By Rabindranath Tagore

“O master poet, I have sat down at thy feet. Only let me make my life simple and straight, like a flute of reed for thee to fill with music.”— Rabindranath Tagore

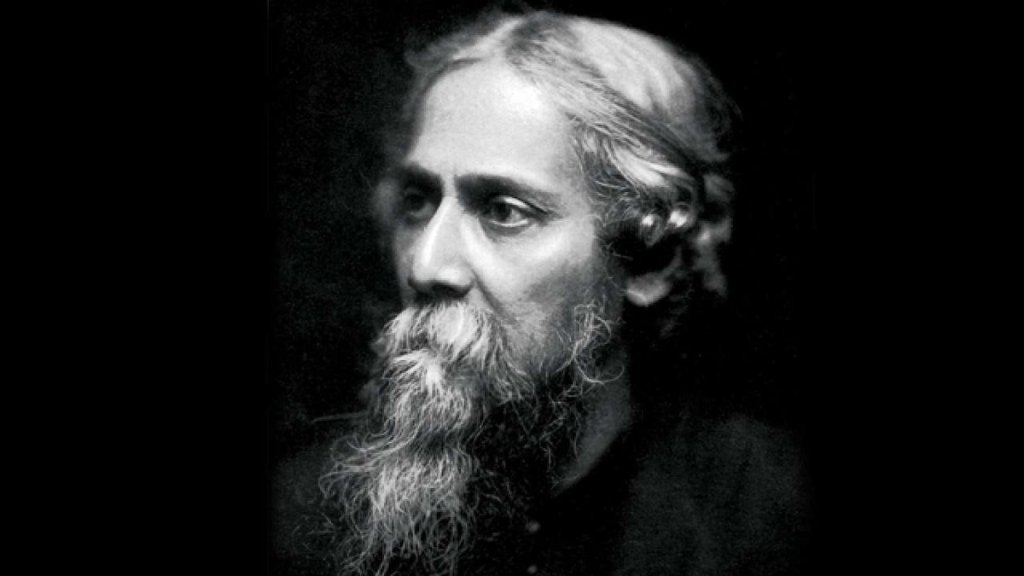

ABOUT THE POET

Rabindranath Tagore was born in Calcutta on May 6, 1861. Tagore came from a wealthy Bengali family. He was educated privately and went to England in 1877 to study law but soon returned to India or a time he managed his father’s estates and became involved with the Indian nationalist movement writing propaganda. His characteristic later style combines natural descriptions with religious and philosophical descriptions. He is our greatest poet after Kalidas. His Gitanjali published in 1912, won the Nobel Prize.

Tagore wrote a large number of lyrics in Bengali and translated some of them himself into English. He also wrote novels, short Stories and plays. His best-known novels and poetry include The Gardener, The Crescent Man, Songs of Kabir. ‘Chitra’ etc.

Tagore was a messenger of India who showed Europe some of the beauty and greatness of our ancient land. He brought great glory to his motherland.

THE POEM

‘Flute-music’ is the story of a lower middle-class clerk who lives an abject poverty. He lives in a dingy room on the ground floor of two Storeyed houses. He barely manages to exist on his meagre salary and feels suffocated and nauseated by the darkness and foul smell of the alley. But one evening the music from the flute of one of the Residents makes him dream and he feels uplifted like a king. He dreams of marrying the girl of his dreams and forgets his destitute life.

The poem gives an account of the poverty-stricken existence of a middle-class clerk.

In Kinu, the milkman’s street, on the ground floor room of a double storeyed house lives a poor clerk. The windows of the room have bars, the walls are old and peeling, falling to dust in most places or damp with moisture. On the door of the room is pasted Picture of Lord Ganesh, the god who brings success and prosperity, taken from a roll of cloth. Apart from the clerk there is another inhabitant of the room who lives without paying any rent, it is a lizard. But there is a difference between the lizard and the clerk, unlike him the lizard never goes hungry. The clerk gets a salary of twenty-five rupees a month as a junior clerk in a trading office. The Datta’s give him food for giving tuition to their son. In the evening he goes to Sealdah station to save the cost of electricity in his room and to while away time. Engine’s puff, whistles shriek, coolies shout, passengers hurry past. He stays there till past ten ‘o clock and then goes to sleep in his dark, silent and lonely room.

In a village, situated on the banks of the Dhalesvari river, his aunt’s family resides. He was to marry her brother-in-law’s daughter. The moment was lucky for her, no doubt about that, as he ran away. The girl was saved from marrying him, a poor man and he was saved from her. She did not come as his wife to the room but he was always thinking of her: dressed in a Dacca sari, with the red vermilion on her forehead showing her marital status.

It was raining heavily. His cost of travelling by tram mounts. But still his pay is deducted for reaching office late. In the street are strewn mango peels and stones, pulp of jack-fruit, rotting fish-gills, dead kittens and all kinds of other rubbish. Like his fast-diminishing salary his umbrella is also full of holes. His office clothes are wet and water oozes out like a religious man who has bathed for his prayers. The damp dinginess of monsoon prevails in his room, like an animal that has been trapped, still and shocked. Day and night the clerk feels helpless and bound on to a world which is only partly alive.

At the street corner lives Kanta babu-a man with long hair which has been carefully parted, large eyes and tastes which have been carefully pampered. He regards himself as a good musician who is skilled at playing the cornet: its sound can be heard at intervals, wafting on the vile-smell of the street it is heard sometimes in the middle of the night and sometimes at dawn, sometimes it can be heard in the afternoon when the sun shines brightly and the shadows are also not dark. However, on that particular evening Kanta babu starts playing the notes of Sindhu-Baroya raag on his instrument. The whole sky resounds with the soulful music playing the notes of the pain of separation. At that very moment the filthy street is no longer a reality, as false and dirty as the senseless talk of a drunk man, and the clerk also forgets his reality and feels at par with the Emperor Akbar. His torn umbrella takes the form of an emperor’s royal parasol and his soul rises along with royalty towards the same heaven. He no longer feels humble, the music uplifts him as if he were a king.

The music is what is true, a reality where, in the eternal evening he visualises his wedding, the waters of the Dhalesvari river flow its banks shaded by the leafy tamal trees and the girl waits for him in the courtyard of her house, wearing a Dacca sari, with the red mark of vermillion on her forehead.

You must be logged in to post a comment.