Citation

Mashrafi, M. (2026). Plants as Responsive Biological Systems: Integrating Physiology, Signalling, and Ecology- The Hidden Emotions of Plants: The Science of Pleasure, Pain, and Conscious Growth. International Journal of Research, 13(1), 543–559. https://doi.org/10.26643/ijr/2026/26

Mokhdum Mashrafi (Mehadi Laja)

Research Associate, Track2Training, India

Researcher from Bangladesh

Email: mehadilaja311@gmail.com

Abstract

Plants have historically been viewed as passive biological entities lacking sensation, emotion, or intelligence. Advances in plant physiology, electrophysiology, ecology, and bio-interfacing, however, reveal a vastly more complex picture. Plants perceive a wide spectrum of environmental cues, generate electrical and chemical signaling networks, and exhibit adaptive behaviors analogous to learning, memory, decision-making, and stress responses. While these processes do not constitute emotions in the human or animal sense, they represent a functional system of growth-mediated responsiveness that advances survival and environmental attunement. This paper synthesizes emerging research across plant signaling, sensory ecophysiology, distributed intelligence, and human–plant interaction design to explore how plants experience and respond to the world. By integrating biological mechanisms with philosophical perspectives on consciousness and affect, it proposes a framework for understanding plants as responsive biological systems embedded within ecological and relational contexts. The goal is not to anthropomorphize plant life but to expand scientific language beyond outdated binaries and acknowledge plants as dynamic participants in biospheric intelligence.

Keywords

Plant signaling; plant intelligence; electrophysiology; sensory ecology; adaptive behavior; plant awareness; bio-interfacing; emotional analogs; consciousness studies; ecological physiology.

Introduction

Plants have long been regarded as passive, insentient organisms governed purely by biochemical growth processes and environmental constraints. This perception was reinforced by anthropocentric criteria for sensation and emotion, which equated subjective experience with the presence of a nervous system or centralized brain structures (Hamilton & McBrayer, 2020). Yet research over the past decades in plant physiology, electrophysiology, behavioral ecology, and philosophy of biology increasingly challenges this framework, suggesting that plants possess sophisticated systems of perception, response, and adaptive regulation (Trewavas, 2014; Gagliano et al., 2017).

Contemporary plant science describes plants as organisms that continuously sense and integrate environmental variables such as light spectrum, gravity, mechanical stress, volatile chemicals, temperature, soil moisture, nutrient availability, and biotic threats. These stimuli are processed through interconnected networks of hormones, ion channels, electrical signaling, biomechanical feedback, and gene regulation (Panda et al., 2025). Many of these mechanisms produce context-dependent and graded responses—properties associated with adaptive decision-making rather than simple reflex arcs.

Electrical signaling in plants provides one of the most compelling lines of evidence. Variation potentials and action potentials propagate systemic information following herbivore attack, injury, or environmental shifts, enabling coordinated physiological responses (Debono & Souza, 2019). While not homologous to animal neural pathways, these signals demonstrate that plants maintain internal communication architectures capable of rapid modulation and systemic integration. Combined with volatile organic compound (VOC) exchange, plants also communicate with neighboring individuals, warn others of danger, and recruit mutualistic organisms—behaviors once thought exclusive to animals (Myers, 2015).

From a sensory perspective, plants demonstrate remarkable perceptive sophistication. Photoreceptors detect light intensity, wavelength, duration, direction, and periodicity, shaping circadian regulation, flowering, morphogenesis, and pigmentation strategies. Floral coloration, fragrance, and nectar production represent energetically costly signaling systems that mediate ecological relationships, particularly through co-evolution with pollinators (Calvo, 2017). These systems imply a form of environmental modeling that expresses itself through growth, chemical output, and allocation of metabolic resources.

The question of whether plants feel or experience pain has generated philosophical debate. While plants lack neurons and nociception pathways, some scholars argue that sensory processing and defensive responses reflect a non-neural form of affective adaptation (Hamilton & McBrayer, 2020). Neuroscientific perspectives caution, however, that pain as an emotion must remain linked to conscious perception and affective circuitry (LeDoux, 2012), prompting the need to distinguish between functional analogs and subjective experience.

