The caste system, the joint family system and the village system of life are often regarded as the three basic pillars of the historical Indian social system. The caste system as a form of stratification is peculiar to India. The caste system is an inseparable aspect of the Indian society. It is peculiarly Indian in origin and development. Caste is closely connected to Hindu philosophy and religion, customs and traditions, marriage and family, morals and manners, food and dress habits, occupations and hobbies. The caste system is believed to have divine origin and sanctions. The caste stratification of the Indian society has had its origin in the Chaturvarna system. According to the Chaturvana doctrine, the Hindu society was divided into four main varnas namely: the Brahmins, the Kshatriyas, the Vaishyas and the Shudras. The caste system owes its origin to the varna system.

Definition of Caste as given by some prominent sociologists:

MacIver and Page: “When status is wholly predetermined so that men are born to their lot without any hope of changing it, then the class takes the extreme form of caste.”

C. H. Cooley: “When a class is somewhat strictly hereditary, we may call it caste.”

D. N. Majumdar and T. N. Madan have said that caste is a ‘closed group’.

Perspectives on caste system in India:

The perspectives on the study of caste system include Indological or ideological, social anthropological and sociological perspectives. The Indological or ideological perspective takes its cue from the scriptures about the origin, purpose and future of the caste system, whereas the cultural perspective of the social anthropologist looks the origin and growth of caste system, its development, and the process of change in its structure or social structural arrangements as well as in the cultural system also view caste system not only as unique phenomenon found in India, but also in ancient Egypt, medieval Europe, etc. But the sociological perspective views caste system as a phenomenon of social inequality. Society, especially, Hindu social system has certain structural aspects, which distribute members in different social positions. It shows concerns with growth of the caste system. Many sociologists put forward their theory of caste with respect to Indian society. Some prominent sociologists in this regard are, G. H. Ghurye, Louis Dumont and M. N. Srinivas.

G. H. Ghurye theory of caste:

G. H. Ghurye is regarded as the father of Indian sociology. His understanding of caste in India can be considered historical, Indological as well as comparative. In his book, “Caste and race in India” he agrees with Sir Herbert Risley that “Caste is a product of race that came to India along with the Aryans”. According to him caste originated from race and occupation stabilized it. Ghurye explains caste system in India based on six distinctive characteristics:

1. Segmental division of society: Under caste system, society is divided into several small social groups called castes. Additionally, there are multiple divisions and subdivisions of caste system.

2. Hierarchy: According to Ghurye, caste is hierarchical. Theoretically, Brahmins occupy the top position ad Shudras occupy the bottom. The castes can be graded and arranged into a hierarchy on the basis of their social precedence.

3. Civil and religious disabilities and privileges: This reflects the rigidity of the caste system. In a caste system, there is an unequal distribution of disabilities and privileges among its members. While the higher castes enjoy all the privileges, the lower castes suffer from various types of disabilities.

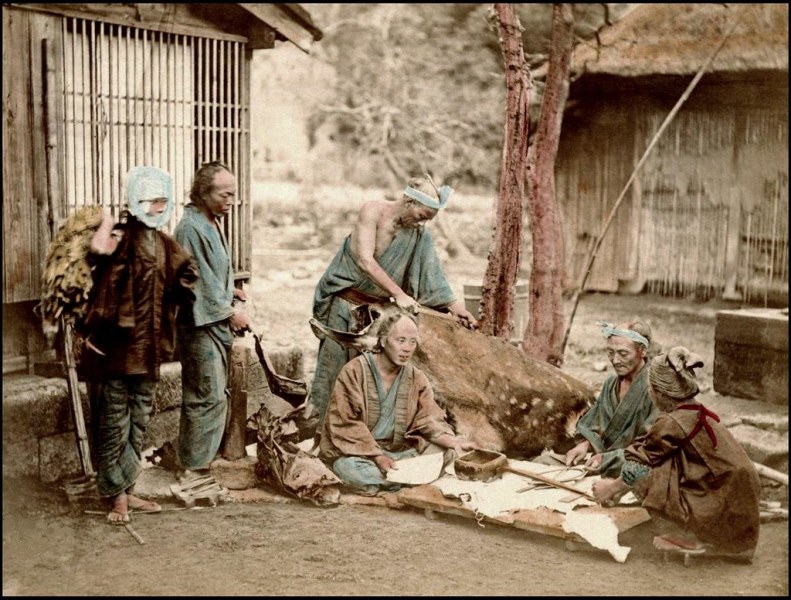

4. Lack of unrestricted choice of occupation: The occupations in caste system are fixed by heredity and generally members are not allowed to change their traditional occupations. The higher caste members maintain their supremacy in their jobs and do not allow other caste group to join in the same occupation.

5. Restriction on food, drinks and social intercourse: Restriction on feeding and social intercourse are still prevalent in Indian society. There are two types of food I.e., Kacha (cooked) food and Pakka (raw) food upon which certain restrictions are imposed with regard to sharing.

6. Endogamy: Every caste insists that its members should marry within their own caste group.

Louis Dumont theory of caste:

Louis Dumont was a French Sociologist and Indologist. His understanding of caste lays emphasis on attributes of caste that is why; he is put in the category of those following the attributional approach to the caste system. Dumont says that caste is not a form of stratification but a special form of inequality, whose essence has to be deciphered by sociologists. Dumont identifies hierarchy as the essence of caste system. According to Dumont, Caste divides the whole Indian society into a larger number of hereditary groups, distinguished from each other and connected through three characteristics:

1. Separation on the basis of rules of caste and marriage,

2. Division of labor, and

3. Gradation of status.

He also put forward the concept of ‘pure’ and ‘impure’ which was widely seen in the Caste ridden society. The Brahmins were assigned with priestly functions, occupied the top rank in the social hierarchy and were considered “pure” as compared to other castes. The untouchables being “impure”, were segregated outside the village and were not allowed to drink water from the same wells from which the Brahmins did so. Besides this, they did not have any access to Hindu temples and suffered from various disabilities.

M. N. Srinivas theory of caste:

M. N. Srinivas was one of the first-generation Indian sociologists in post-Independence period. Srinivas approach to study of caste is attributional I.e., analyses caste through its attributes. He assigned certain attributes to the caste system. These are:

1. Hierarchy

2. Occupational differentiation

3. Pollution and Purity

4. Caste Panchayats and assemblies

5. Endogamy

Besides caste, Srinivas looks for yet another source or manifestation of tradition. He found it in the notion of ‘dominant caste’. He had defined dominant caste in terms of six attributes placed in conjunction:

• Sizeable amount of arable land,

• Strength of numbers,

• High place in the local hierarchy,

• Western education,

• Urban sources of income and

• Jobs in the administration

Of the above attributes of the dominant caste, the following two are important:

• Numerical strength, and

• Economic power through ownership of land

He also introduced the concept of “Brahmanisation” wherein the lower caste people imitate the lifestyle and habits of the Brahmins. This concept was further changed to “Sanskritisation”.

These are a few theories of caste system that prevailed before the rise of modern India owing to the revolutions undergone during the British rule.

You must be logged in to post a comment.