Rahul Patil1*, Sunil Sajgane1, Suraj Vasave1, Sandip Patil2

1 Y.C.S.P. Mandal’s Dadasaheb Digambar Shankar Patil Arts, Commerce and Science College, Erandol 425109, Maharashtra, India.

2 N.T.V.S’s G. T. Patil Arts, Commerce and Science College, Nandurbar 425412, Maharashtra, India.

Corresponding Author Email Id: rahul92ppatil@gmail.com

———————————————————————————————————————

Abstract:

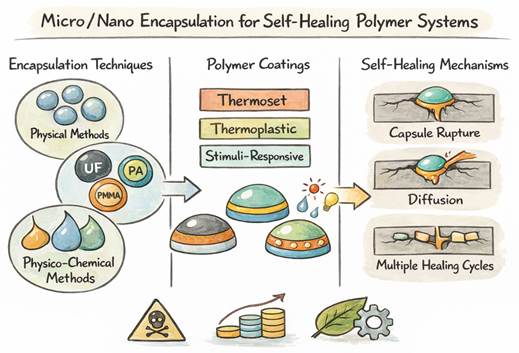

Self-healing materials have garnered significant interest for their ability to autonomously repair damage, improve reliability, and extend the service life of polymer systems. Among various strategies, micro- and nano-encapsulation of healing agents combined with polymeric coatings has emerged as an effective approach, enabling controlled release, protection of active agents, and enhanced mechanical performance. This review highlights recent advances in encapsulation techniques, including physical, chemical, and physico-chemical methods, and examines the influence of capsule size, shell thickness, and morphology on healing efficiency. The selection of polymer coatings thermoset, thermoplastic, and stimuli-responsive is discussed in relation to mechanical reinforcement, environmental resistance, and triggerable release mechanisms. Key self-healing mechanisms, such as capsule rupture, diffusion-based repair, and multi-cycle healing, are summarized. Current challenges, including material compatibility, environmental concerns, cost, and scalability, are addressed, along with future perspectives on sustainable materials, multi-functional coatings, and smart self-healing systems for applications in composites, coatings, electronics, and biomedical devices.

Graphical Abstract:

Keywords: Encapsulation, Self-Healing Coating, Thermoset, Thermoplastic

- Introduction:

The growing demand for durable, reliable, and sustainable materials has driven extensive research into self-healing polymer systems capable of autonomously repairing damage and restoring functionality [1,2]. Microcracks generated during service are often precursors to catastrophic failure in polymeric materials and composites, particularly in structural, coating, and electronic applications [3]. Conventional repair strategies are typically labor-intensive, costly, and impractical for inaccessible or microscale damage, motivating the development of materials with intrinsic or extrinsic self-healing capabilities. Among the various self-healing approaches, the encapsulation of healing agents within micro- or nano-sized containers represents one of the most widely investigated and practically viable strategies [2,4]. In encapsulation-based self-healing systems, liquid or solid healing agents are stored within discrete capsules embedded in a polymer matrix. Upon crack initiation and propagation, these capsules rupture or activate, releasing the healing agent into the damaged region where it undergoes polymerization, crosslinking, or physical consolidation, thereby sealing the crack and partially or fully restoring mechanical integrity [5,6].

Micro‑ and nano‑encapsulation offers several advantages over other self‑healing strategies, including effective protection of sensitive healing agents, controlled release behavior, and compatibility with a broad range of polymer matrices [5]. Capsule size plays a critical role in determining healing efficiency, dispersion uniformity, and mechanical performance of the host material. While microcapsules are effective for delivering sufficient quantities of healing agents, nanocapsules provide improved dispersion, reduced stress concentration, and the potential for multiple healing events [7]. Polymer coating or shell materials are a key component of encapsulation‑based self‑healing systems, as they govern capsule stability, mechanical strength, interfacial adhesion, and rupture behavior [2,8]. Commonly employed polymer shells include urea–formaldehyde, melamine–formaldehyde, polyurethane, polyurea, and hybrid shells decorated with inorganic nanolayers for enhanced stability [9]. Recent research has increasingly focused on tailoring polymer coatings through chemical modification or the use of stimuli-responsive polymers to enhance healing efficiency and durability under complex service conditions [8,9]. Despite significant progress, several challenges remain in the large-scale implementation of polymer-coated micro/nano-encapsulation systems, including synthesis scalability, capsule–matrix compatibility, long-term stability, and environmental concerns associated with certain shell materials [2,10]. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of encapsulation synthesis methods, polymer coating strategies, and their influence on self-healing performance is essential.

