Sachin Nandre1,* Bhushan Nikam2, Hemangi Patil 3

1,Department of Physics, NSS’S Uttamrao Patil arts and sci.college, Dahiwel Dhule, India.,

2 Department of Physics, Kai.Sau.G.F.Patil Jr. College, Shahada Nandurbar, India,

3,Department of Chemistry, Kai.Sau.G.F.Patil Jr. College, Shahada Nandurbar, India,

* Author for correspondance (bhushannikam81@gmail.com)

ABSTRACT –

This study presents a systematic correlation between morphology, elemental composition, and optical behaviour of Group IB and IIB transition-metal tartrate crystals investigated using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray analysis (EDAX), and ultraviolet (UV) spectroscopy. The combined results establish a strong interdependence between structural characteristics, chemical composition, and optical response, underscoring the significant role of transition metal ions in tailoring the physicochemical properties of tartrate crystals. These findings highlight the potential of such materials for applications in optical and other functional material systems.

Keywords: SEM, EDAX and UV spectroscopic; Optical Behaviour; Transition metal

INTRODUCTION –

Tartrate crystals have attracted significant research interest due to their ferroelectric and piezoelectric properties, as well as their applicability in transducers and both linear and nonlinear mechanical devices. [1-3]. The gel growth technique is one of the simplest and most effective methods for growing sparingly soluble crystals from aqueous solutions, enabling crystal formation under ambient conditions at relatively low temperatures. [4]. Nonlinear optical (NLO) materials play a vital role in optoelectronic applications such as optical frequency conversion, optical data storage, and optical switching in inertial confinement laser fusion systems. To effectively realize these applications, materials exhibiting strong second-order optical nonlinearities, a short transparency cut-off wavelength, and high thermal and mechanical stability are required. [5] In metal–organic coordination complexes, the nonlinear optical (NLO) response is predominantly governed by the organic ligand. With respect to the metallic component, particular attention is given to Group IIB metals (Zn, Cd, Hg, and related ions), as their compounds exhibit high transparency in the ultraviolet region. It is well established that crystal morphology is determined by the interplay between the driving force for crystallization and the diffusion of atoms, ions, molecules, or heat. Variations in these experimental parameters can significantly alter crystal growth behavior, leading to morphological transitions from well-defined polyhedral forms to skeletal and dendrite structures. [6] The growth of single crystals of Calcium tartrate was reported [7] and single crystals of strontium tartrate was reported [8].Thermal studies on tartrate crystals grown by gel method were reported by many investigators [9-11]. Tartrate crystals are of considerable interest, particularly for basic studies of some of their interesting physical properties. Some crystals of this family are ferroelectric [12-14], some others are piezoelectric [15] and quite a few of them have been used for controlling laser emission [16]. The present work investigates the structural, nonlinear, and optical properties of Group IB and IIB transition-metal tartrate crystals, Furthermore, a comprehensive correlation between crystal morphology, elemental composition, and optical behavior was established through combined SEM–EDAX and UV spectroscopic investigations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS –

Raw material for the growth of the tartrate compound was synthesized by mixing aqueous solutions of Tartaric acid (C4H6O6 ) Sodium meta Silicate – Na2SiO3 and IB and IIB transition metal such as Copper chloride (CuCl2.2H20,), Mercuric chloride (HgCl2) and Cadmium chloride monohydrate (CdCl2.H2O 99 %) with Double distilled water in the amount of specific ratio. The solution was allowed to flow along the test tube wall to prevent cracking of the gel surface. Subsequently, Cu²⁺, Hg²⁺ and Cd²⁺ ions slowly diffused into the gel medium, where they reacted with the inner reactant, resulting in crystal growth.[17] And the corresponding chemical reaction is –

- C4H606 + CuCl2→ C4H406Cu + 2HCl

- HgCl2 + C4H6O6 → HgC4H4O6 + 2HCl

- C4H6O6 + CdCl2 → C4H4O6Cd + 2HCl

RESULT AND DISCUSSION

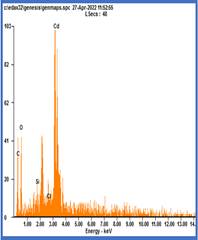

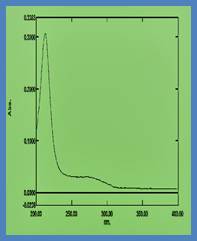

Fig- SEM , EDAX and UV –Vis

From the optimum growth conditions of copper, mercury, and cadmium tartrate crystals, it is observed that the gel setting time, gel aging time, and crystal growth period vary with different dopants. SEM–EDAX and UV–Vis studies reveal a clear correlation among crystal morphology, elemental composition, and optical behavior.

