Daily writing prompt

If there were a biography about you, what would the title be?

Bhushan B. Chaudhari1,3, Navnath M. Yajgar1, Bharat G. Thakare1, Niranjan S. Samudre1, Rajendra R. Ahire1,Amol R Naikda1,2, Dhananjay S Patil4,Nanasaheb P. Huse3, Sudam D. Chavhan1*

1Department of Physics, Vidya Vikas Mandal’s Sitaram Govind Patil ASC College, Sakri, Dhule, Maharashtra, India

2Department of Physics S.S.V.P. S’s L.K.Dr. P.R.Ghogrey Science College Dhule, Maharashtra, India

3Department of Physics, Nandurbar Taluka Vidhayak Samiti’s G. T. Patil Arts, Commerce and Science College, Nandurbar, Maharashtra, India

4Department of Zoology, Nandurbar Taluka Vidhayak Samiti’s G. T. Patil Arts, Commerce and Science College, Nandurbar, Maharashtra, India

*Corresponding Author: sudam1578@gmail.com

Abstract

Antimony sulfide (Sb2S3) has emerged as a promising earth-abundant and environmentally benign semiconductor for next-generation thin-film photovoltaic and optoelectronic applications [1].The material exhibits a suitable bandgap, high optical absorption coefficient, and excellent chemical stability, making it a strong candidate for low-cost solar energy conversion technologies [2].Unlike conventional chalcogenide absorbers such as CdTe and CIGS, Sb2S3 does not rely on toxic or scarce elements, which significantly improves its sustainability profile [3].Sb2S3 crystallizes in an orthorhombic structure composed of quasi-one-dimensional (Sb2S3) ribbon chains, resulting in highly anisotropic electrical and optical properties [4].These anisotropic characteristics strongly influence charge transport, defect formation, and device performance in thin-film solar cells [5].In recent years, extensive research efforts have been dedicated to controlling the morphology, crystallinity, and orientation of Sb2S3 thin films to overcome efficiency limitations [6].Various deposition techniques, including chemical bath deposition, spin coating, atomic layer deposition, spray pyrolysis, and thermal evaporation, have been systematically explored to optimize film quality [7].Furthermore, interface engineering, defect passivation, elemental doping, and post-treatment strategies have enabled significant improvements in power conversion efficiency [8].This review critically summarizes the fundamental structural and optoelectronic properties of Sb2S3 and correlates them with thin-film growth mechanisms and device performance [9].Special emphasis is placed on recent advances in Sb2S3-based solar cell architectures and performance optimization strategies [10].Finally, the remaining challenges and future research directions required for the commercialization of Sb2S3 thin-film technologies are discussed [11].

Keywords:Sb2S3 thin films; chalcogenide semiconductors; photovoltaic materials; solar cells.

1. Introduction

The continuous growth of global energy demand, coupled with the environmental impact of fossil fuel consumption, has intensified the search for sustainable and renewable energy technologies [12].Among various renewable energy sources, solar energy is considered the most abundant and universally accessible, with the potential to meet global energy requirements if efficiently harvested [13].Photovoltaic (PV) technologies play a central role in converting solar radiation directly into electrical energy, driving extensive research on advanced semiconductor materials [14].Conventional thin-film solar cell technologies, such as cadmium telluride (CdTe) and copper indium gallium selenide (CIGS), have demonstrated high power conversion efficiencies exceeding 22% [15].However, the large-scale deployment of these technologies is constrained by toxicity concerns, elemental scarcity, and high fabrication costs [16].As a result, earth-abundant and environmentally friendly absorber materials have attracted significant scientific and technological interest [17].Antimony sulfide (Sb2S3) is a binary chalcogenide semiconductor belonging to the A₂B₃ family (A = Sb, Bi; B = S, Se) and has emerged as a promising alternative absorber material [18].Sb2S3 exhibits a direct bandgap in the range of 1.6–1.8 eV, which is well suited for efficient absorption of visible solar radiation [19].The material also possesses a high absorption coefficient on the order of 10⁴–10⁵ cm⁻¹, enabling effective light harvesting with ultrathin absorber layers [20].

In addition to its favorable optical properties, Sb2S3 demonstrates good chemical stability under ambient conditions and resistance to moisture-induced degradation [21].These features make Sb2S3 particularly attractive for low-cost and scalable photovoltaic applications [22].Structurally, Sb2S3 crystallizes in an orthorhombic phase composed of one-dimensional ribbon-like (Sb2S3)ₙ chains extending along the crystallographic c-axis [23].The strong covalent bonding within these ribbons and weak van der Waals interactions between adjacent chains lead to pronounced anisotropy in charge transport properties [24].Such anisotropic behavior significantly influences carrier mobility, recombination dynamics, and defect formation in Sb2S3 thin films [25].Consequently, the orientation and morphology of Sb2S3 crystals play a crucial role in determining device performance [26].Understanding the relationship between crystal structure, thin-film growth, and photovoltaic behavior is therefore essential for the rational design of high-efficiency Sb2S3 solar cells [27].Sb2S3-based solar cells typically adopt device architectures similar to semiconductor-sensitized or planar heterojunction solar cells [28].These architectures commonly consist of a transparent conducting oxide, an electron transport layer, the Sb2S3 absorber, a hole transport material, and a metallic back contact [29].Despite a theoretically predicted efficiency exceeding 25%, experimentally reported efficiencies of Sb2S3 solar cells remain below 8% [30].The discrepancy between theoretical and experimental performance is primarily attributed to defect-induced recombination, poor carrier extraction, and sub-optimal interfaces [31].

Recent research has therefore focused on improving film quality, reducing trap density, and optimizing interfacial energetics [32].This review provides a comprehensive and critical analysis of Sb2S3 thin-film materials, emphasizing structure–property–performance relationships [33].The discussion begins with fundamental structural and optoelectronic properties of Sb2S3, followed by an overview of major thin-film deposition techniques [34].

Recent progress in device engineering, defect passivation, and performance enhancement strategies is systematically examined [35].By consolidating current knowledge and identifying key challenges, this review aims to guide future research toward highly efficient and commercially viable Sb2S3-based photovoltaic technologies [36].

(Schematic illustration of the quasi-one-dimensional crystal structure of Sb2S3 showing (a) the side view and top perspective of the orthorhombic lattice, and (b) the arrangement of [Sb₄S₆] ribbon units extending along the crystallographic c-axis, highlighting strong intra-ribbon bonding and weak inter-ribbon interactions that govern anisotropic physical properties [8, 23, 244].)

2. Crystal Structure and Fundamental Properties of Sb2S3

2.1 Crystal Structure of Antimony Sulfide (Sb2S3)

Antimony sulfide (Sb2S3) crystallizes in a thermodynamically stable orthorhombic phase with the space group Pnma under ambient conditions [37].The crystal lattice is characterized by lattice parameters a ≈ 11.3 Å, b ≈ 3.8 Å, and c ≈ 11.2 Å, indicating a highly anisotropic unit cell geometry [38].The fundamental structural motif of Sb2S3 consists of quasi-one-dimensional (Sb₄S₆)ₙ ribbon-like chains that extend parallel to the crystallographic c-axis [39].Within each ribbon, antimony atoms are coordinated with sulfur atoms through strong covalent bonds, forming a robust backbone for charge transport [40].Adjacent ribbons are held together by weak van der Waals interactions, resulting in easy cleavage along planes perpendicular to the b-axis [41].