This review aims to summarize and critically discuss recent advances in micro- and nano-encapsulation techniques and polymer coating materials used for self-healing applications. Emphasis is placed on synthesis methodologies, structure-property relationships, and practical applications in polymer composites and coatings, while highlighting current limitations and future research directions.

2. Micro/Nano Encapsulation Techniques

Micro- and nano-encapsulation techniques employed for self-healing applications are generally classified into physical, chemical, and physico-chemical methods based on the mechanism of capsule formation. The choice of encapsulation technique significantly influences capsule size, shell morphology, mechanical robustness, and release behavior of the healing agent, thereby affecting overall self-healing efficiency [11,12].

2.1 Physical Methods

Physical encapsulation methods rely primarily on mechanical or thermodynamic processes without involving chemical reactions for shell formation. Common techniques include spray drying, solvent evaporation, phase separation, and melt dispersion [13]. In spray drying, a solution or emulsion containing the healing agent and shell material is atomized into a heated chamber, leading to rapid solvent evaporation and capsule formation. This method is attractive due to its simplicity, scalability, and industrial compatibility; however, it often produces capsules with relatively broad size distributions and limited control over shell thickness [14].

Solvent evaporation and phase separation techniques are widely used for encapsulating liquid healing agents within polymer shells. In these methods, an oil-in-water or water-in-oil emulsion is prepared, followed by controlled solvent removal to induce polymer precipitation around the core material. Although physical methods are cost-effective and easy to implement, the resulting capsules may exhibit lower mechanical strength and reduced stability under long-term service conditions compared to chemically synthesized shells [13].

2.2 Chemical Methods

Chemical encapsulation methods rely on in situ chemical reactions to form polymeric shells around healing agent cores, offering excellent control over capsule size, shell thickness, and mechanical properties, which makes them widely used in self-healing polymer systems [15]. Common approaches include in situ polymerization, interfacial polymerization, and emulsion polymerization. Urea–formaldehyde (UF) and melamine–formaldehyde capsules formed via in situ polymerization exhibit high mechanical strength, thermal stability, and effective rupture during crack propagation [16]. Interfacial polymerization enables the formation of robust polyurethane, polyurea, and polyamide shells, while emulsion polymerization is often employed to produce PMMA shells with uniform morphology. Although chemical methods allow precise tuning of capsule characteristics, the use of toxic monomers and complex reaction conditions raises environmental and safety concerns [15,17].

Figure 1: Schematic representation of chemical encapsulation methods showing polymeric shell formation around core materials [15,16].

2.3 Physico-Chemical Methods

Physico-chemical encapsulation methods combine elements of both physical and chemical processes to form capsules with tailored properties. Coacervation, sol–gel techniques, and layer-by-layer (LbL) assembly are prominent examples [11,18]. Complex coacervation, based on electrostatic interactions between oppositely charged polymers, enables the formation of capsules with high encapsulation efficiency and relatively uniform size distribution. This method is particularly suitable for temperature-sensitive healing agents.

Sol–gel encapsulation involves the hydrolysis and condensation of inorganic precursors to form hybrid organic–inorganic shells, offering enhanced thermal and chemical stability. Layer-by-layer assembly allows precise control over shell thickness and functionality through sequential deposition of polymeric or inorganic layers, making it attractive for stimuli-responsive and multi-functional self-healing systems. Despite their versatility, physico-chemical methods may face challenges related to processing complexity and scalability [18].