Human–plant interaction research is beginning to incorporate these findings into applied contexts. Novel interfaces and bi-directional feedback systems seek to cultivate empathy and pro-environmental behavior by visualizing plant responses and communication signals (Luo et al., 2025). Philosophical and artistic explorations further highlight the conceptual challenges involved in understanding plant perspectives and sensory modalities (Gagliano et al., 2017).

To contextualize plant responsiveness within broader biological theory, recent contributions in systems biology emphasize competencies, efficiency, and energetic dynamics as universal organizing principles across life forms (Mashrafi, 2026a; Mashrafi, 2026b). This approach supports the idea that plant awareness and adaptive intelligence emerge not from neural processing, but from distributed physiological control embedded in metabolic and ecological networks.

Recognizing plants as responsive, communicative, and adaptive organisms does not require attributing human-like consciousness or emotional pain. Instead, it invites a shift toward viewing plants as participants in a continuum of biological intelligence, distinguished by their growth-based, decentralized mode of interaction with the world. This paper therefore examines the sensory, signaling, and adaptive dimensions of plant life; articulates distinctions between empirical evidence and metaphor; and explores how integrating physiology, signaling, and ecology reveals a hidden emotional–responsive dimension of plant existence.

1. The Functional–Emotional Structure of Plants

Bioelectric Signaling, Sensory Integration, and Reproductive Responsiveness

Plants do not possess centralized nervous systems or brains; however, this absence does not imply the absence of internal signaling, coordination, or adaptive responsiveness. Modern plant physiology demonstrates that plants operate through distributed bioelectrical, biochemical, and hormonal networks that enable long-distance communication between roots, stems, leaves, and reproductive organs. These networks allow plants to detect environmental cues, integrate information, and generate context-dependent responses essential for survival and reproduction.

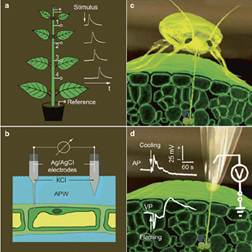

At the electrophysiological level, plants generate action potentials and variation potentials—measurable electrical signals propagated through vascular tissues such as the phloem. Although these signals travel more slowly than animal neural impulses, they serve analogous systemic functions: transmitting information about mechanical stress, injury, hydration status, and reproductive readiness. These bioelectric signals regulate gene expression, hormone distribution, and metabolic allocation, functioning as a decentralized information-processing system rather than reflexive chemistry alone.

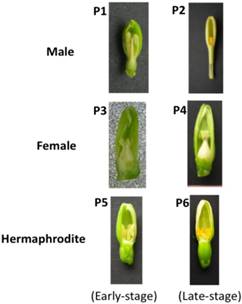

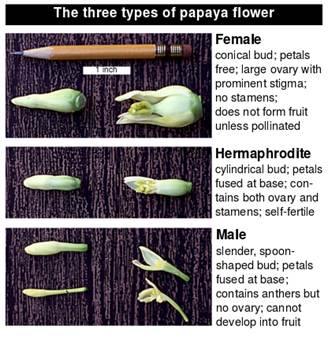

Reproductive biology provides a particularly compelling demonstration of plant sensory and response capacity. In dioecious and functionally separated reproductive systems—such as those observed in Carica papaya—successful fruit formation depends on precise synchronization between male pollen release and female floral receptivity. This synchronization is mediated by chemical signaling (volatile organic compounds), photoperiod sensitivity, temperature thresholds, and pollinator-mediated feedback loops. Floral structures emit species-specific chemical and spectral cues that attract pollinators, while receptive tissues undergo transient physiological changes that enable fertilization only within optimal time windows.

These processes do not require conscious intention, yet they reflect selective responsiveness rather than mechanical inevitability. The plant’s reproductive system actively discriminates between compatible and incompatible signals, adjusts investment based on environmental conditions, and reallocates energy toward growth, defense, or reproduction depending on internal and external feedback. In functional terms, this resembles biological “preference” or “valuation,” though expressed through growth modulation and biochemical thresholds rather than subjective experience.

