Science of the Alpha Centauri system. The two stars that make up Alpha Centauri, Rigil Kentaurus and Toliman, are quite similar to our sun. Rigil Kentaurus, also known as Alpha Centauri A, is a yellowish star, slightly more massive than the sun and about 1.5 times brighter. Toliman, or Alpha Centauri B, has an orangish hue; it’s a bit less massive and half as bright as the sun. Studies of their mass and spectroscopic features indicate that both these stars are about 5 to 6 billion years old, slightly older than our sun.

Alpha Centauri A and B are gravitationally bound together, orbiting about a common center of mass every 79.9 years at a relatively close proximity, between 40 to 47 astronomical units (that is, 40 to 47 times the distance between the Earth and our sun).Must Watch Sky Events in 2021

In comparison, Proxima Centauri is a bit of an outlier. This dim reddish star, weighing in at just 12 percent of the sun’s mass, is currently about 13,000 astronomical units from Alpha Centauri A and B. Recent analysis of ground- and space-based data, published in 2017, has shown that Proxima is gravitationally bound to its bright companions, with a 550,000-year-long orbital period.

Proxima Centauri belongs to a class of low mass stars with cooler surface temperatures, known as red dwarfs. It’s also what’s know as a flare star, where it randomly displays sudden bursts of brightness due to strong magnetic activity.

In the past decade, astronomers have been searching for planets around the Alpha Centauri stars; they are, after all, the closest stars to us so the odds of detecting planets, if any existed, would be higher. So far, two planets have been found orbiting Proxima Centauri, one in 2016 and another in 2019. A paper published in February 2021 reported tantalizing evidence of a Neptune-sized planet around Alpha Centauri A, but so far, it has not been definitively confirmed.

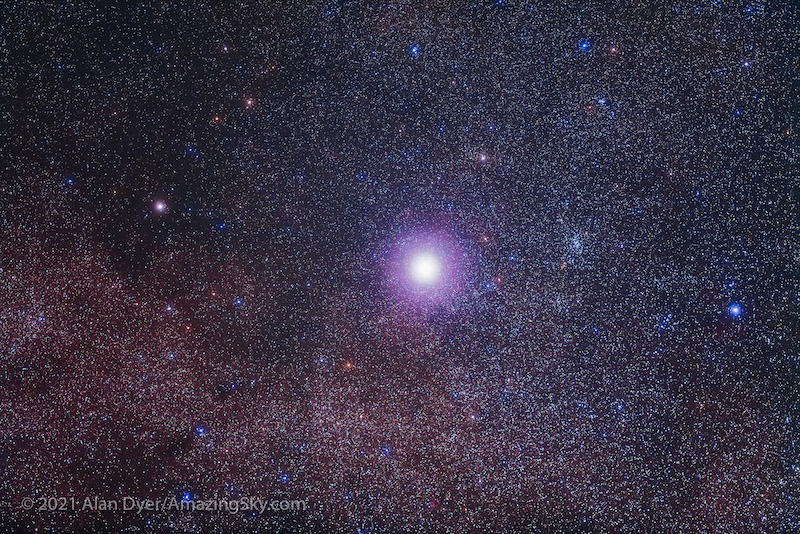

How to see Alpha Centauri. Unluckily for many of us in the Northern Hemisphere, Alpha Centauri is located too far to the south on the sky’s dome. Most North Americans never see it; the cut-off latitude is about 29° north, and anyone north of that is out of luck. In the U.S. that latitudinal line passes near Houston and Orlando, but even from the Florida Keys, the star never rises more than a few degrees above the southern horizon. Things are a little better in Hawaii and Puerto Rico, where it can get 10° or 11° high.

But for observers located far enough south in the Northern Hemisphere, Alpha Centauri may be visible at roughly 1 a.m. (local daylight saving time) in early May. That is when the star is highest above the southern horizon. By early July, it reaches its highest point to the south at nightfall. Even so, from these vantage points, there are no good pointer stars to Alpha Centauri. For those south of 29° N. latitude, when the bright star Arcturus is high overhead, look to the extreme south for a glimpse of Alpha Centauri.

