A wave begins as the wind ruffles the surface of the ocean. When the ocean is calm and glass like, even the mildest breeze forms ripples, the smallest type of wave. Ripples provide surfaces for wind to act on, which produces larger waves. Stronger winds push the nascent waves into steeper and higher hills of water. The size a wave reaches depends on the speed and strength of the wind. The length of time it takes for the wave to form, and the distance over which it blows in the open ocean is known as the fetch. A long fetch accompanied by strong and study winds can produce enormous waves. The highest point of a wave is called the crest and the lowest point the trough. The distance from one crest to another is known as the wavelength.

Although water appears to move forward with the waves, for the most part water particles travel in circles within the waves. The visible movement is the wave’s form and energy moving through the water, courtesy of energy provided by the wind. Wave speed also varies; on average waves travel about 20 to 50 Mph. Ocean waves vary greatly in height from crest to trough, averaging 5 to 10 feet. Storm waves may tower 50 to 70 feet or more. The biggest wave that was ever recorded by humans was in Lituya bay on July 9th, 1958. Lituya bay sits on the southeast side of Alaska. A massive earthquake during the time would trigger a mega tsunami and the tallest tsunami in modern times. As a wave enters shallow water and nears the shore, it’s up and down movement is disrupted and it slows down. The crest grows higher and be gins to surge ahead of the rest of the wave, eventually toppling over and breaking apart. The energy released by a breaking wave can be explosive. Breakers can wear down rocky coast and also build up sandy beaches.

Why does a tide occur?

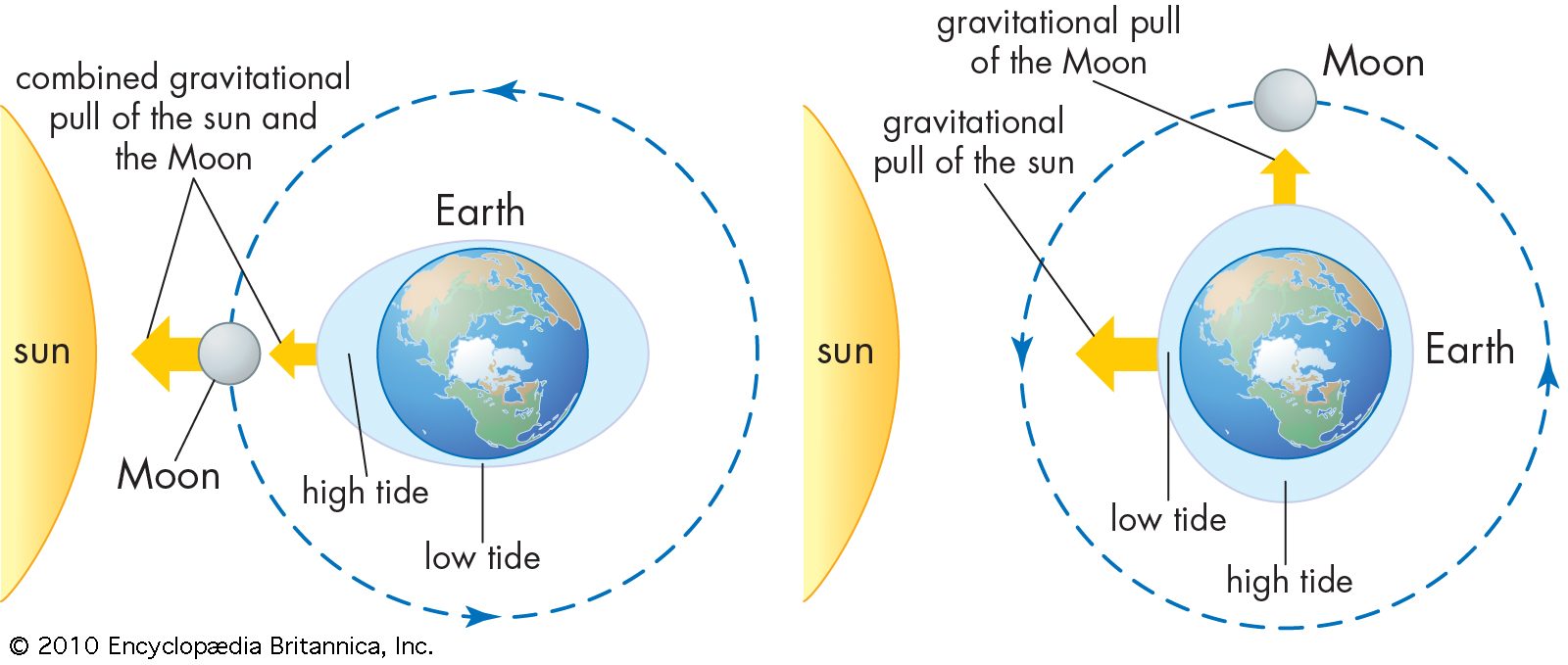

Tides are the regular daily rise and fall of ocean waters. Twice each day in most locations, water rises up over the shore until it reaches its highest level, or high tide. In between, the water recedes from the shore until it reaches its lowest level, or low tide. Tides respond to the gravitational pull of the moon and sun. Gravitational pull has little effect on the solid and inflexible land, but the fluid oceans react strongly. Because the moon is closer, its pull is greater, making it the dominant force in tide formation.

Gravitational pull is greatest on the side of earth facing the moon and weakest on the side opposite to the moon. Nonetheless, the difference in these forces, in combination with earth’s rotation and other factors, allows the oceans to bulge outward on each side, creating high tides. The sides of earth that are not in alignment with the moon experience low tides at this time. Tides follow different patterns, depending on the shape of the seacoast and the ocean floor. In Nova Scotia, water at high tide can rise more than 50 feet higher than the low tide level. They tend to roll in gently on wide, open beaches in confined spaces, such as a narrow inlet or bay, the water may rise to very high levels at high tide.

There are typically two spring tides and two narrow tides each month. Spring tide of great range than the mean range, the water level rises and falls to the greatest extend from the mean tide level. Spring tides occur about every two weeks, when the moon is full or new. Tides are at their maximum when the moon and the sun are in the same place as the earth. In a semi-diurnal cycle the high and low tides occur around 6 hours and 12.5 minutes apart. The same tidal forces that cause tides in the oceans affect the solid earth causing it to change shape by a few inches.

You must be logged in to post a comment.