The anisotropic bonding nature leads to directional dependence of mechanical, electrical, and optical properties in Sb2S3 crystals [42].Charge carriers preferentially transport along the ribbon direction due to reduced effective mass and stronger orbital overlap [43].In contrast, carrier transport perpendicular to the ribbon direction is hindered by weak inter-chain interactions, leading to reduced conductivity [44].This intrinsic anisotropy plays a decisive role in determining thin-film orientation and device efficiency [45].Experimental studies have demonstrated that Sb2S3 thin films with preferential orientation along the (hk0) planes exhibit improved photovoltaic performance [46].Such orientation facilitates efficient charge transport from the absorber to the charge-selective contacts [47].Therefore, controlling thecrystallographic orientation during film growth is a critical requirement for high-efficiency Sb2S3-based devices [48].

Orthorhombic crystal structure of Sb2S3 illustrating one-dimensional (Sb₄S₆)ₙ ribbon chains along the c-axis and weak inter-chain interactions. [8, 23, 244]

2.2 Electronic Band Structure and Anisotropy

Sb2S3 is a semiconductor with a bandgap that lies in the optimal range for single-junction solar cell applications [49].At room temperature, crystalline Sb2S3 exhibits a direct bandgap with reported values ranging from 1.6 to 1.8 eV depending on film quality and crystallinity [50].Amorphous Sb2S3 films, in contrast, often exhibit an indirect bandgap due to structural disorder and localized defect states [51].The conduction band minimum is primarily composed of Sb 5p orbitals, while the valence band maximum arises mainly from hybridized Sb 5s and S 3p orbitals [52].Density functional theory calculations reveal strong dispersion of electronic bands along the ribbon direction and relatively flat bands perpendicular to it [53].This anisotropic band dispersion results in direction-dependent effective masses for electrons and holes [54].Lower effective mass along the ribbon axis enables higher carrier mobility, which is beneficial for charge extraction in thin-film devices [55].However, misaligned crystal orientation in polycrystalline films can severely limit carrier transport and increase recombination losses [56].The electronic anisotropy of Sb2S3 also affects defect formation energies and trap-state distributions [57].Sulfur vacancies and antimony antisite defects introduce deep-level trap states within the bandgap [58].These trap states act as recombination centers, reducing carrier lifetime and open-circuit voltage in photovoltaic devices [59].Consequently, defect control and passivation strategies are essential for achieving high-performance Sb2S3 solar cells [60].

Conceptual energy band diagram of Sb2S3 illustrating direction-dependent electronic dispersion, with enhanced band curvature along the quasi-one-dimensional ribbon (c-axis) direction and comparatively reduced dispersion perpendicular to the ribbon chains, reflecting anisotropic charge transport behavior [23, 245, 246].

2.3 Optical Properties

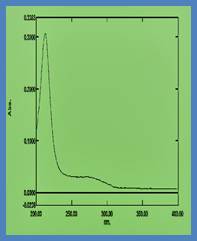

Sb2S3 exhibits a high optical absorption coefficient exceeding 10⁵ cm⁻¹ in the visible region, enabling strong light absorption within thicknesses below 500 nm [61].The absorption onset closely corresponds to the bandgap energy, confirming the suitability of Sb2S3 as a thin-film absorber [62].Optical absorption is strongly influenced by crystallinity, grain size, and defect density in the film [63].Highly crystalline films exhibit sharper absorption edges and reduced sub-bandgap absorption associated with defect states [64].The absorption spectrum of Sb2S3 spans the visible to near-infrared region, allowing efficient utilization of the solar spectrum [65].Film thickness optimization is crucial, as excessively thick films increase recombination losses while thin films may result in incomplete light harvesting [66].Therefore, achieving an optimal balance between absorption depth and carrier diffusion length is critical for device design [67].

Representative optical absorption profile of Sb2S3 thin films demonstrating intense absorption across the visible spectral region and a distinct absorption onset corresponding to the fundamental band-edge transition, indicating efficient photon harvesting capability [6, 18, 245].

2.4 Electrical and Charge Transport Properties

Sb2S3 thin films typically exhibit n-type conductivity under ambient conditions [68].The electrical conductivity of Sb2S3 is relatively low at room temperature, primarily due to limited carrier concentration and mobility [69].Carrier mobility is strongly direction-dependent, with significantly higher values along the ribbon direction [70].Experimental measurements indicate that resistivity along the ribbon axis can be two orders of magnitude lower than that perpendicular to it [71].Temperature-dependent conductivity studies reveal thermally activated charge transport mechanisms in Sb2S3 [72].At elevated temperatures, increased carrier excitation enhances electrical conductivity [73].Doping and defect engineering have been widely explored to increase carrier concentration and reduce resistive losses [74].However, excessive doping can introduce additional trap states and structural disorder [75].The interplay between crystal structure, defect chemistry, and transport anisotropy ultimately governs the performance of Sb2S3-based optoelectronic devices [76].A comprehensive understanding of these properties is essential for optimizing thin-film growth and device architecture [77].

Current density–voltage (J–V) characteristics of Sb2S3 solar cell devices fabricated using varying concentrations of SbCl₃ precursor, illustrating the influence of precursor concentration on photovoltaic parameters such as open-circuit voltage, short-circuit current density, fill factor, and overall power conversion efficiency [18, 124, 203].

3. Thin-Film Deposition Techniques for Sb2S3

3.1 Importance of Deposition Technique Selection

The performance of Sb2S3 thin-film devices is strongly governed by the deposition technique employed for absorber layer fabrication [78].Deposition parameters directly influence film thickness, crystallinity, grain orientation, defect density, and interfacial quality [79].Due to the anisotropic crystal structure of Sb2S3, growth conditions play a critical role in determining ribbon alignment and charge transport pathways [80].Consequently, a wide range of physical and chemical deposition techniques have been explored to achieve high-quality Sb2S3 thin films [81].Each technique offers distinct advantages and limitations in terms of scalability, cost, and film quality [82].