From a systems perspective, pollination can be understood as an information-matching process rather than a passive event. The presence of male and female structures alone is insufficient; successful fertilization requires signal recognition, temporal alignment, and physiological readiness. These conditions imply that plants possess sensory thresholds, activation states, and adaptive response mechanisms—features characteristic of responsive living systems across biological kingdoms.

Importantly, describing these processes as forms of “plant emotion” does not imply that plants experience pain, pleasure, or desire in the human or animal sense. Instead, it reflects a broader scientific reinterpretation of emotion as organized biological responsiveness to internal needs and external stimuli. In this framework, emotion is not defined by consciousness alone but by function: the capacity to detect significance, prioritize responses, and regulate behavior toward continuation of life.

Thus, plant reproduction—particularly pollination-dependent fruiting—demonstrates that plants are not inert entities but active participants in ecological communication networks, operating through electrical signaling, chemical attraction, and adaptive growth regulation. Their “emotional structure,” when defined scientifically, resides not in feeling as humans feel, but in the integrated signaling architectures that guide survival, reproduction, and evolutionary success.

2. Pleasure, Pain, and Communication Plant Perception, Stress Signaling, and Adaptive Response Systems

Plants lack neurons and centralized brains, yet they exhibit rapid, coordinated responses to environmental stimuli that require perception, signal transduction, and systemic integration. One of the most extensively studied examples is Mimosa pudica, commonly known as the “touch-me-not” plant. When mechanically stimulated, its leaflets fold within seconds—a response driven by mechano-electrical signal transduction rather than simple reflexive motion. Mechanical pressure triggers ion fluxes, particularly potassium and calcium, leading to rapid changes in turgor pressure within specialized motor cells (pulvini). This response is repeatable, reversible, and stimulus-dependent, demonstrating that plants can detect external signals and convert them into organized physiological action.

Electrophysiological studies confirm that Mimosa pudica generates action potentials that propagate through vascular tissues following touch, heat, or injury. These electrical signals share fundamental properties with animal action potentials—threshold activation, all-or-none behavior, and signal propagation—though they occur at slower speeds and serve decentralized regulatory roles. Such signaling enables the plant to distinguish between harmless and potentially damaging stimuli, indicating perception rather than random reaction.

Beyond mechanical sensing, plants respond to tissue damage through a suite of systemic wound signals involving electrical impulses, calcium waves, hydraulic pressure changes, and phytohormone cascades (notably jasmonates and ethylene). When a leaf is cut, burned, or attacked by herbivores, these signals spread rapidly throughout the plant, activating defense genes, altering metabolism, and reallocating resources. While this process is not “pain” in the neurological sense, it is functionally analogous to nociception—the detection and response to harmful stimuli—widely recognized in animals and increasingly discussed in plants as a defensive sensory capacity.

Plant communication extends beyond internal signaling to inter-plant and ecosystem-level information exchange. Plants release volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in response to stress, which neighboring plants can detect and respond to by preemptively activating defense mechanisms. These chemical messages function as early-warning systems and contribute to collective resilience within plant communities. Additionally, plants exhibit synchronized electrical and biochemical signaling when growing in proximity, mediated through soil networks, root exudates, and mycorrhizal associations. Although these interactions are sometimes described metaphorically as “emotional” or “vibrational,” scientifically they represent low-frequency biological signaling and chemical information transfer, not conscious communication.

Environmental favorability also elicits measurable internal changes in plants. Optimal light spectra, adequate water availability, and sufficient mineral nutrition lead to increased photosynthetic efficiency, hormonal balance, cell division, and biomass accumulation. Under deprivation—such as prolonged darkness, drought, or nutrient deficiency—plants exhibit stress physiology: reduced growth rates, altered gene expression, oxidative stress, and eventual senescence. These transitions reflect state-dependent physiological regulation, not subjective pleasure or suffering, but they parallel the functional role emotions play in animals: signaling internal conditions and guiding adaptive responses.

