance in the village. In the year 1730 AD (Vardhan 2014), the king of Jodhpur sent-out his army to cut trees in order to build his palace. When his army started to cut down and log a Bishnoi forest, the bishnois organised a non-violent protest, offering their bodies as shields for the trees. The soldiers had warned that anyone intending to stand in their way would share the fate of Amrita (or Imarta/Imarti as she is often also referred to by the locals) and her three daughters who had taken the bold step of hugging trees following their mother’s action, and had been killed by the soldiers. Men, women and children from 83 different villages stepped forward, embraced the trees and sacrificed themselves one after the other.

The army’s axes had already slain 363 people, when the king, Maharaja Abhay Singh, hearing the whole incident and their perseverance and courage, halted the logging and declared the Khejarli region a preserve, issued a royal decree engraved on a tambra patra (a letter engraved on a copper plate), prohibiting the felling of trees and hunting in the Bishnoi areas. The Bishnois as well as non-Bishnois consider the tambra-patra declaration as a victory of the communities efforts at conservation.

Till date, the Bishnoi community commemorates and celebrates this collective sacrifice as a symbolic victory in Khejarli by maintaining the place as a heritage site. An annual fair is organised at the village near Jodhpur, which also maintains a functional temple. In 1988, the Government of India commemorated the massacre formally, by naming the Khejarli village as the first National Environmental Memorial (Clarke 1991). A cenotaph now stands at the site as a memorial to the Bishnoi lives lost at the massacre site, which is collectively maintained through community funding as well as by private donations.

Incidentally, Imarta Devi, the first woman who died in defence of the khejri trees during the 1730 Khejarli massacre, uttered her last words as follows: Sar sāntey rūkh rahe to bhī sasto jān (even if one were to get their head severed to save a tree, still it is a cheap bargain).

You must be logged in to post a comment.