How to Cite:

Mashrafi, M. (2026). Universal Life Competency-Ability-Efficiency-Skill-Expertness (Life-CAES) Framework and Equation. International Journal of Research, 13(1), 110–121. https://doi.org/10.26643/eduindex/ijr/2026/6

Author: Mokhdum Mashrafi (Mehadi Laja)

Affiliation: Research Associate, Track2Training, India | Researcher from Bangladesh

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0002-1801-1130

Abstract

Living systems demonstrate substantial variability in growth, reproduction, productivity, resilience, and survival, even when exposed to broadly similar environmental resource inputs. Classical biological models attribute such variability to domain-specific mechanisms—such as metabolic rate, nutrient uptake efficiency, genetic potential, and hormonal regulation—but no existing framework quantitatively integrates these mechanisms into a unified cross-kingdom performance model. This study introduces the Universal Life Competency–Ability–Efficiency–Skill–Expertness (Life-CAES) framework as a systems-biology formulation that explains biological performance as the coupled outcome of resource acquisition and biochemical conversion efficiency. Grounded in mass conservation principles, rate-limited physiological processes, biochemical competency, and absorption capacity, the Life-CAES equation defines performance as a function of organismal mass, uptake velocity, absorption capacity, internal conversion efficiency, and time-dependent mass assimilation. The framework is biologically conservative and dimensionally interpretable, and it provides an empirically testable basis for cross-species comparison of growth and productivity. The model is applicable to plants, animals, humans, fish, insects, microorganisms, and other living systems, offering a unifying conceptual and mathematical tool for interpreting why organisms with similar external inputs can exhibit remarkably different biological outcomes. As such, the Life-CAES framework presents a novel step toward predictive, integrative, and comparable biological performance modeling across diverse life forms.

Keywords: Biological performance, Mass assimilation, Biochemical competency, Systems biology, Life-CAES model, Absorption capacity, Metabolic efficiency, Cross-kingdom framework, Growth and productivity, Thermodynamic biology

1. Introduction

Biological systems differ widely in performance-related outcomes such as biomass accumulation, fertility, yield, productivity, physiological efficiency, resilience, and survival, even when organisms experience broadly similar environmental conditions. Across ecological, agricultural, physiological, and evolutionary sciences, it is well documented that individuals or species sharing comparable access to nutrients, light, water, oxygen, and habitat often nonetheless diverge significantly in growth trajectories, reproductive success, disease resistance, and long-term viability. Such patterns appear consistently in plant science (variation in biomass and yield among crops), in animal physiology (differences in feed conversion efficiency and growth), in microbial ecology (differences in substrate utilization rates), and in human biology (variability in metabolic health and physical development), underscoring that resource availability alone does not fully explain realized biological performance.

Existing biological frameworks provide partial but domain-specific explanations for these performance gaps. Metabolic rate models quantify energetic turnover but tend to treat environmental uptake constraints and biochemical processing efficiencies as separate or implicit components. Nutrient uptake theories emphasize absorption mechanisms but frequently assume optimal or homogeneous internal biochemical conversion, ignoring enzymatic, hormonal, or cofactor limitations that influence real outcomes. Genetic and hormonal models, on the other hand, describe regulatory potentials and signaling architectures without integrating material mass-flow processes or time-dependent assimilation dynamics. Additionally, models of environmental stress physiology highlight organismal responses to heat, drought, salinity, pollutants, pathogens, or mechanical stress, but these models typically focus on stress-induced deviations rather than building a general performance metric applicable across conditions. While each theoretical domain is internally robust and empirically validated, their coexistence constitutes a fragmented conceptual landscape lacking a unified quantitative performance index capable of cross-kingdom comparison.