- Polymer Coating Materials and Strategies

Polymer coatings are widely applied in protective, functional, and controlled-release systems. Selection of coating material and strategy depends on mechanical properties, thermal behavior, and responsiveness to stimuli. Major polymer classes used are thermoset polymers, thermoplastic polymers, and stimuli-responsive polymers.

3.1 Thermoset Polymers

Thermoset polymers are crosslinked materials that form rigid, insoluble, and heat-resistant structures upon curing. The crosslinking process creates a three-dimensional network that imparts excellent mechanical strength, chemical stability, and dimensional integrity. Common examples of thermosets include epoxy resins, polyurethane, and phenolic resins. Due to their robust properties, thermoset polymers are widely employed in protective coatings, corrosion-resistant layers, electrical insulation, adhesives, and even self-healing systems. Their inherent rigidity and resistance to deformation make them ideal for applications where durability under mechanical or chemical stress is critical. However, the irreversible crosslinking reaction also limits their reprocessability; once cured, thermosets cannot be remelted, reshaped, or recycled like thermoplastics. This characteristic necessitates careful processing and design considerations during manufacturing to ensure optimal performance. Advances in thermoset chemistry, including the development of reprocessable or partially reversible networks, are emerging to address these limitations [19].

3.2 Thermoplastic Polymers

In contrast, thermoplastic polymers are linear or slightly branched materials that soften upon heating and solidify when cooled, making them highly processable and recyclable. Common thermoplastics used in coatings include polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA). Their reversible thermal behavior allows for reshaping, extrusion, and molding into complex geometries. Thermoplastic coatings offer advantages such as flexibility, ease of fabrication, and potential for material recovery at the end of life. However, they generally exhibit lower chemical, thermal, and mechanical resistance compared to thermosets, limiting their use in highly demanding environments. Innovations in thermoplastic blends, composites, and nanofiller incorporation aim to improve their performance, particularly for protective and functional coatings [20].

3.3 Stimuli-Responsive Polymers

Stimuli-responsive or “smart” polymers are materials that undergo reversible changes in their physical or chemical properties in response to external stimuli such as temperature, pH, light, or magnetic fields. For example, poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM) exhibits thermo-responsive behavior, contracting or swelling with temperature variations, while chitosan and alginate derivatives respond to pH changes for controlled release applications. These polymers are particularly valuable for advanced coating systems, drug delivery platforms, and adaptive surfaces, where dynamic responses to environmental changes are required. By tuning the polymer composition and architecture, it is possible to achieve precise control over release rates, adhesion, permeability, and other functional properties, opening new avenues for smart material design and multifunctional coatings [21].

- Self-Healing Mechanisms Enabled by Encapsulation

Encapsulation-based self-healing strategies improve the autonomous repair of materials by storing healing agents within micro- or nano-capsules, which are released upon damage. The primary mechanisms include capsule rupture-based healing, diffusion-based healing, and multiple healing cycles.

4.1 Capsule Rupture-Based Healing

Capsule rupture-based self-healing relies on microcapsules embedded within a polymer matrix that release healing agents upon mechanical damage. When a crack propagates through the material, it ruptures the microcapsules, releasing the encapsulated agent into the damaged region. This healing agent subsequently reacts, often in the presence of a catalyst dispersed within the matrix, to polymerize and seal the crack. Commonly used systems include urea-formaldehyde or melamine-formaldehyde microcapsules filled with epoxy, polyurethane, or other reactive monomers. The primary advantage of capsule rupture mechanisms is the rapid, localized repair they provide, which can restore mechanical integrity soon after damage occurs. However, this approach is inherently single-use, as the microcapsules are consumed during the healing event. Once a capsule is depleted, the same site cannot be healed again, limiting the material’s long-term self-healing capability. Researchers have explored methods to improve capsule efficiency and optimize agent loading, ensuring that cracks encounter sufficient healing material to restore strength and prevent crack propagation [22].