CHARECTORIZATION STUDY

The crystallographic parameters of the grown crystals were determined from the measured interaxial angles and were found to correspond to orthorhombic and monoclinic crystal systems. UV–Vis spectral analysis revealed that the optical band gap values of all selected Group IB and IIB tartrate crystals are nearly identical, with values of 5.69 eV, 5.87 eV, and 5.85 eV for copper, mercury, and cadmium tartrate crystals, respectively. SEM microstructural analysis indicated distinct surface morphologies for each crystal: copper tartrate exhibited coral reef–like rock structures, mercury tartrate showed coral blossom or octocoral polyp–like features resembling tiny sea flowers, while cadmium tartrate displayed small stone pebble–like and plate–like structures with cut-flower appearances. EDAX analysis confirmed the elemental composition by showing characteristic peaks of copper, mercury, and cadmium, along with silicon, oxygen, carbon, sodium, and chlorine, thereby validating the formation of copper, mercury, and cadmium tartrate crystals.

CONCLUSION

The present study establishes a clear correlation between crystal morphology and the nature of the incorporated transition metal ions in Group IB and IIB tartrate crystals. SEM studies reveal that the crystal morphology of Group IB and IIB metal tartrates is strongly dependent on the type of incorporated metal ion and growth conditions. The observed variations in surface features are well supported by EDAX-confirmed composition and are consistent with the optical behaviour obtained from UV analysis. This correlation highlights the decisive role of metal–ligand interactions in governing the morphological and physicochemical properties of tartrate crystals. Overall, the combined SEM–EDAX–UV analysis demonstrates that crystal morphology is closely linked to elemental composition and plays an important role in governing the optical behavior of transition metal tartrate crystals.

REFRENCES:

[1] R. Mazake ,T. Buslaps ,R.Claessen.J.Fink. Mater. Europhys. Lett.Volume9 (5), pp. 477, 1989

[2] F. Jesu , D. Arivuoli ,S.Ramasamy. Material Resarch Bulletin. Volume 29, Page 309, 1994

[3] M. E. Torres , T. Lopez ,J.Peraza . Journal of Applied Physics. Volume 84, Page 5729, 1998

[4] N. H. Manani , Jethva Int.Journal of Scentific research in physics Lett. Vol. 8, Page 08, 2020

[5] S.Kalaiselvan , G. Pasupathi,B.Sakthivel . Der Pharma Chemica. Volume 4(5), Page 1826, 2012

[6] D. K. Sawant , H.M.Patil ,D.S.Bhavsar,J.H.Patil ,K.D.Girase. Archives of physics Resarch,Volume 2(2) ,Page 67-73, 2011

[7] S. M. Dharma Prakash , P. Mohan Rao J.. Mater. Sci Lett. Volume 5, Page 769, 1986

[8] M.H. Rahimkutty, Rajendra Babu ,K. Shreedharan Bull. mater. Sci., Volume 24,Page 249-, 2001.

[9] H.K. Henisch., Crystal growth in gels, University park,PA ; The Pennsylvania university 1973.

[10] P.N. Kotru, N.K. Gupta, K. K. Raina,M.L. Koul, Bull.Mater. Sci. Volume 8 Page 5471986

[11] P.N. Kotru, N.K. Gupta, K. K. RainaL.B.Sarma, Bull. Mater. Sci. Volume 21,Page 83,1986

[12]M. M. Abdel-Kader, FI-Kabbany, S. Taha, M. Abosehly, K. K. Tahoon, and A. EISharkay,

J. Phys. Chem. Sol, Volume 52,Page 655, 1991.

[13] H. B. Gon, J. Cryst. Growth, Volume 102,Page 501,1990

[14] C. C. Desai and A. H. Patel, J. Mat. Sci. Lett, Volume 6, Page 1066, 1987.

[15] V. S. Yadava and V. M. Padmanabhan, Acta. Cryst, B Volume 29,Page 493, 1973.

[16] L. V. Pipree and M. M. Kobklova, Radio Eng. Electron Phys, (USA),Volume 12,Page 33,1984.

[17] B. P. Nikam, S. J. Nandre,C.P.Nikam. JETIR ,Volume 9 (2) , 2022.1984.