Music has always been an important part of Indian life. The range of musical phenomenon in India extends from simple melodies to what is one of the most well- developed “systems” of classical music in the world. There are references to various string and wind instruments, as well as several kinds of drums and cymbals, in the Vedas. Music has a place of primacy in Indian culture: in traditional aesthetics, music is often allegorised as ‘the food of the soul’. It symbolises India’sremarkable diversity in cultural, linguistic and religious terms and embodies the historical tides that have shaped its contemporary pluralism. India’s vastness and diversity, Indian Music encompass numerous genres, multiple varieties and forms which include classical music, folk, rock, and pop.

Desi culture (from the Sanskrit desa, ‘land’ or ‘country’) is prominent across the world today and has had an ‘exotic’ allure for centuries, from its cultural domination of China and Southeast Asia (from 1stC BCE) to its ascent in the ‘Oriental’ imaginary of the ‘West’, culminating in the New Age movement (late 20thC CE). Since the mid-20thC, there has been a great deal of interaction between Indian music and the West and Hindustani music, in particular, emerged as the fundamental archetype of ‘Eastern’ tradition in the ‘World Music’ phenomenon.

By the 16th century, the classical music of the Indian subcontinent eventually had split into two traditions: Hindustani (North Indian classical music) and Carnatic (South Indian classical music). However, the two systems tended to share more common features rather than differ from one other entirely

Indian classical music has two foundational elements: raga (melody) and tala (rhythm). The raga—or raag—forms a melodic structure, while the tala measures the time cycle.

Unlike the chords and polyphonic compositions of Western Classical music, Indian music consists of permanent improvisations which are based on around six thousand ragas with a set of fixed rules.

Indian raga is built on a certain thaat mode which corresponds to the scales of Western music, for example, Bilawal thaat is equivalent to the major scale.

India has over a billion people and hundreds of dialects and languages spread across the seventh largest country in the world, but there is still an undeniable “sound” that makes Indian music unmistakable.

Indian music typically contains no harmony, can be completely improvised, and is rarely written down. So how do Indian musicians manage to play together? In this segment, we’ll learn about rhythmic patterns called taal, music unique to certain communities and even times of the year, and if deep-rooted musical traditions can continue as India undergoes fast-paced growth and modernization.

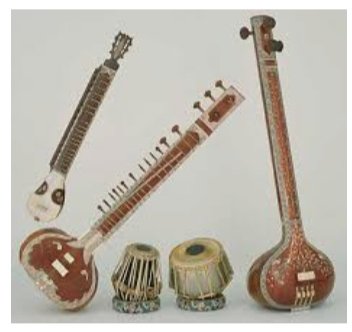

Hindustani instumental Music: Alongside Ravi Shankar himself,Nikhil BanerjeeandVilayat Khanare the best-known sitarists ofthe post-Independence years, responsible for innovationsin sitar design and exponents of a singingstyle of playing calledgayaki angwhich each seemsto have developed independently. Performers such as these have made Hindustani music a primary colour on the world music palette. For those that find the sitar’s incessant buzzing hard to take, thebansuri(bamboo flute) is a first-rate alternative introductory instrument, especially in the hands ofHariprasad Chaurasia,Ronu MajumdarorG.S. Sachdev. And so, too, is thesarod, an instrument which has a star equivalent to Ravi Shankar in the veteranAli Akbar Khan, a towering figure who provided the West with Hindustani music’s first major concert recitals and first long-playing record.

Karnatic: (Carnatic, Karnatak) music was once the musical language of the entire subcontinent, grounded in Hinduism and boasting a history and mythology thousands of years old as the articulation of Dravidian culture.Its tenets, once passed on only orally, were codified in Vedic literature between 4000 and 1000 BC, long before Western classical music was even in its infancy. One of the four main Vedic texts, theSama Veda, is the basis for all that followed. The music and the faith which inspired it have remained inseparable. Visitors to the vast temples of south India are much more likely to encounter music than they would be in the north. It’s usually the piercing sound of thenagaswaram(shawm) and thetavil(barrel drum). More thanlikely it accompanies flaming torches and a ceremonialprocession of the temple deity.

Vocal Music: More than any other classical genre,dhrupadis regarded as a sacred art – an act of devotionand meditation rather than entertainment. It isan ancient and austere form which ranks as theHindustani system’s oldest vocal music genre stillperformed. Traditionally, dhrupad is performed only by men, accompanied bytanpuraand thepakhawaj barrel drum. Nowadays it is most often set in atalaof twelve beats calledchautal. A dhrupad lyric (usually in a medieval literary form of Hindi called Braj Bhasha) may be pure panegyric, praising a Hindu deity or local royalty, or it may dwell on noble or heroic themes. The twist is that this most Hindu of vocal genres is dominated by Muslims.

Thebhajanis the most popular form of Hindu devotional composition in north India. Lyrically, bhajans eulogize a particular deity and frequently retell episodes from the Hindu scriptures. In the South, bhajans tend to retain their original Hindustani raga but are set in Karnatic talas, as the Karnatic violinistV.V. Subrahmanyam’s exquisite recordings for the Gramophone Company of India show.

Folk Music in India is often described asdesi(ordeshi), meaning “of the country”, to distinguish it from art music, known asmarga(meaning “chaste” and, by extension, classical). Desi, a catchall term, also embraces folk theatre and popular music of many colours. While there is extraordinary folk music to be found all over India, there are three areas where it is particularly rich and easy to access as a visitor – Rajasthan, Kerala and Bengal, where the Bauls are the inspirational music providers. Rajasthani groups and Baul musicians are popular performers on the world music circuit.

The harvest is celebrated in every culture and in the Punjab it gave rise tobhangra, a folk dance which, in its British commercial form, has transmogrified into a form of Asian pop. Following on from the crossover success of bhangra,dandiya, a new folk-based genre, has emerged as a new phenomenon with a club-based following in India.

Film music: Bollywood Indianfilms often succeed because of their songs. Stars get stereotyped and rarely find roles outside, say, romantic lead, swashbuckler, comic light relief, baddie and so on. What’s more, these highly paid actors and actresses lip-synch to pre-recorded songs sung by vocal superstars such as Lata Mangeshkar andS.P. Balasurahmaniam, off-camera. After these superstars,Kavita Krishnamurthy,Alka YagnikandUdit Narayanare among the crowd-pulling names.

The leading trio which dominated the Hindi cinema for over thirty years wereMukesh(1923–76),Mohammed Rafi(1924–80) and Lata Mangeshkar (b. 1929). Dreamy strings provide the lush backings, an Indianized account of Hollywood strings, but bursting with touches that could only come from the subcontinent. The Los Angeles of the Indian film industry isMumbai, the decolonialized Bombay, hence the common shorthandBollywood– a film industry in-joke that stuck and went international.

East- West Fusions All stories are approximations and East–West fusions didn’t entirely begin with The Beatles. India exerted influences on Western classical music over the course of the entire twentieth century. The ideas that India planted ranged from the philosophical and religious to the organizational (melody and rhythmicality) and organological (the use of Indian instruments).

You must be logged in to post a comment.