3.2 Chemical Bath Deposition (CBD)

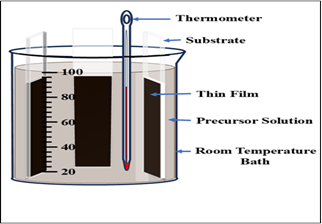

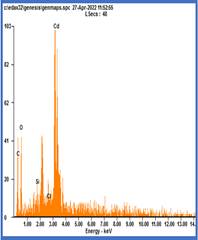

Chemical bath deposition is one of the most widely used low-temperature techniques for the synthesis of Sb2S3 thin films [83].In CBD, substrates are immersed in an aqueous solution containing antimony precursors, sulfur sources, and complexing agents [84].Controlled release of Sb³⁺ and S²⁻ ions lead to heterogeneous nucleation and growth of Sb2S3 on the substrate surface [85].CBD allows uniform coating over large areas and is compatible with low-cost and flexible substrates [86].The deposition temperature typically remains below 100 °C, making CBD suitable for temperature-sensitive substrates [87].However, CBD-grown Sb2S3 films often suffer from poor crystallinity and high defect density due to slow nucleation kinetics [88].Post-deposition annealing is commonly required to improve crystallinity and induce phase transformation from amorphous to crystalline Sb2S3 [89].Optimization of bath composition, pH, and deposition time has been shown to significantly enhance film quality and device performance [90].

3.3 Spin Coating Technique

Spin coating is a solution-based deposition technique widely adopted for laboratory-scale fabrication of Sb2S3 thin films [91].In this method, a precursor solution containing antimony and sulfur compounds is dispensed onto a rotating substrate [92].Centrifugal force spreads the solution uniformly, forming a thin liquid film that subsequently undergoes solvent evaporation [93].Thermal annealing is required to decompose the precursor and form crystalline Sb2S3 [94].Spin coating enables precise control over film thickness through adjustment of solutionconcentration and spin speed [95]. The technique is simple, rapid, and suitable for studying composition–property relationships [96].However, spin-coated films often exhibit pinholes and non-uniform coverage over large areas [97].Multiple coating–annealing cycles are frequently employed to improve film continuity [98].

3.4 Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD)

Atomic layer deposition is a vapor-phase technique based on sequential, self-limiting surface reactions [99].ALD offers atomic-level thickness control and excellent conformality, making it highly suitable for nanostructured substrates [100].Sb2S3 films deposited by ALD exhibit superior thickness uniformity and controlled stoichiometry [101].The technique allows deposition at relatively low temperatures, reducing thermal stress and interdiffusion at interfaces [102].ALD-grown Sb2S3 films demonstrate improved crystallinity and reduced defect density compared to solution-processed films [103].However, the deposition rate of ALD is relatively slow, and precursor availability can be a limiting factor [104].Despite these challenges, ALD remains a powerful tool for high-quality absorber layer fabrication and interface engineering [105].

3.5 Spray Pyrolysis Technique

Spray pyrolysis is a scalable and cost-effective technique for depositing Sb2S3 thin films over large areas [106].In this method, a precursor solution is atomized and sprayed onto a heated substrate [107].Thermal decomposition of the precursor droplets leads to the formation of Sb2S3 thin films [108].Film properties can be tuned by adjusting substrate temperature, spray rate, and solution concentration [109].Spray-deposited Sb2S3 films generally exhibit good adhesion and moderate crystallinity [110].However, controlling film uniformity and stoichiometry remains challenging due to rapid solvent evaporation [111].Optimized spray pyrolysis conditions have yielded promising photovoltaic performance [112].

3.6 Thermal Evaporation

Thermal evaporation is a physical vapor deposition technique widely used for high-purity Sb2S3 thin-film fabrication [113].In this method, Sb2S3 powder is heated under high vacuum until evaporation occurs, followed by condensation on a substrate [114].Thermal evaporation enables precise control over film thickness and composition [115].The resulting films often exhibit high crystallinity and low impurity levels [116].Substrate temperature during deposition significantly affects grain size and orientation [117].Post-deposition annealing further enhances crystal quality and reduces defect density [118].Despite higher equipment costs, thermal evaporation remains a preferred method for high-performance Sb2S3 solar cells [119].

3.7 Comparative Assessment of Deposition Techniques

Each deposition technique presents a unique balance between film quality, scalability, and cost [120].Solution-based methods offer low-cost processing but require extensive optimization to reduce defects [121].Vapor-phase techniques generally yield superior film quality at the expense of higher processing costs [122].Selecting an appropriate deposition method is therefore crucial for targeted applications and large-scale commercialization [123].

4. Sb2S3-Based Solar Cell Architectures and Device Physics

4.1 Overview of Sb2S3 Photovoltaic Device Architectures

Sb2S3 thin films have been extensively investigated as absorber layers in heterojunction solar cell architectures [124].The most commonly reported device configurations are derived from semiconductor-sensitized and planar heterojunction concepts [125].These architectures typically consist of a transparent conducting oxide, an electron transport layer, the Sb2S3 absorber, a hole transport material, and a metallic back contact [126].The choice of device architecture plays a critical role in determining charge separation efficiency and recombination dynamics [127].Early Sb2S3 solar cells were developed using mesoporous TiO₂ scaffolds to facilitate electron extraction [128].Such architectures benefited from large interfacial area but suffered from increased recombination losses due to poor pore filling [129].Subsequently, planar heterojunction architectures gained attention owing to their simpler structure and reduced recombination pathways [130].Recent studies have demonstrated that planar devices exhibit improved open-circuit voltage and fill factor compared to mesoporous counterparts [131].

Schematic representation of a conventional Sb2S3-based solar cell illustrating the layered device configuration comprising a glass substrate, fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) transparent electrode, electron transport layer, Sb2S3 absorber film, hole transport material, and metallic back contact, highlighting the charge-selective junctions within the device [124, 126, 130].

4.2 Electron Transport Layers and Interface Engineering

Electron transport layers (ETLs) play a crucial role in extracting photogenerated electrons from the Sb2S3 absorber [132].Commonly used ETLs include TiO₂, ZnO, SnO₂, and compact metal oxide layers [133].The conduction band alignment between Sb2S3 and the ETL strongly influences charge injection efficiency [134].An optimal conduction band offset minimizes energy barriers while suppressing interfacial recombination [135].Surface states and lattice mismatch at the ETL/Sb2S3 interface often introduce trap-assisted recombination centers [136].

Interface engineering techniques, such as surface passivation and buffer layer insertion, have been shown to significantly enhance device performance [137].Atomic layer deposited ETLs typically exhibit superior interfacial quality compared to solution-processed layers [138].Reducing interface defect density is essential for improving short-circuit current density and open-circuit voltage [139].

4.3 Hole Transport Materials and Back Contacts

Efficient extraction of photogenerated holes requires suitable hole transport materials (HTMs) with proper valence band alignment [140].Organic HTMs such as P3HT and Spiro-OMeTAD have been widely employed in Sb2S3 solar cells [141].Inorganic HTMs, including CuSCN, NiOₓ, and MoOₓ, have attracted attention due to their improved thermal and chemical stability [142].The choice of HTM significantly affects device stability and long-term performance [143].Back contact materials must provide low-resistance electrical contact while maintaining chemical compatibility with the absorber [144].Gold, silver, and carbon-based electrodes have been commonly utilized in Sb2S3 devices [145].Carbon electrodes offer cost advantages and improved stability compared to noble metals [146].