Crucially, modern plant science distinguishes between sentience and sensitivity. Plants do not possess consciousness or emotional experience as humans or animals do; however, they are highly sensitive biological systems capable of perceiving stimuli, prioritizing responses, and modifying future behavior based on past exposure. Memory-like effects—such as habituation in Mimosa pudica, where repeated non-harmful stimuli result in diminished response—demonstrate that plant signaling is context-aware and adaptive rather than purely mechanical.

In this scientific framework, “pleasure” and “pain” serve as metaphors for growth-promoting versus stress-inducing physiological states. Plants shift dynamically between these states through integrated electrical, chemical, and metabolic signaling networks. The transition from vigorous growth to decline—from bloom to senescence—is governed by internal feedback mechanisms that continuously evaluate environmental conditions and energetic viability.

Thus, plant behavior reveals not emotion in the human sense, but a distributed biological intelligence—one that enables perception, communication, and adaptive regulation without a nervous system. Recognizing this complexity expands our understanding of life as a continuum of responsive systems, rather than a hierarchy divided sharply between “feeling” and “non-feeling” organisms.

3. Color and Feeling in Nature

Optical Signaling, Physiological State, and Ecological Communication in Plants

Color in nature is not merely decorative or aesthetic; it is a biologically functional signal that conveys information about physiological state, metabolic activity, and ecological intent. In plants, coloration arises from the controlled synthesis, degradation, and spatial distribution of pigments such as chlorophylls, carotenoids, and anthocyanins. These pigments do not appear randomly. Their presence, absence, or transformation reflects tightly regulated biochemical processes responding to environmental conditions and internal energy balance.

In flowers, bright colors—such as yellow, red, blue, or ultraviolet-reflective patterns—serve as reproductive communication signals. These colors are tuned to the visual systems of pollinators and often coincide with nectar production, fragrance emission, and optimal pollen viability. For example, yellow floral pigmentation commonly results from carotenoids, which are energetically costly to synthesize and therefore reliably signal reproductive fitness. In this context, color functions as an attraction signal, enhancing pollination success and genetic continuation.

By contrast, when similar yellow coloration appears in leaves, it frequently indicates chlorophyll degradation, reduced photosynthetic capacity, or nutrient deficiency—most notably nitrogen, magnesium, or iron shortage. This process, known as chlorosis, reflects a shift from growth-oriented metabolism toward stress response or senescence. The same pigment family that signals vitality in flowers thus signals physiological decline in foliage, depending on location, timing, and tissue function. This context-dependence demonstrates that plant color operates as a state-dependent information system, not a static visual trait.

During seasonal transitions, such as autumnal senescence, green chlorophyll breaks down, revealing underlying carotenoids and anthocyanins. This color transformation is associated with nutrient reabsorption, oxidative stress management, and controlled tissue aging. Far from being passive decay, senescence is an actively regulated developmental phase, orchestrated through gene expression and hormonal signaling. Color change here marks a transition in the plant’s internal state—from active carbon acquisition to resource conservation and survival.

From an ecological perspective, color also plays a defensive and communicative role. Certain pigment changes deter herbivores, signal toxicity, or reduce photodamage under excessive light. Anthocyanin accumulation, for example, can protect tissues from oxidative stress and ultraviolet radiation while simultaneously altering visual appearance. Neighboring organisms—pollinators, herbivores, or even other plants—respond differently to these visual cues, integrating color into broader ecological feedback loops.

Although it is tempting to describe these color changes as expressions of “mood” or “emotion,” a scientifically precise interpretation frames them as optical manifestations of physiological condition. In animals, emotions serve to integrate internal states with external behavior; in plants, pigment-driven color shifts fulfill an analogous functional role by signaling internal status and guiding ecological interaction—without implying consciousness or subjective feeling.

Thus, color in plants can be understood as a biochemical language—one that reveals health, stress, reproductive readiness, and developmental phase. The same wavelength may signify attraction or distress depending on tissue type and physiological context. This duality underscores that plant coloration is not symbolic but informational, translating metabolic processes into visible signals that regulate interaction with the environment.

