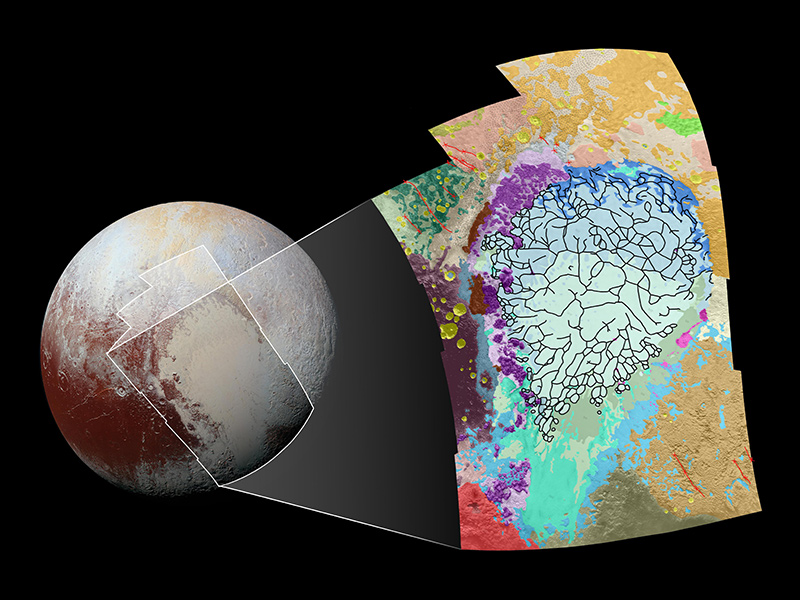

Pluto – which is smaller than Earth’s Moon – has a heart-shaped glacier that’s the size of Texas and Oklahoma. This fascinating world has blue skies, spinning moons, mountains as high as the Rockies, and it snows – but the snow is red.

Soon after Pluto was discovered in 1930, it was designated a planet, the ninth in our solar system. After Pluto was discovered, many astronomers presumed it to have been responsible for the perturbations they have observed in Neptune’s orbit. It was these perturbations that actually prompted the search for a planet beyond it. However, further observations determined that it was smaller than initially assumed. Also, after American astronomer James Christy discovered Pluto’s largest moon, Charon, in 1978, astronomers were able to determine Pluto’s mass and realized that it was a lightweight and didn’t exert a gravitational influence powerful enough to have induced the observed perturbations. Pluto was found to be smaller and less massive than all the other planets. Moreover, its orbit is highly inclined (17 degrees) relative to the ecliptic, the plane defined by Earth’s orbit around the Sun. The other planetary orbits have smaller inclinations.

As telescopes got bigger and better, and were able to take clearer pictures of distant bodies like Pluto, astronomers began to suspect that Pluto was much, much smaller than the other planets. By the time the second Kuiper Belt object was discovered in 1992, astronomers knew that Pluto was even smaller than Earth’s moon, but it had been called a planet for so long that it retained its planetary status.

Astronomers had also known for decades that Pluto’s orbit actually crosses Neptune’s orbit. None of the other planets cross each other’s orbits, so why was Pluto’s orbit different?

Over the next few years, dozens and then hundreds more Kuiper Belt objects were discovered by astronomers, until finally, in 2005, astronomer Mike Brown discovered Eris, which is even bigger than Pluto.

In the early 21st century, astronomers were finding bodies of comparable size beyond Pluto, such as Sedna, Eris, Makemake, and others. These discoveries prompted the question: should the IAU confer planetary status on all these other worlds? In August 2006, the IAU convened its triennial meeting in Prague. Toward the end of this meeting, they voted on the adoption of Resolution 5A: “Definition of ‘planet.” By this newly adopted definition, a body has to fulfill three requirements to be designated a planet. First, a body has to have established a stable orbit around the Sun. Thousands of bodies meet this condition. Secondly, a body has to have developed a spheroidal shape. When a body is sufficiently large and massive, gravity will mold it into a spheroid. Pluto fulfills this condition. Third, and finally, the body has to have cleared its debris field. It has to be sufficiently massive so as to incorporate all proximate objects into it. Pluto fails on this condition, as its orbit passes close to or even within the Kuiper Belt, a region from which short periods comets originate. By adopting resolution 5A, the IAU demoted Pluto, firmly established the other eight planets as planets, and disqualified all the bodies beyond Pluto, all in one fell swoop.

Although the recent observations by the New Horizons craft has shown us that Pluto is larger, more geologically dynamic, and contains a thicker atmosphere than once believed, it still doesn’t fulfill the third condition within Resolution 5A. The IAU will have to adopt a revised definition of planet in order to confer planetary status back onto Pluto.

Of course, some defiantly maintain that Pluto is still a planet and no resolution shall induce us to change our minds.

You must be logged in to post a comment.