4.2 Diffusion-Based Healing

Diffusion-based self-healing strategies rely on the controlled migration of healing agents from internal reservoirs, such as vascular networks, hollow fibers, or nanocapsules, into damaged regions over time. Unlike rupture-based systems, which act only at the moment of mechanical failure, diffusion mechanisms allow continuous, gradual repair and can address more extensive or distributed damage. Healing agents move through the matrix either passively, driven by concentration gradients, or actively in response to external triggers. Integration with stimuli-responsive polymers enhances this approach; for example, changes in temperature, pH, moisture, or light can accelerate or direct the diffusion process. This controlled delivery ensures that healing occurs precisely where and when it is needed, improving durability and extending the operational lifetime of the material [23].

- Multiple Healing Cycles

Single-use capsule systems are limited by their inability to repair recurrent damage. To address this, multi-capsule arrangements or interconnected microvascular networks have been developed, providing fresh healing agents for repeated healing events. In such systems, cracks can access new reservoirs, enabling multiple repair cycles and significantly prolonging the service life of the polymer. Advanced designs combine capsule and vascular strategies or exploit reversible chemistries, such as Diels–Alder reactions or supramolecular bonding, which allow healing agents to re-form after reaction. These multi-cycle systems are particularly advantageous for high-stress environments or structural applications, where damage may occur repeatedly over time. By integrating both material design and delivery architecture, researchers have created self-healing polymers capable of responding to diverse damage scenarios, making them more practical for industrial and commercial applications [24].

4.4 Comparative Overview of Self-Healing Strategies

Each self-healing approach offers unique advantages and limitations depending on the application. Capsule rupture-based systems provide fast, localized repair and are relatively simple to implement, but their single-use nature restricts long-term effectiveness. Diffusion-based mechanisms, in contrast, allow continuous or delayed healing over larger areas and can be finely tuned using stimuli-responsive polymers; however, their repair rate may be slower, and precise control over agent migration may be challenging [25]. Multi-cycle healing systems address the limitations of single-use capsules by providing repeated access to fresh healing agents, either through microvascular networks or reversible chemistries, enhancing durability and structural longevity. By carefully selecting and combining these strategies, materials can be engineered for specific operational requirements-for instance, rapid localized repair for low-damage risk environments, sustained healing for slow-degrading materials, or multiple-cycle systems for critical load-bearing applications. The ongoing development of hybrid approaches, such as integrating capsule rupture with vascular delivery or embedding smart stimuli-responsive agents, offers the potential to achieve both immediate and long-term self-healing performance, making polymers more reliable and resilient for industrial, aerospace, and biomedical applications [26].

- Applications in Polymer Composites

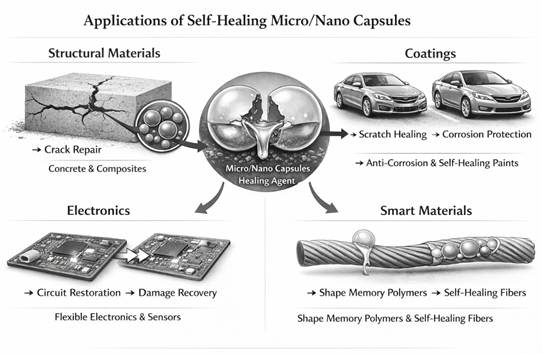

Structural Materials:

Diffusion-based self-healing is particularly valuable in structural polymer composites, where the formation of microcracks over time can severely compromise mechanical integrity and lead to premature failure. Unlike single-use capsule systems, diffusion-based mechanisms allow healing agents to gradually migrate into damaged regions, enabling continuous or repeated repair even in areas that are difficult to access. This property is especially important in aerospace, automotive, and civil engineering applications, where components are subject to cyclic loading, environmental degradation, and complex stress distributions. By maintaining the integrity of the polymer matrix, diffusion-based healing reduces the risk of crack coalescence and catastrophic failure, effectively extending the service life of high-performance materials. Advanced designs often integrate stimuli-responsive polymers, where temperature, moisture, or mechanical stress can trigger or accelerate the diffusion of healing agents, ensuring timely repair. Additionally, diffusion-based systems can be combined with fiber-reinforced composites or microvascular networks to optimize the distribution of healing agents throughout large, load-bearing structures, providing both durability and resilience in demanding operational environments [27].