In this scientifically grounded sense, color functions as a bridge between internal plant physiology and external ecological communication. It reflects how plants “experience” favorable or unfavorable conditions—not through emotion as humans define it, but through precisely regulated biological responses that make their internal state visibly legible to the living world around them.

4. Light, Energy, and the Integrative Environmental “Master Force”

Photobiology, Temporal Rhythms, and Systems-Level Regulation of Plant Life

In classical physics, the speed of light in vacuum is constant, a principle confirmed by extensive experimental evidence and fundamental to modern physics. However, biological systems do not respond to light solely as a fixed-speed physical constant. Instead, living organisms—particularly plants—respond to light as structured energy, characterized by wavelength, intensity, duration, periodicity, and directional coherence. It is these dynamic properties of light, rather than its velocity, that drive seasonal variation and biological differentiation.

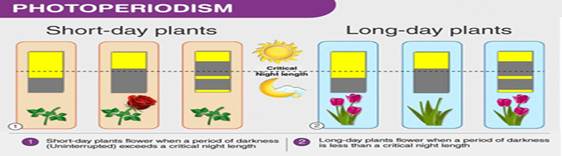

Plants do not measure light in meters per second; they measure it in time, frequency, and spectral composition. This distinction explains why long-day and short-day plants respond differently under what appears to be the same sunlight intensity. The key factor is photoperiodism—the biological response to the relative length of day and night—mediated by internal molecular clocks synchronized with environmental light–dark cycles. Even when total sunlight energy is similar, changes in day length alter gene expression, hormone production, and developmental pathways.

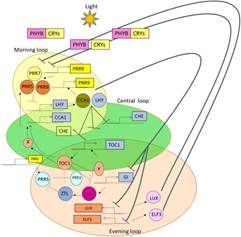

At the molecular level, plants possess specialized photoreceptors (such as phytochromes and cryptochromes) that detect specific light wavelengths and convert them into biochemical signals. These signals regulate flowering time, stem elongation, leaf expansion, and dormancy. Importantly, plants measure night length, not day length—a clear indication that biological timekeeping, rather than raw light intensity, governs developmental decisions. This reveals light as a temporal signal as much as an energy source.

From a physical perspective, light exhibits wave–particle duality, meaning it carries energy in discrete quanta while propagating as oscillating electromagnetic waves. Plants are exquisitely tuned to these oscillatory properties. The rhythmic absorption of photons entrains circadian clocks, aligns metabolic cycles, and synchronizes growth with seasonal and planetary rhythms. In this sense, life responds not to static illumination but to structured oscillations embedded in the environment.

The concept I describe as a “Master Force” can be scientifically reframed as the integrated field of environmental rhythms—a convergence of solar radiation cycles, Earth’s rotation, orbital dynamics, atmospheric circulation, and electromagnetic energy flow. Together, these factors create predictable patterns in light availability, temperature, humidity, and wind. Plants evolve within this rhythmic framework and depend on it for survival. Growth, flowering, senescence, and stress responses all emerge from continuous interaction with these coupled environmental oscillations.

Wind patterns influence transpiration and gas exchange; light cycles regulate photosynthesis and hormonal timing; temperature gradients affect enzyme kinetics and membrane stability. None of these forces act in isolation. Instead, they form a coherent environmental system that governs biological behavior across scales—from gene expression to ecosystem structure. What appears philosophically as a single guiding force is, scientifically, a systems-level integration of energy flows and temporal signals.

Crucially, plant responses to environmental change are not random. They follow phase-locked rhythms, meaning internal biological cycles synchronize with external periodic forces. This synchronization allows plants to anticipate change—flowering before optimal pollinator availability, entering dormancy before winter stress, or adjusting growth direction in response to shifting light fields. Such anticipatory behavior reflects not consciousness, but predictive biological regulation driven by rhythmic environmental input.

