Thomas Newcomen, a Devonshire blacksmith, developed the first successful steam engine in the world and used it to pump water from mines. His engine was a development of the thermic siphon built by Thomas Savery, whose surface condensation patents blocked his own designs. Newcomen’s engine allowed steam to condense inside a water-cooled cylinder, the vacuum produced by this condensation being used to draw down a tightly fitting piston that was connected by chains to one end of a huge, wooden, centrally pivoted beam. The other end of the beam was attached by chains to a pump at the bottom of the mine. The whole system was run safely at near atmospheric pressure, the weight of the atmosphere being used to depress the piston into the evacuated cylinder.

Newcomen’s first atmospheric steam engine worked at conygree in the west midlands of England. Many more were built in the next seventy years, the initial brass cylinders being replaced by larger cast iron ones, some up to 6 feet (1.8 m) in diameter. The engine was relatively inefficient, and in areas where coal was not plentiful was eventually replaced by double-acting engines designed by James Watt. These used both sides of the cylinder for power strokes and usually had separate condensers. James watt was responsible for some of the most important advances in steam engine technology.

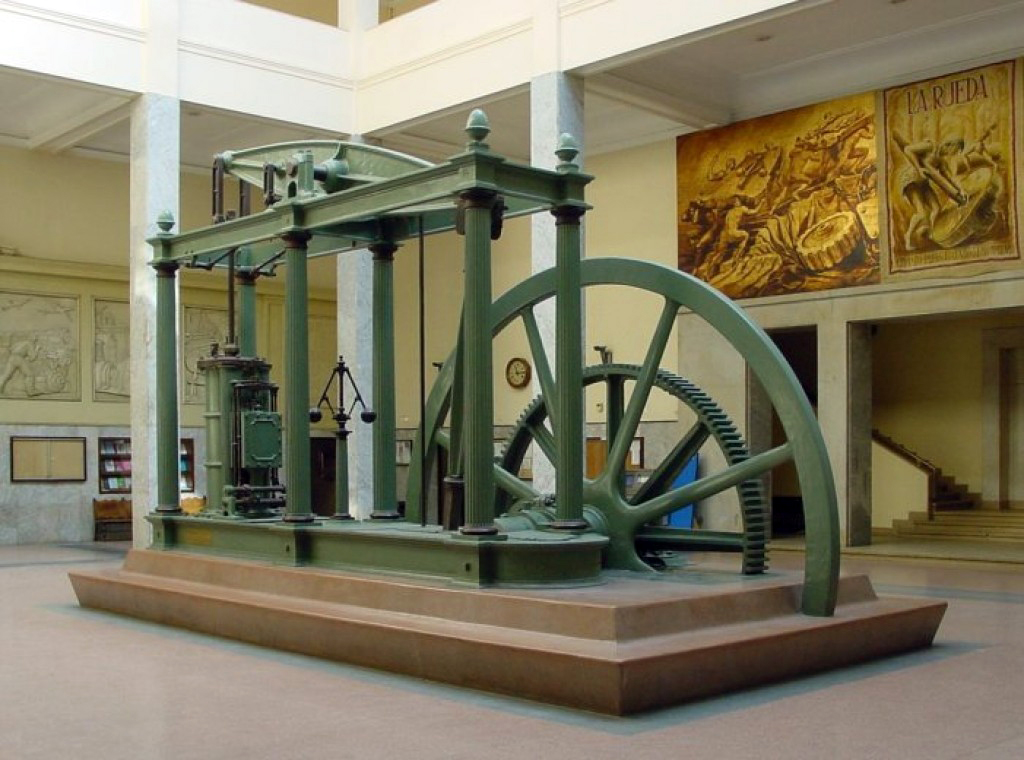

In 1765 watt made the first working model of his most important contribution to the development of steam power, he patented it in 1769. His innovation was an engine in which steam condensed outside the main cylinder in a separate condenser. The cylinder remained at working temperature at all times. Watt made several other technological improvements to increase the power and efficiency of his engines. For example, he realized that, within a closed cylinder, low pressure steam could push the piston instead of atmospheric air. It took only a short mental leap for watt to design double-acting engine in which steam pushed the piston first one way, then the other, increasing efficiency still further.