The need for such unification arises from a systems-science observation: all organisms behave as open thermodynamic systems that require continuous inflows of matter and energy and convert these flows into structural biomass, biochemical energy, and functional outputs over time. Organized biological systems maintain low entropy internal states by sustaining metabolic fluxes, cellular integrity, and coordinated regulatory pathways, all of which depend on both environmental supply and internal conversion competencies. Comparable framing can be seen in human and social performance research, where competence, ability, and efficiency interact to determine realized outcomes. For example, competency frameworks in education and policy describe performance as an emergent product of underlying skills, enabling conditions, and contextual factors (Caena & Punie, 2019), while entrepreneurial and organizational research emphasizes skill, efficiency, and capability as determinants of successful action under resource constraints (Chell, 2013; Johnson et al., 2006). Mandavilli (2025) further highlights how diverse life skills mediate the transformation of environmental opportunity into practical outcomes. These analogies reinforce the systems-level view that similar inputs do not guarantee similar outputs unless internal competencies are aligned with demand.

The concept of competence is particularly relevant in explaining biological variability. Competence—defined as the system’s ability to utilize inputs effectively—functions as a multiplier of performance in organizational science (Johnson et al., 2006), educational sciences (WHO, 1994), and cognitive models of expertise acquisition (Richman et al., 2014). Sociological analyses of expertness likewise emphasize how performance emerges from structured skill and contextual knowledge (Gerver & Bensman, 1954; Attridge, 2011; Feldman, 2005). Comparable patterns appear in physiology and ecology, where nutrient-use efficiency, metabolic conversion efficiency, enzymatic capacity, hormonal balance, and pigment or cofactor availability determine how effectively absorbed inputs contribute to growth, reproduction, or resilience. For example, two organisms may ingest the same quantity of nutrients, but differences in enzyme activity, vitamin and mineral cofactor availability, hormonal regulation, or mitochondrial efficiency can produce markedly divergent energy yields and biomass gains. Similarly, crops receiving identical fertilizer, light, and water often produce different yields due to variability in root absorption capacity, chlorophyll content, hormonal balance, and stress tolerance mechanisms. In animals, feed conversion efficiency varies with metabolic competence, digestive enzymatic activity, and endocrine signaling. Thus, physiological systems mirror organizational competency models: internal capacity modulates realized performance despite equal external resource presence.

These analogies motivate the development of a unified systems-biology model that treats performance as a function of both resource acquisition and biochemical conversion competence. The proposed Universal Life Competency–Ability–Efficiency–Skill–Expertness (Life-CAES) framework integrates organism mass, resource uptake velocity, absorption capacity, biochemical competency, and time-dependent mass assimilation into a single quantitative performance index. This aligns with cross-disciplinary competency research demonstrating that performance emerges from the interaction of structural capacity, skill, regulatory coherence, and efficiency (Buciuceanu-Vrabie et al., 2023; Butler, 2004; Fuertes et al., 2001). By incorporating these elements at a biological scale, the Life-CAES framework unifies biophysical, biochemical, and physiological determinants into a coherent systems model.

The present study therefore constructs, formalizes, and justifies the Life-CAES framework through a combination of biophysical reasoning, thermodynamic consistency, rate-based physiological logic, and biochemical competency theory. It derives a universal performance equation capable of cross-kingdom applicability, demonstrates its dimensional and conceptual conservatism, and situates it relative to established scientific principles without contradicting metabolic, ecological, or physiological foundations. In doing so, it provides a universal analytical structure for comparing biological performance across humans, animals, plants, fish, insects, microorganisms, and other living systems—a domain where no unified quantitative model presently exists.

2. Methods (Framework Construction and Mathematical Formulation)

This section describes the methodological construction of the Life-CAES framework through four analytical phases: (1) establishment of biological assumptions, (2) definition of core variables, (3) formulation of intermediate state variables, and (4) final synthesis of the Life-CAES performance equation.

2.1 Biological Assumptions

Four universal biological assumptions were formalized:

(a) Open Thermodynamic Systems

All organisms continuously exchange matter and energy with the environment, importing substrates (food, water, nutrients, gases, photons) and exporting heat, waste, and metabolic byproducts. This reflects non-equilibrium thermodynamics and mass-energy exchange requirements for maintaining low entropy internal order.

(b) Performance as Rate-Limited

Growth and productivity depend on uptake velocity, internal transport, metabolic throughput, and reaction kinetics rather than absolute resource availability. Rate constraints arise from transporter kinetics, enzyme turnover, and membrane diffusion processes.