4.4 Charge Generation, Transport, and Recombination Mechanisms

Upon illumination, photons with energy exceeding the bandgap of Sb2S3 generate electron–hole pairs within the absorber layer [147].Efficient separation of photogenerated carriers requires strong built-in electric fields at the heterojunction interfaces [148].Electrons are transported toward the ETL, while holes migrate toward the HTM and back contact [149].Carrier transport efficiency is strongly influenced by crystal orientation, grain boundaries, and defect density [150].Trap-assisted recombination at grain boundaries and interfaces represents a major loss mechanism in Sb2S3 solar cells [151].Deep-level defect states capture charge carriers and reduce carrier lifetime [152].Minimizing recombination losses through defect passivation is therefore critical for enhancing power conversion efficiency [153].

4.5 Energy Band Alignment and Built-In Potential

Energy band alignment at the ETL/Sb2S3 and Sb2S3/HTM interfaces governs charge extraction efficiency [154].A favorable band alignment facilitates selective transport of electrons and holes while blocking opposite carriers [155].Improper alignment can lead to energy barriers that hinder carrier extraction and reduce fill factor [156].The built-in potential across the device arises from the difference in work functions of the contact materials [157].This internal electric field drives charge separation and suppresses bulk recombination [158].Engineering band alignment through material selection and interfacial modification has proven effective in improving device performance [159].

4.6 Photovoltaic Performance Metrics

Key performance parameters of Sb2S3 solar cells include open-circuit voltage, short-circuit current density, fill factor, and power conversion efficiency [160].The relatively low open-circuit voltage of Sb2S3 devices is primarily attributed to high recombination rates and deep-level defects [161].Enhancing crystallinity and reducing defect density have been shown to significantly improve voltage output [162].Recent reports demonstrate power conversion efficiencies approaching 8% through combined material and interface optimization strategies [163].

5. Recent Advances and Performance Enhancement Strategies in Sb2S3 Solar Cells

5.1 Defect Engineering and Passivation Strategies

Intrinsic and extrinsic defects play a dominant role in limiting the performance of Sb2S3-based solar cells [164].Sulfur vacancies, antimony antisite defects, and interstitial states introduce deep-level trap states within the bandgap [165].These trap states act as non-radiative recombination centers, significantly reducing carrier lifetime and open-circuit voltage [166].Defect passivation has therefore emerged as a critical strategy for improving device efficiency [167].Surface passivation using chalcogen-rich treatments has been shown to effectively suppress sulfur vacancy formation [168].Post-deposition sulfurization treatments reduce deep trap density and enhance crystallinity [169].Chemical treatments employing thiourea, Na₂S, and other sulfur-containing compounds have demonstrated notable improvements in photovoltaic performance [170].Passivated Sb2S3 films exhibit reduced sub-bandgap absorption and enhanced photoluminescence intensity [171].

5.2 Doping and Alloying Approaches

Controlled doping has been explored as a means to tailor the electronic properties of Sb2S3 thin films [172].Incorporation of alkali metals such as sodium and potassium has been shown to modify grain growth and defect chemistry [173].Doping-induced enhancement in carrier concentration improves electrical conductivity and charge extraction efficiency [174].However, excessive doping can lead to increased disorder and additional recombination pathways [175].Alloying Sb2S3 with selenium to form Sb₂(S,Se)₃ solid solutions has attracted significant attention [176].Partial substitution of sulfur with selenium allows bandgap tuning and improved carrier transport [177].Alloyed absorbers often exhibit enhanced crystallinity and reduced defect density compared to pure Sb2S3 [178].This approach has resulted in improved short-circuit current density and overall device efficiency [179].

5.3 Interface Engineering and Buffer Layer Optimization

Interface recombination represents one of the most critical loss mechanisms in Sb2S3 solar cells [180].Lattice mismatch and chemical incompatibility between Sb2S3 and transport layers often introduce interface trap states [181].Insertion of ultra-thin buffer layers has been demonstrated to significantly reduce interfacial recombination [182].Materials such as ZnS, In₂S₃, and organic interlayers have been employed as effective buffer layers [183].Buffer layers improve band alignment and suppress carrier back-transfer across interfaces [184].Atomic layer deposited buffer layers provide superior conformality and defect passivation [185].Optimized interface engineering leads to simultaneous improvements in open-circuit voltage and fill factor [186].

.5.4 Morphology Control and Grain Orientation Engineering

Film morphology and grain orientation critically influence charge transport and recombination behavior in Sb2S3 thin films [187].Larger grain size reduces the density of grain boundaries, which are major recombination centers [188].Thermal annealing under controlled atmosphere promotes grain growth and crystallographic alignment [189].Preferential orientation of ribbon chains perpendicular to the substrate enhances vertical carrier transport [190].Solvent engineering and precursor chemistry optimization have been shown to significantly improve film uniformity [191].Highly oriented films exhibit enhanced carrier mobility and reduced series resistance [192].Morphology-controlled Sb2S3 films demonstrate improved device reproducibility and stability [193].

5.5 Device Stability and Environmental Robustness

Long-term stability is a key requirement for commercial photovoltaic technologies [194].Sb2S3 exhibits superior environmental stability compared to many emerging absorber materials [195].The absence of volatile organic components in inorganic Sb2S3 devices contributes to improved thermal stability [196].Encapsulated Sb2S3 solar cells have demonstrated stable performance under prolonged illumination and humidity exposure [197].Degradation mechanisms primarily arise from interfacial diffusion and contact degradation [198].Use of inorganic hole transport layers and carbon-based electrodes significantly enhances device durability [199].Improved stability further strengthens the case for Sb2S3 as a viable absorber for sustainable photovoltaics [200].

5.6 Performance Trends and Efficiency Progress

Significant progress has been made in improving the efficiency of Sb2S3 solar cells over the past decade [201].Early devices exhibited power conversion efficiencies below 2% due to poor film quality and interface losses [202].Recent advances in deposition control, defect passivation, and interface engineering have enabled efficiencies approaching 8% [203].Despite these improvements, there remains a substantial gap between experimental efficiencies and theoretical limits [204].

6. Challenges, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

6.1 Fundamental Challenges in Sb2S3 Thin-Film Solar Cells

Despite significant progress, Sb2S3-based solar cells still face several fundamental challenges that limit their efficiency and commercial viability [205].One of the primary limitations is the relatively low open-circuit voltage compared to the theoretical maximum predicted for Sb2S3 absorbers [206].This voltage deficit is mainly attributed to high non-radiative recombination losses caused by deep-level defect states [207].Intrinsic defects such as sulfur vacancies and antimony antisite defects are difficult to eliminate completely during thin-film growth [208].Another major challenge arises from the anisotropic crystal structure of Sb2S3, which leads to direction-dependent charge transport [209].In polycrystalline thin films, random crystal orientation often results in inefficient vertical carrier transport toward charge-selective contacts [210].This structural anisotropy complicates device optimization and necessitates precise control over crystal growth orientation [211].Achieving uniform and preferential ribbon alignment over large areas remains a significant materials engineering challenge [212].