Coatings:

In protective coatings, self-healing polymers play a critical role in restoring barrier properties against environmental degradation, chemical attack, corrosion, or mechanical wear. Diffusion-based mechanisms are particularly advantageous in this context, as they allow healing agents to gradually migrate into damaged or scratched regions without requiring external intervention, maintaining the continuity and integrity of the coating. This ensures that the underlying substrate remains shielded from moisture, oxygen, or corrosive agents, which is especially important in metal structures, pipelines, and marine equipment. Stimuli-responsive coatings further enhance performance by activating healing processes in response to environmental triggers such as changes in moisture, pH, temperature, or even UV exposure. For instance, pH-sensitive coatings can release corrosion inhibitors when exposed to acidic conditions, while moisture-responsive systems can accelerate polymerization to seal microcracks. Incorporating nanocapsules or microvascular networks into these coatings can improve the distribution and availability of healing agents, allowing repeated or localized repairs and prolonging the operational life of protective surfaces in harsh industrial, marine, or infrastructure environments [28].

Electronics & Smart Materials:

Self-healing polymer composites are increasingly being adopted in flexible electronics, wearable devices, sensors, and other smart materials, where mechanical integrity and consistent performance are critical. Diffusion-based healing mechanisms play a key role in these applications by allowing healing agents to migrate into microcracks or damaged regions, restoring both the structural and functional properties of the material without external intervention. This ensures that minor mechanical damages—such as bending, stretching, or accidental scratches do not disrupt electrical pathways or compromise device functionality. When combined with stimuli-responsive polymers, the self-healing process can be precisely triggered by environmental or operational signals, such as temperature changes, light exposure, or electrical currents. Such targeted healing not only repairs physical damage but also preserves conductivity, sensor sensitivity, and overall device performance. Additionally, integrating nanocapsules, conductive fillers, or microvascular networks within the polymer matrix enhances the efficiency and speed of repair, supporting long-term reliability. These diffusion-enabled, smart self-healing systems are particularly important for next-generation electronics, soft robotics, and adaptive materials, where durability, resilience, and uninterrupted functionality are essential under repeated deformation or harsh operating conditions [29].

Figure 2: Applications of Self-Healing Micro/Nano Capsules in Structural Materials, Coatings, Electronics & Smart Materials.

- Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite significant advances in micro/nano encapsulation and self-healing polymer systems, several challenges remain that limit their widespread application. One major issue is the compatibility and stability of the encapsulated agents within the polymer matrix; Premature leakage, aggregation, or chemical degradation of the core material can reduce healing efficiency and long-term performance. Achieving uniform capsule size, shell thickness, and mechanical robustness, particularly at the nanoscale, also remains difficult, directly impacting reproducibility and release kinetics. Additionally, many chemical encapsulation processes rely on toxic monomers or organic solvents, raising environmental and safety concerns. The cost and scalability of producing high-quality micro/nano capsules and self-healing polymers is another limiting factor, preventing large-scale commercialization [30].

Future developments in the field are focused on addressing these limitations. The use of biodegradable polymers, water-based systems, and non-toxic monomers can reduce environmental impact while maintaining functional performance. Integration of stimuli-responsive polymers, multi-agent encapsulation, and nanoengineered shells offers potential for more precise controlled release, repeated healing cycles, and targeted delivery. Advances in fabrication techniques, including microfluidics, 3D printing, and layer-by-layer assembly, promise improved precision, reproducibility, and scalability. Finally, combining self-healing polymers with sensing technologies, electronics, or biomedical devices could enable the development of autonomous, adaptive, and multifunctional materials, paving the way for next-generation applications in a variety of industries.