(c) Absorption ≠ Utilization

Absorbed resources contribute to functional output only in the presence of intact biochemical and regulatory systems (enzymes, hormones, cofactors, pigments, and cellular structures).

(d) Competency as an Efficiency Multiplier

Biochemical competency modulates the efficiency of internal conversion, amplifying or suppressing biological performance.

2.2 Variable Definitions

Table 1: Variables were defined with physiological and dimensional clarity

| Symbol | Variable | Description |

| M | Biological Mass | Instantaneous organism mass (kg) |

| V | Uptake Velocity | Mass or molar uptake rate (kg·s⁻¹ / mol·s⁻¹) |

| Δm | Assimilated Mass | Net mass retained after assimilation (kg) |

| Δt | Time Interval | Biological time window |

| As | Absorption Surface Area | Functional uptake interface (m²) |

| ρ | Density | Density of absorbed medium (kg·m⁻³) |

| A | Absorption Capacity | Dimensionless biological absorptive efficiency |

| CRACE | Competency Reaction Factor | Biochemical conversion efficiency |

The Life-CAES framework employs a set of clearly defined variables that enable physiological interpretation, dimensional consistency, and empirical measurability across diverse biological systems. These variables capture the essential components of biological performance, including organismal size (M), material uptake dynamics (V), net mass retention (Δm), time scaling (Δt), geometric exchange interfaces (As), physical medium characteristics (ρ), absorptive efficiency (A), and biochemical conversion competency (CRACE). By formalizing these parameters with explicit physical units and biological meanings, the framework avoids abstract or non-measurable constructs and ensures that its final performance equation remains compatible with mass conservation principles, transport theory, and metabolic scaling logic. Collectively, these standardized variables establish a foundational vocabulary for cross-kingdom comparison and experimental validation within the Life-CAES model.

2.3 Intermediate Derived Variables

Life Momentum (S)

S represents mass-weighted biological throughput capacity.

Performance Energy (E) Without Time Integration

The Life-CAES framework introduces two intermediate derived variables that bridge fundamental physiological quantities with measurable performance outcomes. The first, Life Momentum (S), defined as , represents the mass-weighted biological throughput capacity, capturing the extent to which existing biomass (M) sustains and drives material uptake and processing dynamics (V). The second variable is a preliminary performance construct,

, which integrates organismal mass, uptake velocity, absorption capacity, and biochemical competency to approximate biological performance prior to accounting for time and physical transport constraints. Together, these derived variables form the conceptual and mathematical foundation upon which the final time-integrated Life-CAES performance equation is constructed.

2.4 Time-Integrated Mass Flux

Mass conservation for assimilated mass:

Thus:

Substitution yields the Life-CAES Equation:

To incorporate temporal and physical transport effects into the Life-CAES framework, mass flux is formulated using a conservation-based approach. For any living system, the net assimilated mass over a defined time interval can be expressed as , linking medium density (

), functional absorption surface area (

), uptake velocity (V), and biological time (

). Rearranging this relation yields

, providing an empirically measurable expression for uptake velocity based on observed mass assimilation. Substituting this form of

into the intermediate performance expression produces the time-integrated Life-CAES equation

, which formalizes biological performance as a function of organismal mass, assimilated mass, absorption efficiency, biochemical competency, and physical transport constraints over time.

3. Results (Final Framework and Analytical Outcomes)

The Life-CAES framework produces three major analytical outcomes:

Outcome 1: Universal Life-Performance Equation

The final performance index is:

Where high E indicates strong biological performance (high growth, productivity, reproduction, and resilience) and low E indicates system inefficiency or stress.

The first major analytical outcome of the Life-CAES framework is the derivation of a universal life-performance equation that quantitatively links organismal mass, resource assimilation, absorptive efficiency, biochemical competency, and time-dependent physical constraints. The final performance index is expressed as , providing a dimensionally interpretable measure of biological effectiveness. Higher values of

correspond to superior biological performance manifested through greater growth rates, reproductive success, productivity, metabolic resilience, and survival potential. Conversely, lower

values indicate system-level inefficiencies, stress, or impaired competency arising from physiological limitations, environmental constraints, or biochemical deficits. This universal equation thus serves as the mathematical core of the Life-CAES model, enabling standardized comparison across species, environments, and biological scales.