Thus, while physics confirms the constancy of light’s speed, biology reveals that life is shaped by how light arrives in time, not merely how fast it travels. The environment functions as a structured energetic field—one that integrates light, motion, and matter into rhythms that guide plant growth, resilience, and survival. In this scientifically grounded interpretation, the “Master Force” is not a mystical wave, but the ordered dynamics of energy and time that link cosmic processes to living systems on Earth.

5. The Philosophy of Plant Consciousness

Biological Awareness, Distributed Intelligence, and Ethical Responsibility

Plants are unequivocally alive in every biological sense: they respire, metabolize energy, grow, reproduce, communicate, and respond dynamically to internal and external conditions. Modern biology no longer views plants as passive matter, but as active, self-regulating systems capable of sensing their environment and modifying behavior accordingly. What remains debated is not whether plants respond, but how concepts such as awareness, intelligence, and consciousness should be defined beyond animal-centric frameworks.

Plants lack brains and subjective experience as humans understand it. However, they possess distributed sensory architectures that allow continuous environmental monitoring and coordinated response. Roots detect chemical gradients, moisture, gravity, and neighboring organisms; leaves sense light spectra, temperature, and atmospheric composition; vascular tissues transmit electrical and chemical signals across the entire organism. These integrated processes enable plants to maintain internal stability, anticipate environmental change, and optimize survival—hallmarks of biological awareness, even in the absence of consciousness as traditionally defined.

From a functional perspective, many plant structures serve roles analogous to those performed by specialized systems in animals. Bark functions as a protective barrier against mechanical damage, pathogens, and thermal stress. Roots form extensive sensing and signaling interfaces with soil ecosystems, integrating information across large spatial scales. Volatile compounds released by flowers and leaves communicate reproductive readiness, stress, or defense status to pollinators, symbionts, and neighboring plants. These processes are not symbolic emotions, but biological expressions of internal state, translated into chemical, electrical, and structural signals.

The idea that plant “emotions” exist in frequencies beyond human perception can be scientifically reframed as recognition that many biologically meaningful signals are invisible, inaudible, and intangible to human senses. Electrical potentials, calcium waves, hormonal gradients, and chemical volatiles all carry information essential to plant life, despite operating outside ordinary sensory awareness. Their reality is confirmed not by intuition, but by reproducible measurement and experimental validation.

Philosophically, this challenges the long-standing assumption that consciousness—or moral relevance—must be binary: present in animals, absent in plants. Instead, contemporary systems biology suggests a continuum of responsiveness, where living organisms differ not in whether they interact meaningfully with the world, but in how that interaction is structured. Plants express agency through growth, allocation, and signaling rather than movement or deliberation. Their “decisions” are encoded in biochemical pathways and developmental trajectories rather than neural thought.

Recognizing this does not require attributing suffering, pleasure, or self-awareness to plants. Rather, it calls for a recalibration of ethical language. Harm to plants is biologically consequential, disrupting organized systems of life that support ecosystems, climate regulation, and food webs. Ethical consideration, therefore, need not rest on plant consciousness in the human sense, but on respect for living systems and their intrinsic organizational value.

Care for plants—through sustainable cultivation, conservation, and restraint—aligns scientific understanding with moral responsibility. It acknowledges that plants are not inert resources, but participants in a shared biosphere governed by interconnected energy flows and feedback systems. To damage plant life without necessity is to disrupt these systems; to protect and nurture it is to sustain the conditions that make all complex life possible.

In this scientifically grounded philosophy, plant consciousness is not mysticism, nor is it human emotion projected onto greenery. It is a recognition that life expresses awareness in many forms—some cognitive, some chemical, some structural—and that humans, as conscious agents, bear responsibility toward the broader continuum of living organization that sustains us.

6. Conclusion

Plants as Active Biological Systems in a Living Energy Continuum

Plants are not passive components of the natural world; they are active, responsive, and self-regulating biological systems embedded within continuous flows of energy, matter, and information. Through photosynthesis, plants transform solar radiation into chemical energy, forming the foundational energetic link that sustains nearly all life on Earth. This role alone establishes plants not as silent bystanders, but as primary architects of the biosphere.