- Conclusion

Micro- and nano-encapsulation of healing agents, combined with tailored polymer coatings, represents a highly effective strategy for developing autonomous self-healing polymer systems. Physical, chemical, and physico-chemical encapsulation techniques allow precise control over capsule size, shell thickness, and release behavior, while thermoset, thermoplastic, and stimuli-responsive coatings enhance mechanical strength, environmental stability, and controlled activation of healing. Capsule rupture, diffusion-driven repair, and multi-cycle healing mechanisms demonstrate the versatility and practical applicability of these systems in polymers, composites, coatings, and biomedical materials. Despite significant progress, challenges such as material compatibility, environmental impact, scalability, and cost remain. Future research should focus on sustainable polymers, multi-functional coatings, and integration with smart and adaptive systems to achieve repeated healing, improved efficiency, and commercial viability. Overall, encapsulation-based self-healing strategies hold great promise for extending the service life and reliability of polymeric materials in diverse applications.

Acknowledgement: Rahul Patil sincerely acknowledges Kavayitri Bahinabai Chaudhari North Maharashtra University, Jalgaon, for awarding the Vice-Chancellor Research Motivation Scheme (VCRMS), which supported the research project.

References:

- White, S. R., Sottos, N. R., Geubelle, P. H., Moore, J. S., Kessler, M. R., Sriram, S. R., Viswanathan, S. (2001). Autonomic healing of polymer composites. Nature, 409(6822), 794–797. https://doi.org/10.1038/35057232.

- Polymers Special Issue. (2025). Polymer micro‑ and nanocapsules: Current status, challenges, andopportunities.Polymers.https://www.mdpi.com/journal/polymers/special_issues/Polymer_Micro_Nanocapsules.

- Nayak, S., Vaidhun, B., & Kedar, K. (2024). Applications of microcapsules in self-healing polymeric materials. Current Nanoscience, 2, 218–241.

- Zehra, S., Mobin, M., Aslam, R., & Bhat, S. u. I. (2023). Nanocontainers: A comprehensive review on their application in stimuli-responsive smart functional coatings. Progress in Organic Coatings, 176, 107389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.porgcoat.2023.107389.

- Montemor, M. F. (2024). Advanced micro/nanocapsules for self-healing coatings. Applied Sciences, 14(18), 8396. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14188396.

- Yuan, Y., et al. (2023). Self‑healing poly(urea formaldehyde) microcapsules: Synthesis and characterization. Polymers, 15(7), 1668. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15071668

- Jiang, Y., Yao, J., & Zhu, C. (2022). Improving the dispersibility of poly(urea‑formaldehyde) microcapsules for self‑healing coatings using preparation process. Journal of Renewable Materials, 10(1), 135–148. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2021.016304

- Polythiourethane microcapsules as novel self‑healing systems for epoxy coatings. (2017). Polymer Bulletin. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00289‑017‑2021‑3.

- Montemor, M. F. (2014). Functional and smart coatings for corrosion protection: A review of recent advances. Surface and Coatings Technology, 258, 17–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2014.06.031.

- Preparation and properties of melamine urea-formaldehyde microcapsules for self-healing of cementitious materials. (2017). PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28773280/.

- Zhu, Y., Ye, X., Rong, M. Z., & Zhang, M. Q. (2015). Self-healing polymeric materials based on microencapsulated healing agents: From design to preparation. Progress in Polymer Science, 49–50, 175–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2015.07.002.

- Blaiszik, B. J., Kramer, S. L. B., Olugebefola, S. C., Moore, J. S., Sottos, N. R., & White, S. R. (2010). Self-healing polymers and composites. Annual Review of Materials Research, 40, 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-matsci-070909-104532.