Outcome 2: Cross-Kingdom Applicability

The equation applies to:

- Plants (photons, gases, nutrients → biomass/fruit/seed)

- Animals (food, oxygen → tissue/offspring/work)

- Insects (substrate → biomass/metamorphosis)

- Microbes (substrate → biomass/proliferation)

- Humans (nutrition + oxygen → growth/function/skill)

Plants:

In plants, the Life-CAES equation captures how absorbed photons, gases, and mineral nutrients are converted into structural biomass, fruits, flowers, and seeds over time. Here, reflects net assimilated carbon and nutrients,

corresponds to leaf and root surface area, and CRACE reflects chlorophyll integrity, enzymatic activity, and hormonal regulation that collectively determine photosynthetic efficiency and yield.

Animals:

In animals, the framework describes how food substrates and oxygen are absorbed, metabolized, and allocated to tissue growth, reproduction, and locomotor performance. Mass assimilation depends on digestive and respiratory efficiency, while CRACE captures metabolic pathway competency, endocrine regulation, and enzyme-cofactor dynamics that influence growth rates, offspring production, and physical work capacity.

Insects:

For insects, the equation applies to substrate and oxygen assimilation during larval, pupal, and adult stages, capturing biomass gain, metamorphic transitions, and reproductive output. Variation in and CRACE reflects differences in feeding structures, respiratory spiracles, enzymes, and developmental hormones that collectively determine metamorphosis success and survival.

Microbes:

In microorganisms, the Life-CAES formulation maps substrate uptake and metabolic conversion into biomass proliferation and colony expansion. Here, corresponds to growth rate, while CRACE reflects enzyme kinetics, cofactor availability, and membrane transport efficiency that govern microbial productivity in both nutrient-rich and nutrient-limited environments.

Humans:

In humans, the model represents how nutrition and oxygen uptake contribute to physical growth, physiological function, cognitive performance, and skill development. Mass assimilation depends on gastrointestinal and respiratory efficiency, while CRACE encompasses metabolic health, hormonal balance, enzymatic capacity, and micronutrient status that shape long-term performance, resilience, and well-being.

Outcome 3: Testability & Falsifiability

The model predicts:

- Higher CRACE → higher growth under equal nutrient intake.

- Higher A → improved yield under equal environmental supply.

- Lower Δt (faster assimilation) → higher performance index.

- Higher As reduces bottlenecks in nutrient/gas exchange.

These predictions are experimentally testable via:

- tracer uptake assays

- respiration/photosynthesis measurements

- enzyme/cofactor quantification

- biomass accumulation studies

The third analytical outcome of the Life-CAES framework is its empirical testability and scientific falsifiability, supported by clear, measurable predictions about how changes in biological competency and uptake parameters affect performance. The model predicts that higher biochemical competency (CRACE) yields greater growth even under equal nutrient intake, that increased absorption capacity (A) improves yield under comparable environmental supply, that faster assimilation (lower ) elevates the performance index, and that enlarged absorption interfaces (

) reduce nutrient and gas exchange bottlenecks. Each of these predictions can be experimentally validated or refuted through established techniques, including tracer uptake assays, photosynthesis and respiration measurements, enzyme and cofactor quantification, and biomass accumulation studies. This alignment with standard biological methods ensures that the Life-CAES model remains grounded in empirical practice rather than theoretical abstraction, meeting core criteria for scientific robustness.