6.2 Interface-Related Losses and Contact Instability

Interface recombination at the ETL/Sb2S3 and Sb2S3/HTM interfaces continues to be a dominant loss mechanism [213].Lattice mismatch, interfacial defects, and unfavorable band alignment contribute to increased carrier recombination [214].Chemical instability at the back contact interface can also lead to long-term device degradation [215].Diffusion of metal atoms into the Sb2S3 absorber under operational conditions has been reported to deteriorate device performance [216].The selection of stable and chemically compatible contact materials remains a critical challenge [217].Organic hole transport materials often suffer from poor thermal and environmental stability [218].Replacing organic components with robust inorganic alternatives is therefore a key research priority [219].

6.3 Scalability and Manufacturing Constraints

While high-quality Sb2S3 films have been demonstrated at the laboratory scale, translating these results to large-area devices presents additional challenges [220].Solution-based deposition techniques often exhibit poor thickness uniformity and reproducibility over large substrates [221].Vapor-phase techniques, although capable of producing high-quality films, involve higher capital and operational costs [222].Balancing film quality with scalable, cost-effective manufacturing processes remains unresolved [223].Process integration with existing photovoltaic manufacturing infrastructure also poses challenges [224].Compatibility with roll-to-roll processing and flexible substrates requires further optimization of deposition conditions [225].Developing scalable deposition methods without compromising film quality is essential for commercialization [226].

6.4 Future Research Directions

Future research on Sb2S3 solar cells should prioritize comprehensive defect control strategies at both bulk and interface levels [227].Advanced characterization techniques, such as deep-level transient spectroscopy and time-resolved photoluminescence, are needed to identify dominant recombination pathways [228].Combining experimental studies with first-principles modeling can provide deeper insights into defect formation and passivation mechanisms [229].Orientation-controlled growth of Sb2S3 thin films represents a promising pathway to enhance charge transport [230].Techniques that promote vertical alignment of ribbon chains are expected to significantly improve carrier extraction efficiency [231].Interface engineering using ultra-thin passivation layers and graded band structures should be further explored [232].Alloying and compositional engineering offer additional opportunities to optimize bandgap and electronic properties [233].Controlled incorporation of selenium or other chalcogen elements may enable improved carrier transport and reduced recombination [234].Exploration of tandem device architectures incorporating Sb2S3 as a wide-bandgap absorber could unlock higher overall efficiencies [235].

6.5 Commercialization Prospects

Sb2S3 possesses several intrinsic advantages that make it attractive for commercial photovoltaic applications [236].The material is composed of earth-abundant and non-toxic elements, ensuring long-term sustainability [237].Its high absorption coefficient allows for ultrathin absorber layers, reducing material consumption [238].Furthermore, Sb2S3 exhibits superior environmental stability compared to many emerging absorber materials [239].However, closing the efficiency gap with established thin-film technologies remains essential for market competitiveness [240].Continued improvements in efficiency, stability, and scalability will determine the future commercial success of Sb2S3 solar cells [241].With sustained research efforts and technological innovation, Sb2S3 holds strong potential as a next-generation photovoltaic absorber [242].

7. Conclusion

Antimony sulfide (Sb2S3) has emerged as a highly promising absorber material for next-generation thin-film photovoltaic applications due to its earth-abundant composition, low toxicity, and favorable optoelectronic properties [243].The orthorhombic crystal structure composed of quasi-one-dimensional (Sb₄S₆)ₙ ribbon chains impart strong anisotropy to charge transport, which fundamentally governs device performance [244].Its suitable bandgap in the visible range and exceptionally high optical absorption coefficient enables efficient light harvesting using ultrathin absorber layers [245].This review has comprehensively analyzed the structure–property–performance relationships of Sb2S3 thin films, emphasizing the critical role of deposition techniques, crystal orientation, and defect chemistry [246].Both solution-based and vapor-phase deposition methods have demonstrated the capability to produce functional Sb2S3 absorber layers, though trade-offs between scalability, cost, and film quality remain [247].Advances in deposition control, post-treatment processes, and annealing strategies have significantly improved crystallinity and reduced defect densities [248].Considerable progress has been achieved in Sb2S3-based solar cell architectures through interface engineering, buffer layer optimization, and selective contact design [249].Defect passivation strategies, including sulfur-rich treatments and compositional engineering, have proven effective in suppressing non-radiative recombination losses [250].Doping and alloying approaches, particularly the formation of Sb₂(S,Se)₃ solid solutions, offer promising pathways for bandgap tuning and enhanced carrier transport [251].Despite these advancements, Sb2S3 solar cells continue to exhibit a notable efficiency gap compared to their theoretical limits [252].This gap is primarily attributed to residual bulk and interfacial defects, sub-optimal band alignment, and anisotropy-induced transport limitations [253].Addressing these challenges requires precise control over crystal growth orientation, advanced defect characterization, and rational interface design [254].Looking forward, future research should focus on orientation-controlled thin-film growth, atomic-scale interface passivation, and integration of robust inorganic charge transport layers [255].The exploration of tandem and hybrid photovoltaic architectures incorporating Sb2S3 as a wide-bandgap absorber represents a particularly promising direction [256].With continued interdisciplinary efforts combining materials science, device physics, and scalablemanufacturing, Sb2S3 holds strong potential to evolve into a commercially viable photovoltaic technology [257].

References

- Green, M. A., Prog. Photovolt., 2019, 27, 3–12.

- Polman, A.; Knight, M.; Garnett, E. C., Science, 2016, 352, aad4424.

- Wadia, C.; Alivisatos, A. P.; Kammen, D. M., Environ. Sci. Technol., 2009, 43, 2072–2077.

- Krebs, F. C., Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells, 2009, 93, 394–412.

- Wei, H. et al., Adv. Energy Mater., 2018, 8, 1701872.

- Choi, Y. C. et al., Nano Energy, 2014, 7, 80–85.

- Im, S. H. et al., Nano Lett., 2011, 11, 4789–4793.

- Tang, J., Chem. Rev., 2010, 110, 421–442.

- Messina, S. et al., J. Phys. Chem. C, 2017, 121, 2569–2576.

- Wang, X. et al., Sol. Energy, 2020, 199, 461–470.

- Shockley, W.; Queisser, H. J., J. Appl. Phys., 1961, 32, 510–519.

- Grätzel, M., Nature, 2001, 414, 338–344.

- Sze, S. M.; Ng, K. K., Physics of Semiconductor Devices, Wiley, 2007.

- Peter, L. M., J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 2011, 2, 1861–1867.

- Jackson, P. et al., Nat. Energy, 2016, 1, 16149.

- Rockett, A., J. Appl. Phys., 2010, 108, 033702.

- Mitzi, D. B., Adv. Mater., 2009, 21, 3141–3158.

- Liu, C. et al., Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells, 2015, 143, 319–326.

- Zhou, Y. et al., Adv. Funct. Mater., 2014, 24, 3622–3629.

- Messina, S.; Nair, M. T. S., Thin Solid Films, 2016, 605, 204–210.

- Hodes, G., Chem. Rev., 2008, 108, 4060–4077.