- Zuidema, J. M., Rivet, C. J., Gilbert, R. J., & Morrison, F. A. (2014). A review of microencapsulation techniques for self-healing materials. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 2(27), 10964–10977. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4TA00643F.

- Gharsallaoui, A., Roudaut, G., Chambin, O., Voilley, A., & Saurel, R. (2007). Applications of spray-drying in microencapsulation of food ingredients: An overview. Food Research International, 40(9), 1107–1121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2007.07.004.

- Brown, E. N., White, S. R., & Sottos, N. R. (2004). Microcapsule induced toughening in a self-healing polymer composite. Journal of Materials Science, 39(5), 1703–1710. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JMSC.0000016173.73733.dc.

- Yuan, Y. C., Rong, M. Z., & Zhang, M. Q. (2008). Preparation and characterization of microencapsulated polythiol. Polymer, 49(10), 2531–2541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2008.03.042.

- Wu, D. Y., & Meure, S. (2008). Self-healing polymeric materials: A review of recent developments. Progress in Polymer Science, 33(5), 479–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2008.02.001.

- Decher, G. (1997). Fuzzy nanoassemblies: Toward layered polymeric multicomposites. Science, 277(5330), 1232–1237. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.277.5330.1232.

- Pascault, J. P., Sautereau, H., Verdu, J., & Williams, R. J. J. (2002). Thermosetting polymers. CRC Press.

- Kumar, R., & Varadarajan, K. M. (2015). Thermoplastic polymers: Processing, properties, and applications. Polymer Reviews, 55(3), 395–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/15583724.2015.1029494.

- Qiu, Y., & Park, K. (2001). Environment-sensitive hydrogels for drug delivery. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 53(3), 321–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-409X(01)00203-0.

- Brown, E. N., Kessler, M. R., Sottos, N. R., & White, S. R. (2005). In situ poly(urea-formaldehyde) microencapsulation of dicyclopentadiene. Journal of Microencapsulation, 22(6), 619–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/02652040500413581.

- Toohey, K. S., Sottos, N. R., Lewis, J. A., Moore, J. S., & White, S. R. (2007). Self-healing materials with microvascular networks. Nature Materials, 6(8), 581–585. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat1944.

- Groves, R. M., Toohey, K. S., White, S. R., & Sottos, N. R. (2009). Vascular-based self-healing polymers. Polymer, 50(5), 1283–1290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2009.01.041.

- Liu, B., Wu, M., Du, W., Jiang, L., Li, H., Wang, L., & Ding, Q. (2023). The application of self-healing microcapsule technology in the field of cement-based materials: A review and prospect. Polymers, 15(12), 2718. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15122718.

- Amaral, A. J. R., & Pasparakis, G. (2017). Stimuli responsive self-healing polymers: gels, elastomers and membranes. Polymer Chemistry, 8, 6464–6484. https://doi.org/10.1039/c7py01386h.

- 1. Blaiszik, B. J., Kramer, S. L. B., Olugebefola, S. C., Moore, J. S., Sottos, N. R., & White, S. R. (2010). Self healing polymers and composites. Annual Review of Materials Research, 40, 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-matsci-070909-104532.

- Zhang, Y., Li, X., & Chen, Z. (2023). Self-healing polymer-based coatings: Mechanisms and applications. Polymers, 17(23), 3154. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233154.

- Choi, K., Noh, A., Kim, J., Hong, P. H., Ko, M. J., & Hong, S. W. (2023). Properties and applications of self-healing polymeric materials: A review. Polymers, 15(22), 4408. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15224408.

- Stuart, M. A. C., Huck, W. T. S., Genzer, J., Müller, M., Ober, C., Stamm, M., Sukhorukov, G. B., Szleifer, I., Tsukruk, V. V., Urban, M., Winnik, F., Zauscher, S., Luzinov, I., & Minko, S. (2010). Emerging applications of stimuli-responsive polymer materials. Nature Materials, 9(2), 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat2614.

You must be logged in to post a comment.