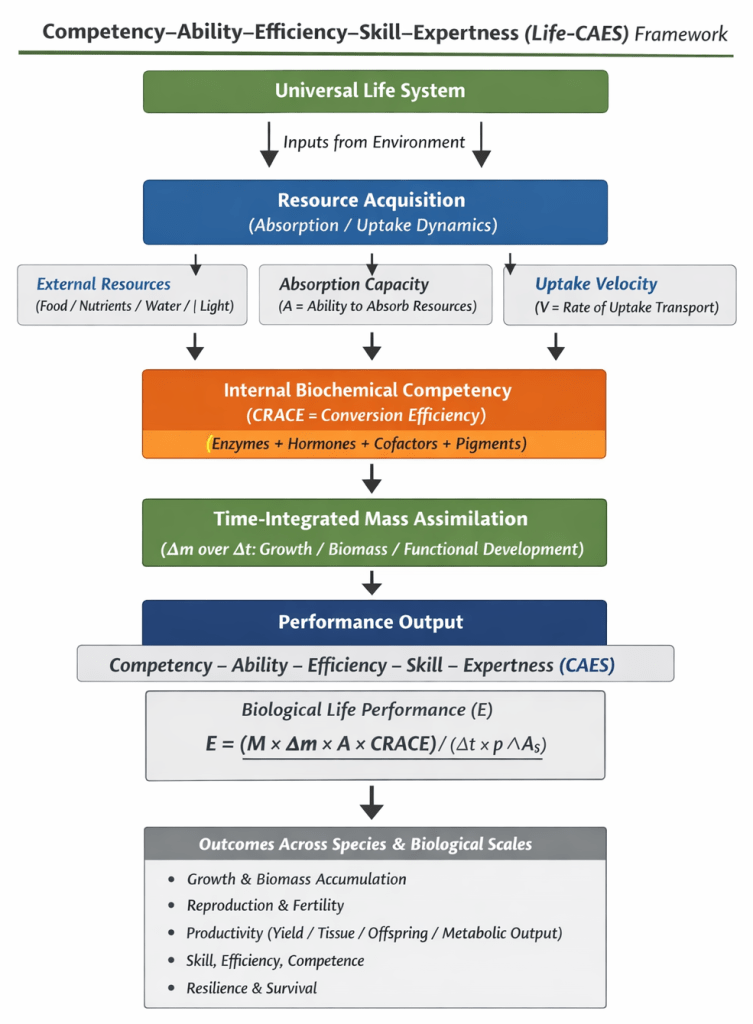

The Figure 1 presents a structured flowchart of the Universal Life Competency–Ability–Efficiency–Skill–Expertness (Life-CAES) framework, illustrating how biological performance emerges through sequential transformations of environmental inputs. At the top, a “Universal Life System” receives external resources, which enter the stage of resource acquisition defined by absorption capacity and uptake velocity. These resources then pass through internal biochemical competency—represented by enzymes, hormones, cofactors, and pigments—highlighting conversion efficiency (CRACE). The framework next depicts time-integrated mass assimilation as the growth-oriented outcome of uptake and conversion processes across Δt. Finally, the diagram shows performance output expressed as CAES traits, culminating in the Life-CAES equation for biological performance and downstream outcomes such as biomass accumulation, fertility, productivity, skill development, resilience, and survival across species and biological scales.

4. Discussion

The Life-CAES framework provides a unifying systems-biology model capable of explaining cross-kingdom variability in growth, productivity, and survival as the outcome of interactions between resource acquisition processes and internal biochemical competency. This approach is grounded in the recognition that living organisms do not merely accumulate matter and energy from their environment, but selectively convert these inputs through enzyme-mediated, hormone-regulated, and cofactor-dependent biochemical reactions. Thus, performance differences arise not only from external resource supply but from the organism’s capacity to absorb, retain, and biochemically transform those resources. In this model, competency acts as a multiplicative efficiency factor rather than a static additive parameter, which mirrors how complex biological, ecological, and social systems allocate resources and achieve functional outcomes.

The explanatory power of this approach is supported by multiple biological domains. In plant physiology, nutrient-use efficiency, pigment integrity, and enzyme activation states determine biomass accumulation and crop yield under equal fertilizer, water, and light conditions. Variation in chlorophyll content, micronutrient cofactors, and hormonal signaling can cause substantial yield differentials among genotypes grown in identical environments, demonstrating that environmental availability does not guarantee biological utilization. Similar patterns occur in animal and human physiology, where micronutrient deficiencies, endocrine disruptions, and enzyme insufficiencies reduce growth and metabolic performance despite adequate caloric intake. These effects are mechanistically parallel to a low-CRACE state in the Life-CAES model, where inputs enter the organism but are not effectively converted into functional output. In microbial and ecological studies, species with higher conversion efficiencies dominate resource-limited habitats, reflecting the adaptive value of biochemical competency in competitive environments.