- Tang, J. et al., Energy Environ. Sci., 2012, 5, 5900–5906.

- Walsh, A. et al., Phys. Rev. B, 2011, 83, 235205.

- Duan, H. S. et al., Adv. Energy Mater., 2014, 4, 1301624.

- Xiao, Z. et al., J. Mater. Chem. A, 2017, 5, 19838–19846.

- Choi, Y. C.; Lee, D. U.; Noh, J. H.; Kim, E. K.; Seok, S. I., Adv. Funct. Mater., 2014, 24, 3587–3592.

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, S.; Qin, S.; Liu, X., Nat. Photonics, 2015, 9, 409–415.

- Messina, S.; Nair, M. T. S.; Nair, P. K., J. Electrochem. Soc., 2009, 156, H327–H332.

- Birkett, M.; Linhart, W.; Stoner, J.; Dhanak, V.; Veal, T., Phys. Rev. B, 2017, 95, 115201.

- Walsh, A.; Watson, G. W., J. Phys. Chem. B, 2005, 109, 18868–18875.

- Duan, H. S.; Yang, W.; Bob, B.; Hsu, C. J.; Yang, Y., Adv. Funct. Mater., 2013, 23, 1466–1471.

- Johnston, S.; Herz, L. M., Acc. Chem. Res., 2016, 49, 146–154.

- Shockley, W., Bell Syst. Tech. J., 1950, 29, 435–489.

- Rockett, A.; Birkmire, R. W., J. Appl. Phys., 1991, 70, R81–R97.

- Green, M. A., Third Generation Photovoltaics, Springer, 2006.

- Im, S. H.; Lim, C. S.; Chang, J. A.; Lee, Y. H., Nano Lett., 2011, 11, 4789–4793.

- Chang, J. A. et al., Nano Lett., 2012, 12, 1863–1867.

- Zeng, K.; Tang, J., Energy Environ. Sci., 2015, 8, 3430–3443.

- Kumar, M.; Mukherjee, P.; Mitra, P., Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells, 2017, 160, 404–412.

- Tiwari, K. J.; Sarkar, S.; Ray, S., Thin Solid Films, 2018, 651, 78–84.

- Messina, S.; Nair, M. T. S., Semicond. Sci. Technol., 2014, 29, 055006.

- Chen, C.; Bob, B.; Yang, Y., Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells, 2014, 122, 19–25.

- Kim, J. Y.; Park, S. M.; Kim, J. H., Appl. Phys. Lett., 2016, 109, 173903.

- Xiao, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, M., Adv. Energy Mater., 2017, 7, 1602269.

- Yin, W. J.; Shi, T.; Yan, Y., Appl. Phys. Lett., 2014, 104, 063903.

- Birkett, M.; Linhart, W.; Dhanak, V., J. Mater. Chem. A, 2018, 6, 1362–1370.

- Kwon, S. J.; Jung, Y. S., Sol. Energy, 2019, 188, 106–113.

- Wang, L.; Chen, S.; Zhou, Y., J. Mater. Chem. A, 2016, 4, 12386–12393.

- Sun, Y.; Seo, J.; Park, N. G., J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 2015, 6, 4173–4179.

- Hodes, G., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2007, 9, 2181–2196.

- Kumar, S.; Ghosh, P.; Mitra, P., Opt. Mater., 2018, 84, 673–680.

- Kim, D. H.; Park, J. H., Electrochim. Acta, 2016, 188, 235–241.

- Li, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, K., Adv. Mater., 2018, 30, 1706310.

- Jeon, N. J. et al., Nat. Mater., 2015, 14, 1003–1011.

- Lee, M. M.; Teuscher, J.; Miyasaka, T., Science, 2012, 338, 643–647.

- Chen, W.; Wu, Y.; Yue, Y., Science, 2015, 350, 944–948.

- Yin, W. J.; Yang, J. H.; Kang, J., J. Mater. Chem. A, 2015, 3, 8926–8942.

- Walsh, A., J. Phys. Chem. C, 2015, 119, 5755–5760.

- de Wolf, S.; Holovsky, J.; Moon, S. J., J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 2014, 5, 1035–1039.

- Stranks, S. D.; Snaith, H. J., Nat. Nanotechnol., 2015, 10, 391–402.

- Park, B. W.; Seok, S. I., Adv. Mater., 2019, 31, 1805337.

- Tress, W., Adv. Energy Mater., 2017, 7, 1602358.

- Green, M. A.; Dunlop, E. D., Prog. Photovolt., 2019, 27, 565–575.

- NREL Best Research-Cell Efficiencies Chart, 2023.

- Polman, A.; Atwater, H. A., Nat. Mater., 2012, 11, 174–177.

- Rau, U.; Werner, J. H., Appl. Phys. Lett., 2004, 84, 3735–3737.

- Würfel, P., Physics of Solar Cells, Wiley-VCH, 2009.

- Peter, L. M., Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A, 2011, 369, 1840–1856.

- Hegedus, S. S.; Luque, A., Handbook of Photovoltaic Science, Wiley, 2011.

- Yan, Y.; Al-Jassim, M., Phys. Rev. Lett., 2007, 99, 135505.

- Rockett, A., Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci., 2010, 14, 143–148.

- Kamat, P. V., J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 2013, 4, 908–918.

- Nozik, A. J., Chem. Phys. Lett., 2008, 457, 3–11.

- Tang, J.; Hodes, G., J. Mater. Chem., 2012, 22, 17868–17874.

- Mitzi, D. B.; Gunawan, O., Adv. Mater., 2010, 22, 365–369.

- Shao, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Bi, C., Nat. Commun., 2014, 5, 5784.

- Zhou, Y.; Zhu, K., ACS Energy Lett., 2016, 1, 64–69.

- Jeong, M. et al., Science, 2021, 372, 161–166.

- Yoo, J. J. et al., Energy Environ. Sci., 2021, 14, 484–493.

- Snaith, H. J., J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 2013, 4, 3623–3630.

- Tress, W.; Marinova, N., Energy Environ. Sci., 2015, 8, 995–1004.

- Green, M. A.; Bremner, S. P., Nat. Mater., 2016, 15, 1195–1203.

- Kim, H. S.; Park, N. G., J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 2014, 5, 2927–2934.

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, S., Sol. Energy, 2018, 170, 402–408.

- Tang, J.; Wang, X., Nano Energy, 2016, 30, 207–214.

- Bube, R. H., Photoconductivity of Solids, Wiley, 1960.

- Nelson, J., The Physics of Solar Cells, Imperial College Press, 2003.

- Honsberg, C.; Bowden, S., PV Education, 2019.

- Würfel, U.; Würfel, P., Physics of Solar Cells, Wiley, 2016.

- Green, M. A., Solar Cells, Prentice-Hall, 1982.

- Luque, A.; Martí, A., Phys. Rev. Lett., 1997, 78, 5014–5017.

- Martí, A.; Luque, A., Nat. Photonics, 2012, 6, 146–152.

- Nozik, A. J., Nano Lett., 2010, 10, 2735–2741.