Watt’s influence in the history of steam engine technology owes as much to his business partner, Matthew Boulton, as it does to his own ingenuity. The two men formed a partnership in 1775, and Boulton poured huge amount of money into watt’s innovations. From 1781, Boulton and watt began making and selling steam engines that produced rotary motion. All the previous engines had been restricted to a vertical, pumping action. Rotary steam engines were soon the most common source of power for factories, becoming a major driving force behind Britain’s industrial revolution.

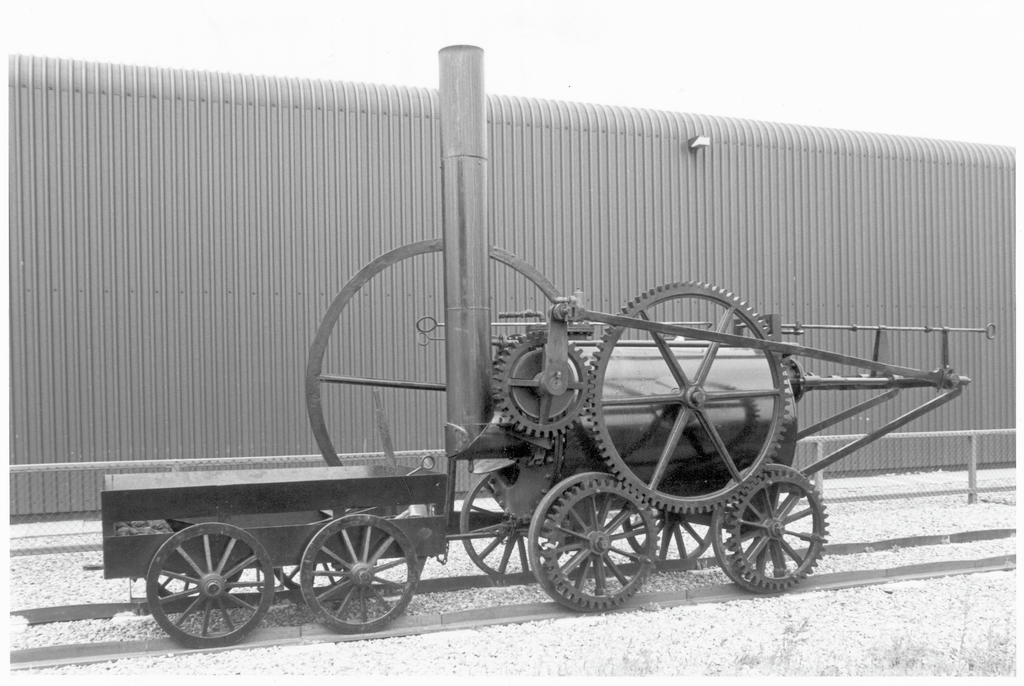

By the age of nineteen, Cornishman Richard Trevithick worked for the Cornish mining industry as a consultant engineer. The mine owners were attempting to skirt around the patents owned by James Watt. William Murdoch had developed a model steam carriage, starting in 1784, and demonstrated it to Trevithick in 1794. Trevithick thus knew that recent improvements in the manufacturing of boilers meant that they could now cope with much higher steam pressure than before. By using high pressure steam in his experimental engines, Trevithick was able to make them smaller, lighter, and more manageable.

Trevithick constructed high pressure working models of both stationary and locomotive engines that were so successful that in 1799 he built a full scale, high pressure engine for hoisting ore. The used steam was vented out through a chimney into the atmosphere, bypassing watt’s patents. Later, he built a full size locomotive that he called puffing devil. On December 24, 1801, this bizarre-looking machine successfully carried several passengers on a journey up Camborne hill in Cornwall. Despite objections from watt and others about dangers of high pressure steam, Trevithick’s work ushered in a new era of mechanical power and transport.

You must be logged in to post a comment.