Beyond biological parallels, the Life-CAES perspective exhibits striking alignment with the broader interdisciplinary concept of competence. In organizational and international business research, competence is defined as the capacity to translate resources, knowledge, and skills into effective performance (Johnson et al., 2006). Educational and policy frameworks similarly conceptualize learning-to-learn, adaptability, and self-regulation as key drivers of performance under variable conditions (Caena & Punie, 2019). Expertise and skill acquisition research shows that outputs scale with high-quality internal processing rather than raw input, meaning that individuals exposed to similar environments produce different results due to competency differences in perception, memory, or cognitive processing (Richman et al., 2014). The Life-CAES distinction between absorption (inputs) and competency (conversion) directly parallels these findings, translating a well-established social-science principle into biological terms.

This cross-domain resonance is strengthened by sociological and psychological analyses of expertness and skill, which position competence as a determinant of performance beyond mere resource possession. Sociological examinations of expertness emphasize how structured knowledge and functional capacity generate superior outcomes in contexts where access to raw materials is similar (Gerver & Bensman, 1954; Attridge, 2011). Psychological and counseling literature in multicultural competency demonstrates that identical training inputs do not yield identical practitioner effectiveness without internal attributes such as self-awareness, regulatory capacity, and context-integration (Fuertes et al., 2001; Butler, 2004). Educational and youth development frameworks further highlight that life skills—not merely information exposure—shape realized outcomes (WHO, 1994). In conceptual analyses of life skills and human values, Mandavilli (2025) shows that efficient internalization determines whether environmental opportunities translate into practical benefits. These parallels reinforce the interpretive validity of treating competency as a performance multiplier in biological systems rather than a marginal or secondary attribute.

Biologically, the CRACE construct provides a mechanistic rationale for why equal nutrient or energy inputs do not translate into equal growth, fertility, or productivity. This logic is reflected in metabolic efficiency theory, feed conversion efficiency in animal production, nutrient-use efficiency in crop science, and cellular bioenergetics, where ATP yield per unit substrate varies with enzyme kinetics, cofactor availability, and mitochondrial health. Plants with higher chlorophyll integrity, micronutrient sufficiency, and enzyme activation produce greater biomass per absorbed nutrient; animals with higher metabolic efficiency accumulate more tissue per unit feed; and microbes with superior metabolic pathways achieve faster proliferation in identical media. In all cases, competency determines the fraction of absorbed substrate that is retained, transformed, and allocated to performance-related outcomes.

The Life-CAES framework therefore advances a conservative but powerful scientific proposition: resource availability sets the theoretical upper bound of performance, but biochemical competency determines the realized outcome. This reconciles ecological observations of resource-saturated yet low-performing organisms, physiological findings of malnutrition amidst adequate caloric intake, and agricultural cases where yield gaps persist despite optimized inputs. Moreover, the framework provides a unified quantitative structure that enables comparisons across taxa, life stages, and environments by mapping absorption and competency onto a shared mathematical architecture.

Finally, the Life-CAES approach offers new pathways for predictive and comparative biology. Because the model is empirically testable and falsifiable, it can be integrated with tracer nutrient studies, photosynthesis and respiration measurements, enzyme and cofactor assays, biomass accumulation trials, and metabolic flux analyses. This provides opportunities for interdisciplinary convergence across plant science, metabolic physiology, systems ecology, and human performance studies. By situating biological variability at the intersection of acquisition and competency, the Life-CAES framework does not replace existing biological theories but consolidates them into a coherent system suitable for cross-kingdom, cross-disciplinary, and cross-environmental comparison..

