What Are the Nazca Lines?

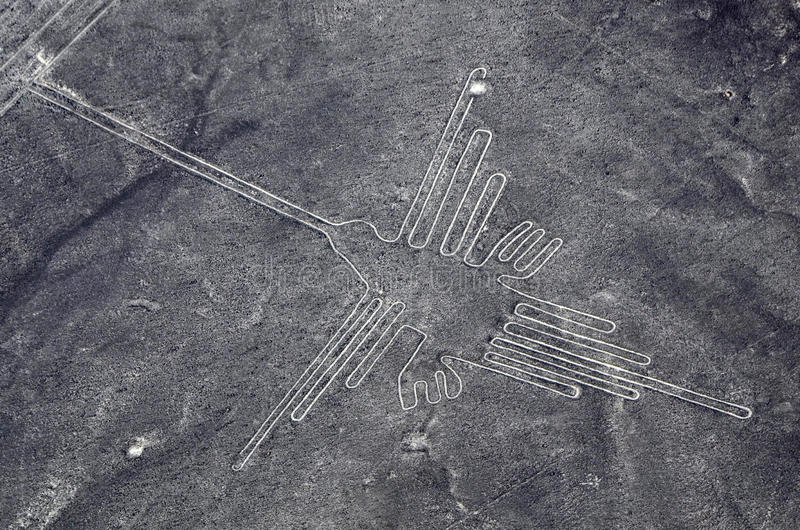

There are three basic types of Nazca Lines: straight lines, geometric designs and pictorial representations.

There are more than 800 straight lines on the coastal plain, some of which are 30 miles (48 km) long. Additionally, there are over 300 geometric designs, which include basic shapes such as triangles, rectangles, and trapezoids, as well as spirals, arrows, zig-zags and wavy lines.

The Nazca Lines are perhaps best known for the representations of about 70 animals and plants, some of which measure up to 1,200 feet (370 meters) long. Examples include a spider, hummingbird, cactus plant, monkey, whale, llama, duck, flower, tree, lizard and dog. The Nazca people also created other forms, such as a humanoid figure (nicknamed “The Astronaut”), hands and some unidentifiable depictions.

How the Nazca Lines Were Created

Anthropologists believe the Nazca culture, which began around 100 B.C. and flourished from A.D. 1 to 700, created the majority of the Nazca Lines. The Chavin and Paracas cultures, which predate the Nazca, may have also created some of the geoglyphs.

The Nazca Lines are located in the desert plains of the Rio Grande de Nasca river basin, an archaeological site that spans more than 75,000 hectares and is one of the driest places on Earth.

The desert floor is covered in a layer of iron oxide-coated pebbles of a deep rust color. The ancient peoples created their designs by removing the top 12 to 15 inches of rock, revealing the lighter-colored sand below. They likely began with small-scale models and carefully increased the models’ proportions to create the large designs.

Purpose of the Nazca Lines

More recent research suggested that the Nazca Lines’ purpose was related to water, a valuable commodity in the arid lands of the Peruvian coastal plain. The geoglyphs weren’t used as an irrigation system or a guide to find water, but rather as part of a ritual to the gods—an effort to bring much-needed rain.

Some scholars point to the animal depictions—some of which are symbols for rain, water or fertility and have been found at other ancient Peruvian sites and on pottery—as evidence of this theory.

In 2015, researchers presenting at the 80th annual meeting of the Society for American Archeology argued that the purpose of the Nazca Lines changed over time. Initially, pilgrims heading to Peruvian temple complexes used the geoglyphs as ritual processional routes. Later groups, as part of a religious rite, smashed ceramic pots on the ground at the point of intersection between lines.

You must be logged in to post a comment.