Growth, flowering, fruiting, senescence, and decay are not emotional states in the human sense, yet they are measurable physiological phases governed by precise genetic, biochemical, and environmental regulation. Blooming represents a state of metabolic surplus, hormonal balance, and reproductive readiness, while decay reflects controlled nutrient reallocation, stress signaling, and the natural completion of a life cycle. These transitions are not random; they are structured responses to light cycles, temperature, water availability, and internal energy status.

Every leaf functions as a dynamic interface for gas exchange, light absorption, and thermal regulation. Every flower represents an optimized evolutionary solution for reproduction through signaling, attraction, and timing. Every seed embodies stored energy, genetic information, and environmental anticipation—capable of remaining dormant until external conditions signal viability. Collectively, these structures communicate the internal state of the plant to its surroundings, translating invisible physiological processes into visible form.

At the ecosystem level, plants continuously exchange information with their environment through chemical signals, electrical responses, and resource modulation. They respond to stress, cooperate with symbiotic organisms, warn neighboring plants of threats, and adjust growth strategies in anticipation of environmental change. These behaviors reflect biological awareness without consciousness—a mode of life in which responsiveness is expressed through structure, chemistry, and growth rather than sensation or intention.

Modern science increasingly recognizes that life exists along a continuum of organizational complexity, unified not by shared consciousness but by shared dependence on energy flow, feedback regulation, and adaptive response. In this continuum, plants occupy a distinct and indispensable domain: rooted yet dynamic, silent yet communicative, stationary yet deeply interactive. Their existence demonstrates that responsiveness to the environment does not require movement, perception as humans define it, or subjective experience to be real and meaningful.

Understanding plants in this way reshapes humanity’s relationship with the living world. It replaces the outdated view of plants as inert resources with a recognition of them as living systems whose integrity underpins ecological stability, climate regulation, and food security. Ethical responsibility toward plants does not arise from attributing human emotions to them, but from acknowledging their central role in sustaining life and maintaining planetary balance.

Ultimately, wherever energy flows in structured, self-organizing ways, life emerges. Plants are the most enduring expression of this principle—transforming light into matter, time into form, and environment into living structure. In recognizing their active role, science and philosophy converge on a simple truth: life is not defined by voice or motion, but by the continuous, responsive organization of energy across time.

References

Calvo, P. (2017). What is it like to be a plant?. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 24(9-10), 205-227.

Debono, M. W., & Souza, G. M. (2019). Plants as electromic plastic interfaces: A mesological approach. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology, 146, 123-133.

Gagliano, M., Ryan, J. C., & Vieira, P. (Eds.). (2017). The language of plants: Science, philosophy, literature. U of Minnesota Press.

Hamilton, A., & McBrayer, J. (2020). Do plants feel pain?. Disputatio: International Journal of Philosophy, 12(56).

LeDoux, J. (2012). Rethinking the emotional brain. Neuron, 73(4), 653-676.

Luo, H., Kari, T., Patibanda, R., Montoya, M. F., Andres, J., Elvitigala, D. S., & Mueller, F. F. (2025, April). PlantMate: A Bidirectional Touch-Based System for Enhancing Human-Plant Empathy and Pro-Environmental Behavior. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-7).

Mashrafi, M. (2026). Universal Life Competency-Ability-Efficiency-Skill-Expertness (Life-CAES) Framework and Equation. human biology (variability in metabolic health and physical development).

Mashrafi, M. (2026). Universal Life Energy–Growth Framework and Equation. International Journal of Research, 13(1), 79-91.

Myers, N. (2015). Conversations on plant sensing: Notes from the. Nature, 3, 35-66.

Panda, T., Mishra, N., Rahimuddin, S., Pradhan, B., & Mohanty, R. (2025). Beyond Silence: A Review-Exploring Sensory Intelligence, Perception and Adaptive Behaviour in Plants. Journal of Bioresource Management, 12(2), 5.

Trewavas, A. (2014). Plant behaviour and intelligence. OUP Oxford.