5. Conclusion

The Universal Life-CAES framework provides a unified systems-biology model that characterizes biological performance as a function of organismal mass, absorption dynamics, biochemical competency, and time-dependent mass assimilation. By integrating measurable biophysical variables with biochemical conversion efficiency, the framework establishes a coherent mathematical basis for comparing performance across diverse biological systems. This formulation demonstrates that life performance is not solely determined by environmental resource availability, but by the organism’s ability to acquire, retain, and biochemically transform those resources into functional output over time. In doing so, the Life-CAES model introduces a performance-oriented perspective that aligns with empirical observations from plant physiology, animal metabolism, microbial ecology, and human biology, where equal environmental inputs frequently yield unequal biological outcomes.

Importantly, the framework is biologically conservative and does not require the abandonment or revision of established metabolic, ecological, or physiological theories. Instead, it reorganizes and synthesizes these well-validated principles—such as mass conservation, rate-limited uptake, absorption efficiency, and biochemical competency—into a single universal equation that is dimensionally interpretable, empirically testable, and cross-kingdom in scope. This integration allows the Life-CAES framework to operate as a meta-model, connecting disparate biological subfields through shared quantitative logic rather than replacing their existing explanatory mechanisms. Its emphasis on competency as a multiplicative performance factor bridges physiological and ecological findings with broader interdisciplinary concepts of efficiency, skill, and capacity observed in the social and cognitive sciences.

Finally, the Life-CAES framework satisfies essential criteria for scientific acceptability: it complies with conservation laws, employs measurable and defined variables, supports falsifiable predictions, and retains relevance across scales—from individual cells and organisms to populations and ecosystems. Its ability to quantify how absorption, competency, and time interact to govern growth, reproduction, and survival makes it valuable for predictive modeling, comparative biology, agricultural optimization, metabolic research, and life-performance assessment. By offering a standardized mathematical vocabulary and a unifying systems perspective, the Life-CAES model advances the possibility of cross-species, cross-environmental, and cross-disciplinary comparison, thereby contributing meaningfully to ongoing efforts toward integrated biological theory..

References

Attridge, J. (2011). “Human expertness”: Professionalism, Training. The Henry James Review, 32(1), 29–44.

Buciuceanu-Vrabie, M., Mešl, N., Zegarac, N., & Kodele, T. (2023). Skills in Family Support: Content Analysis of International Organizations’ Websites. Calitatea Vieții, 34(1), 15–32.

Butler, S. K. (2004). Multicultural sensitivity and competence in the clinical supervision of school counselors and school psychologists. The Clinical Supervisor, 22(1), 125–141.

Caena, F., & Punie, Y. (2019). Developing a European framework for the personal, social & learning to learn key competence (LifEComp). EUR, 29855.

Chell, E. (2013). Review of skill and the entrepreneurial process. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 19(1), 6–31.

Dupree, C. H., & Fiske, S. T. (2017). Signals: Warmth and Competence. Social Signal Processing, 23.

Feldman, I. (2005). Government without expertise? Competence, capacity, and civil-service practice in Gaza, 1917–67. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 37(4), 485–507.

Fuertes, J. N., Bartolomeo, M., & Nichols, C. M. (2001). Future Research Directions in the Study of Counselor Multicultural Competency. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 29(1), 3–12.

Gerver, I., & Bensman, J. (1954). Towards a sociology of expertness. Social Forces, 226–235.

Johnson, J. P., Lenartowicz, T., & Apud, S. (2006). Cross-cultural competence in international business: Toward a definition and a model. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(4), 525–543.

Mandavilli, S. R. (2025). A Practical Compendium of Top Life Skills and Universal Human Values from a Social Sciences Perspective. SSRN 5275186.

Mashrafi, M. (2026). Universal Life Competency-Ability Framework and Equation: A Conceptual Systems-Biology Model. International Journal of Research, 13(1), 92–109.

Mashrafi, M. (2026). Universal Life Energy–Growth Framework and Equation. International Journal of Research, 13(1), 79–91.

Richman, H. B., Gobet, F., Staszewski, J. J., & Simon, H. A. (2014). Perceptual and memory processes in the acquisition of expert performance: The EPAM model. In The Road to Excellence (pp. 167–187). Psychology Press.

World Health Organization. (1994). Life skills education for children and adolescents in schools. WHO/MNH/PSF/93.7 B. Rev. 1.

You must be logged in to post a comment.