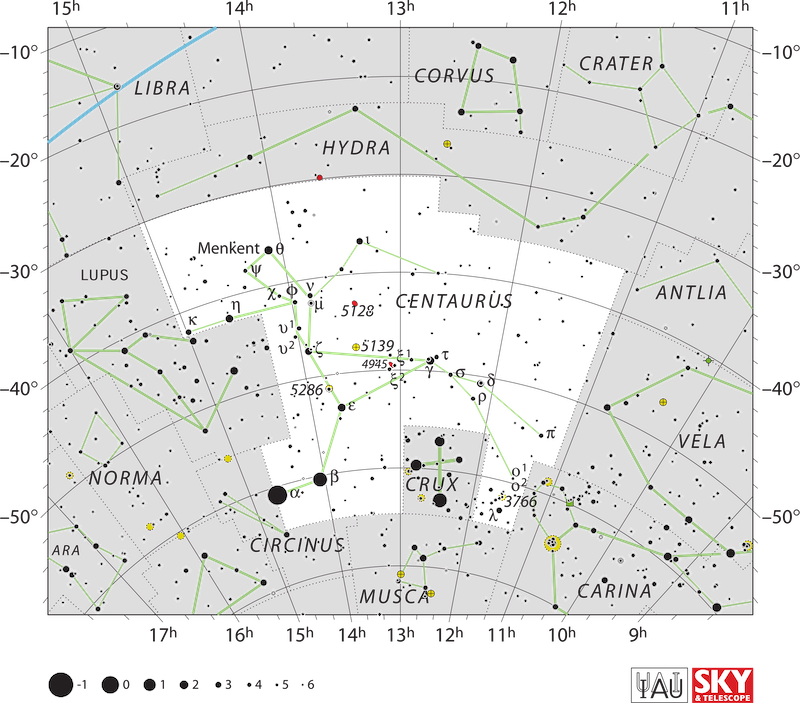

Observers in the tropical and subtropical regions of the Northern Hemisphere can find Alpha Centauri by first identifying the distinctive Southern Cross. A short line drawn through the crossbar (Delta and Beta Crucis) eastward first comes to Hadar (Beta Centauri), then Alpha Centauri. Meanwhile, in Australia and much of the Southern Hemisphere, Alpha Centauri is circumpolar, meaning that it never sets.

Alpha Centauri in mythology. Alpha Centauri has played a prominent role in the mythology of cultures across the Southern Hemisphere. For the Ngarrindjeri indigenous people of South Australia, Alpha and Beta Centauri were two sharks pursuing a sting ray represented by stars of the Southern Cross. Some Australian aboriginal cultures also associated stars with family relationships and marriage traditions; for instance, two stars of the Southern Cross were through to be the parents of Alpha Centauri.

Astronomy and navigation were deeply intertwined in the lives of ancient seafaring Polynesians as they sailed between islands in the vast expanse of the South Pacific. These ancient mariners navigated using the stars, with cues from nature such as bird movements, waves, and wind direction. Alpha Centauri and nearby Beta Centauri, known as Kamailehope and Kamailemua, respectively, were important signposts used for orientation in the open ocean.

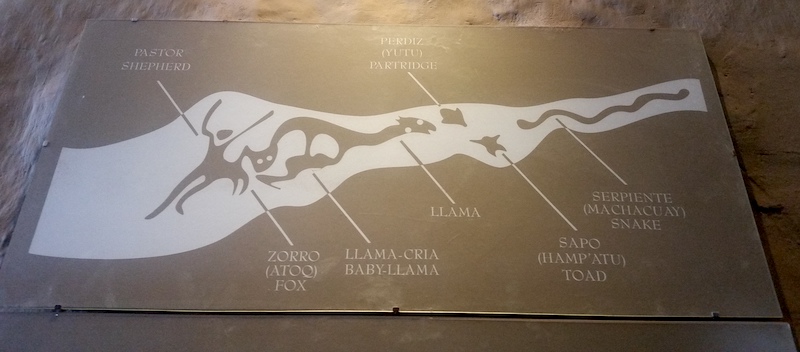

For ancient Incas, a llama graced the sky, traced out by stars and dark dust lanes in the Milky Way from Scorpius to the Southern Cross, with Alpha Centauri and Beta Centauri representing its eyes.

Ancient Egyptians revered Alpha Centauri, and may have built temples aligned to its rising point. In southern China, it was part of a star group known as the South Gate.

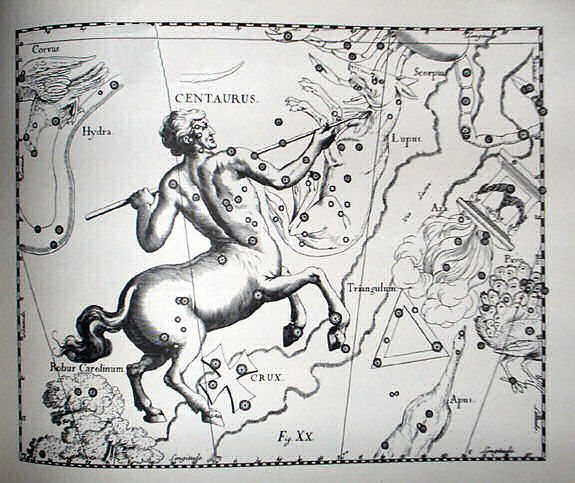

Alpha Centauri is the brightest star in the constellation Centaurus, named after the mythical half human, half horse creature. It was thought to represent an uncharacteristically wise centaur that figured in the mythology of Heracles and Jason. The centaur was accidentally wounded by Heracles, and placed into the sky after death by Zeus. Alpha Centauri marked the right front hoof of the centaur, although little is known of its mythological significance, if any.

Alpha Centauri’s position is RA: 14h 39m 36s, Dec: -60° 50′ 02″

Bottom line: Alpha Centauri is actually two binary stars that are quite similar to our sun. A third star that’s gravitationally bound to them is Proxima Centauri, the closest star to our sun.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/1d/94/1d94a50d-2cad-4307-8c01-c337ead1fef9/feb15_j03_antikythera.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.