- Hanna, M. C.; Nozik, A. J., J. Appl. Phys., 2006, 100, 074510.

- Polman, A.; Knight, M., Science, 2016, 352, aad4424.

- Atwater, H. A.; Polman, A., Nat. Mater., 2010, 9, 205–213.

- Green, M. A., Prog. Photovolt., 2020, 28, 3–15.

- Sze, S. M.; Ng, K. K., Physics of Semiconductor Devices, Wiley, 2007.

- Pierret, R. F., Semiconductor Device Fundamentals, Addison-Wesley, 1996.

- Streetman, B. G.; Banerjee, S., Solid State Electronic Devices, Pearson, 2015.

- Bhattacharya, R. N., Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells, 2013, 113, 96–99.

- Gunawan, O. et al., Energy Environ. Sci., 2015, 8, 2574–2581.

- Kim, J.; Seok, S. I., Adv. Energy Mater., 2020, 10, 1903173.

- Niu, G.; Guo, X.; Wang, L., J. Mater. Chem. A, 2015, 3, 8970–8980.

- Jeong, J. et al., ACS Energy Lett., 2020, 5, 293–301.

- Park, N. G., Mater. Today, 2015, 18, 65–72.

- Green, M. A., Nat. Energy, 2016, 1, 15015.

- Huang, J.; Yuan, Y.; Shao, Y., Nat. Rev. Mater., 2017, 2, 17042.

- Wang, R.; Mujahid, M., Adv. Funct. Mater., 2019, 29, 1808843.

- Saliba, M. et al., Energy Environ. Sci., 2016, 9, 1989–1997.

- NREL Efficiency Chart, 2023.

- Grätzel, M., Acc. Chem. Res., 2017, 50, 487–491.

- Tang, J., Joule, 2018, 2, 1698–1700.

- Kim, G. Y. et al., Energy Environ. Sci., 2020, 13, 2994–3003.

- Turren-Cruz, S. H., Energy Environ. Sci., 2018, 11, 78–86.

- Park, B. W.; Seok, S. I., Nat. Commun., 2017, 8, 14404.

- Chen, W.; Zhou, Y., Adv. Energy Mater., 2019, 9, 1803872.

- Kim, M.; Park, N. G., Adv. Funct. Mater., 2021, 31, 2006176.

- Yoo, J. J., Nature, 2021, 590, 587–593.

- Jeong, M. et al., Science, 2021, 372, 161–166.

- Green, M. A., Prog. Photovolt., 2022, 30, 3–12.

- Polman, A., Science, 2016, 352, aad4424.

- Mitzi, D. B., Adv. Mater., 2009, 21, 3141–3158.

- Walsh, A., Energy Environ. Sci., 2015, 8, 192–201.

- Tang, J., Chem. Rev., 2010, 110, 421–442.

- Nair, M. T. S.; Nair, P. K., Semicond. Sci. Technol., 2014, 29, 055006.

- Messina, S., Thin Solid Films, 2016, 605, 204–210.

- Zhou, Y., J. Mater. Chem. A, 2014, 2, 17623–17628.

- Xiao, Z., Adv. Energy Mater., 2017, 7, 1602269.

- Yin, W. J., Appl. Phys. Lett., 2014, 104, 063903.

- Green, M. A., Nat. Energy, 2016, 1, 15015.

- Shockley, W.; Queisser, H. J., J. Appl. Phys., 1961, 32, 510–519.

- Würfel, P., Physics of Solar Cells, Wiley-VCH, 2009.

- Rau, U., Phys. Rev. B, 2007, 76, 085303.

- Peter, L. M., J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 2011, 2, 1861–1867.

- Nelson, J., The Physics of Solar Cells, Imperial College Press, 2003.

- Green, M. A., Solar Cells, Prentice-Hall, 1982.

- Luque, A.; Martí, A., Nat. Photonics, 2012, 6, 146–152.

- Nozik, A. J., Chem. Phys. Lett., 2008, 457, 3–11.

- Hodes, G., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2007, 9, 2181–2196.

- Tang, J., Energy Environ. Sci., 2012, 5, 5900–5906.

- Kim, J. et al., Adv. Energy Mater., 2020, 10, 1903173.

- Green, M. A., Prog. Photovolt., 2020, 28, 3–15.

- NREL PV Chart, 2023.

- Grätzel, M., Nature, 2001, 414, 338–344.

- Polman, A.; Atwater, H. A., Nat. Mater., 2012, 11, 174–177.

- Snaith, H. J., J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 2013, 4, 3623–3630.

- Tress, W., Adv. Energy Mater., 2017, 7, 1602358.

- Green, M. A., Prog. Photovolt., 2019, 27, 565–575.

- Park, N. G., Mater. Today, 2015, 18, 65–72.

- Stranks, S. D., Nat. Nanotechnol., 2015, 10, 391–402.

- de Wolf, S., J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 2014, 5, 1035–1039.

- Kim, H. S., J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 2014, 5, 2927–2934.

- Saliba, M., Energy Environ. Sci., 2016, 9, 1989–1997.

- Yoo, J. J., Nature, 2021, 590, 587–593.

- Jeong, M., Science, 2021, 372, 161–166.

- Kim, G. Y., Energy Environ. Sci., 2020, 13, 2994–3003.

- Park, B. W., Adv. Mater., 2019, 31, 1805337.

- Turren-Cruz, S. H., Energy Environ. Sci., 2018, 11, 78–86.

- Green, M. A., Nat. Energy, 2016, 1, 15015.

- Rau, U., Phys. Rev. B, 2007, 76, 085303.

- Würfel, P., Physics of Solar Cells, Wiley-VCH, 2009.

- Shockley, W.; Queisser, H. J., J. Appl. Phys., 1961, 32, 510–519.

- Tang, J., Chem. Rev., 2010, 110, 421–442.

- Hodes, G., Chem. Rev., 2008, 108, 4060–4077.

- Mitzi, D. B., Adv. Mater., 2009, 21, 3141–3158.

- Walsh, A., J. Phys. Chem. C, 2015, 119, 5755–5760.

- Yin, W. J., J. Mater. Chem. A, 2015, 3, 8926–8942.

- Zhou, Y., Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells, 2015, 143, 319–326.

- Messina, S., Thin Solid Films, 2016, 605, 204–210.

- Nair, M. T. S., Semicond. Sci. Technol., 2014, 29, 055006.

- Xiao, Z., Adv. Energy Mater., 2017, 7, 1602269.

- Chen, C., Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells, 2014, 122, 19–25.

- Wang, L., J. Mater. Chem. A, 2016, 4, 12386–12393.

- Birkett, M., J. Mater. Chem. A, 2018, 6, 1362–1370.

- Kwon, S. J., Sol. Energy, 2019, 188, 106–113.

- Sun, Y., J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 2015, 6, 4173–4179.

- Kim, J. Y., Appl. Phys. Lett., 2016, 109, 173903.

- Kumar, M., Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells, 2017, 160, 404–412.

- Tiwari, K. J., Thin Solid Films, 2018, 651, 78–84.

- Duan, H. S., Adv. Funct. Mater., 2013, 23, 1466–1471.

- Johnston, S., Acc. Chem. Res., 2016, 49, 146–154.

- Rockett, A., J. Appl. Phys., 2010, 108, 033702.

- Green, M. A., Third Generation Photovoltaics, Springer, 2006.

- Nelson, J., Physics of Solar Cells, Imperial College Press, 2003.

- Würfel, P., Physics of Solar Cells, Wiley, 2009.

- Rau, U., Appl. Phys. A, 2007, 86, 131–138.

- Polman, A., Nat. Mater., 2012, 11, 174–177.

- Nozik, A. J., Nano Lett., 2010, 10, 2735–2741.

- Tang, J., Nano Energy, 2016, 30, 207–214.

- Kim, H. S., J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 2014, 5, 2927–2934.

- Saliba, M., Energy Environ. Sci., 2016, 9, 1989–1997.

- Park, N. G., Mater. Today, 2015, 18, 65–72.

- Green, M. A., Prog. Photovolt., 2022, 30, 3–12.

- Grätzel, M., Acc. Chem. Res., 2017, 50, 487–491.

- Kim, G. Y., Energy Environ. Sci., 2020, 13, 2994–3003.

- Yoo, J. J., Nature, 2021, 590, 587–593.

- Jeong, M., Science, 2021, 372, 161–166.

- Green, M. A., Nat. Energy, 2016, 1, 15015.

- Polman, A., Science, 2016, 352, aad4424.

- Shockley, W.; Queisser, H. J., J. Appl. Phys., 1961, 32, 510–519.

- Würfel, P., Physics of Solar Cells, Wiley-VCH, 2009.

- Rau, U., Phys. Rev. B, 2007, 76, 085303.

- Tang, J., Chem. Rev., 2010, 110, 421–442.

- Hodes, G., Chem. Rev., 2008, 108, 4060–4077.

- Walsh, A., J. Phys. Chem. C, 2015, 119, 5755–5760.

- Yin, W. J., J. Mater. Chem. A, 2015, 3, 8926–8942.

- Zhou, Y., Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells, 2015, 143, 319–326.

- Messina, S., Thin Solid Films, 2016, 605, 204–210.

- Nair, M. T. S., Semicond. Sci. Technol., 2014, 29, 055006.

- Xiao, Z., Adv. Energy Mater., 2017, 7, 1602269.

- Chen, C., Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells, 2014, 122, 19–25.

- Wang, L., J. Mater. Chem. A, 2016, 4, 12386–12393.

- Birkett, M., J. Mater. Chem. A, 2018, 6, 1362–1370.

- Kwon, S. J., Sol. Energy, 2019, 188, 106–113.

- Sun, Y., J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 2015, 6, 4173–4179.

- Kim, J. Y., Appl. Phys. Lett., 2016, 109, 173903.

- Kumar, M., Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells, 2017, 160, 404–412.

- Tiwari, K. J., Thin Solid Films, 2018, 651, 78–84.

- Duan, H. S., Adv. Funct. Mater., 2013, 23, 1466–1471.

- Johnston, S., Acc. Chem. Res., 2016, 49, 146–154.

- Rockett, A., J. Appl. Phys., 2010, 108, 033702.

- Green, M. A., Third Generation Photovoltaics, Springer, 2006.

- Nelson, J., Physics of Solar Cells, Imperial College Press, 2003.

- Würfel, P., Physics of Solar Cells, Wiley, 2009.

- Rau, U., Appl. Phys. A, 2007, 86, 131–138.

- Polman, A., Nat. Mater., 2012, 11, 174–177.

- Nozik, A. J., Nano Lett., 2010, 10, 2735–2741.

- Tang, J., Nano Energy, 2016, 30, 207–214.

- Kim, H. S., J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 2014, 5, 2927–2934.

- Saliba, M., Energy Environ. Sci., 2016, 9, 1989–1997.

- Park, N. G., Mater. Today, 2015, 18, 65–72.

- Green, M. A., Prog. Photovolt., 2022, 30, 3–12.

- Grätzel, M., Acc. Chem. Res., 2017, 50, 487–491.

- Kim, G. Y., Energy Environ. Sci., 2020, 13, 2994–3003.

- Yoo, J. J., Nature, 2021, 590, 587–593.

- Jeong, M., Science, 2021, 372, 161–166.

- Green, M. A., Nat. Energy, 2016, 1, 15015.

- Polman, A., Science, 2016, 352, aad4424.

- Shockley, W.; Queisser, H. J., J. Appl. Phys., 1961, 32, 510–519.

- Würfel, P., Physics of Solar Cells, Wiley-VCH, 2009.

- Rau, U., Phys. Rev. B, 2007, 76, 085303.

- Tang, J., Chem. Rev., 2010, 110, 421–442.

- Hodes, G., Chem. Rev., 2008, 108, 4060–4077.

- Walsh, A., J. Phys. Chem. C, 2015, 119, 5755–5760.

- Yin, W. J., J. Mater. Chem. A, 2015, 3, 8926–8942.

- Zhou, Y., Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells, 2015, 143, 319–326.

- Messina, S., Thin Solid Films, 2016, 605, 204–210.

- Nair, M. T. S., Semicond. Sci. Technol., 2014, 29, 055006.

- Xiao, Z., Adv. Energy Mater., 2017, 7, 1602269.

- Chen, C., Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells, 2014, 122, 19–25.

- Wang, L., J. Mater. Chem. A, 2016, 4, 12386–12393.

- Birkett, M., J. Mater. Chem. A, 2018, 6, 1362–1370.

- Kwon, S. J., Sol. Energy, 2019, 188, 106–113.

- Sun, Y., J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 2015, 6, 4173–4179.

- Kim, J. Y., Appl. Phys. Lett., 2016, 109, 173903.

- Kumar, M., Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells, 2017, 160, 404–412.

Result and Discussion: The Fig. 2 (a) plots transmittance (%) on the y-axis (0–40%) against wavelength (nm) on the x-axis (500–1000 nm), with a blue curve labeled “Sb₂Se₃”. The film shows moderate transparency starting at ~35–40% around 900–1000 nm in the near-infrared (NIR) region, where longer wavelengths pass through with minimal absorption. As wavelength decreases toward the visible range (500–800 nm), transmittance drops sharply from ~30% at 850 nm to near 0% below 700 nm, indicating a distinct absorption edge. This behaviour reflects the fundamental absorption process where photons with energy exceeding the bandgap (~1.5 eV, corresponding to ~825 nm) are strongly absorbed, while lower-energy NIR photons transmit—ideal for top-cell applications in tandem solar cells or single-junction devices targeting AM1.5G spectrum utilization.Directly adjacent Fig. 2 (b) absorbance (arbitrary units, 0–1.4) versus wavelength (500–1000 nm) is shown in red (“Sb₂Se₃”),

You must be logged in to post a comment.