Introduction

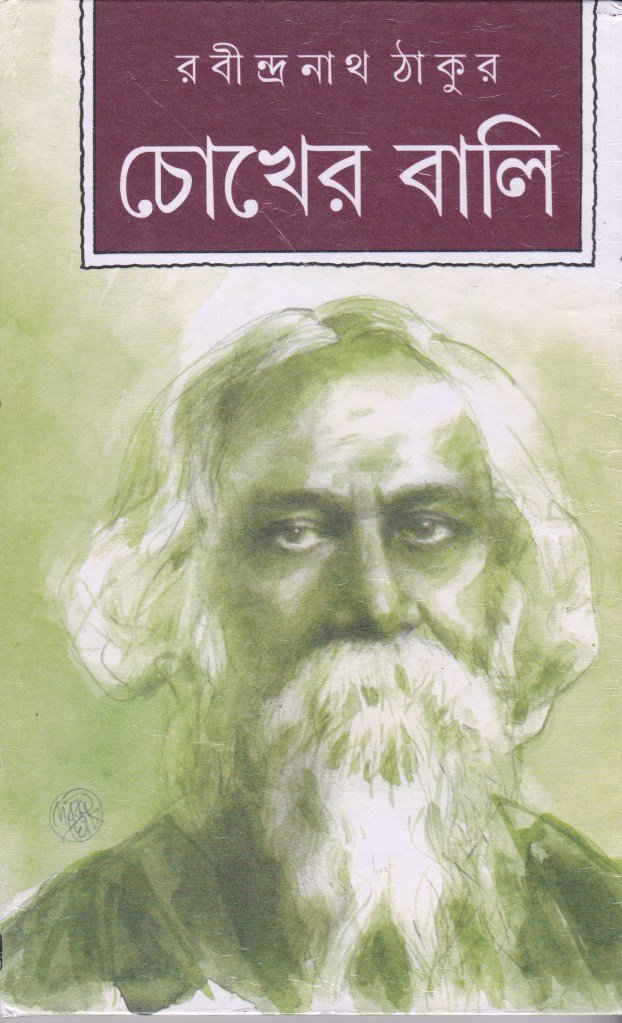

Rabindranath Tagore’s 1903 Bengali novel Chokher Bali is often referred to as India’s first modern novel, where he highlighted the issues of women’s education, child marriage and the treatment of widows in 19th and 20th century Bengal. It was first serialised in the Bengali literary magazine, Bangadarshan first founded in 1872 by Bankim Chanra Chattopodhay and later resuscitated under the editorship of Tagore in 1901.

About The Author

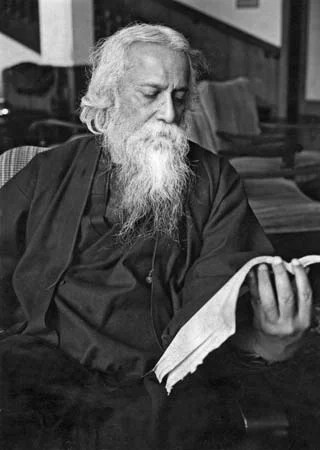

Rabindranath Tagore (7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941) was a Bengali Polymath —poet, writer, playwright, composer, philosopher, social reformer and painter. He reshaped Bengali Literature and music as well as Indian Art with Contextual Modernism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Author of the “profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful” poetry of Gitanjali, he became in 1913 the first non-European and the first lyricist to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Tagore’s poetic songs were viewed as spiritual and mercurial; however, his “elegant prose and magical poetry” remain largely unknown outside Bengal. He was a fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society. Referred to as “the Bard of Bengal”, Tagore was known by sobriquet: Gurudev, Kobiguru, Biswakobi.

Storyline of The Novel

The plot revolves around four protagonists- Mahendra, Ashalata, Binodini and Bihari. Mahendra is the only scion of a rich family based in Calcutta. Bihari is his childhood friend, who frequents his house. Mahendra’s mother wanted him to marry Binodini, her friend’s daughter. But Mahendra refused. Then his mother requested Bihari to marry Binodini and save the poor girl which Bihari refused. Eventually, Binodini got married to a man who died soon after marriage. Meanwhile, Mahendra married Ashalata, a poor orphan girl. Mahendra was besotted with his wife when Binodini came to live in their house. With time, an extra-marital relationship develops between Mahendra and Binodini, which threatens to destroy his marriage with Ashalata. But soon Binodini discovers that Mahendra is a self-obsessed person, unable to provide a safe shelter to her. So she inclines towards Bihari, who lives life by principles. Throughout the novel, there is an implicit implication of Bihari’s affection towards Ashalata, though he never crosses the boundaries of the relationship. In the end, Bihari falls in love with Binodini when realizes her feelings for him. He proposed to marry her, which Binodini refused saying that she doesn’t want to ‘dishonour’ him further. During that period (the novel was written in 1902), widow remarriage was not well accepted in society. That may partially explain the reason behind Binodini’s refusal. In the end, Binodini leaves for Varanasi– a fate that awaited most of the widows in those days.

Analysis of The Storyline

The term ‘Chokher Bali’ literally means a sand grain in eye in Bengali and metaphorically means to be a source of irritation or disturbance in someone’s eyes, which is what Asha and Binodini become for each other. Binodini is presented in many avatars a hopeless widow, a friend, a temptress, and a remorseful woman. Tagore gives readers an insight into her desires and longings, the feeling that many widows at the time had silently undergone. On the other hand, Asha is presented as naive and innocent, which combined with her illiteracy initially results in her subjugation. The narrative almost becomes an implicit debate on love and morality, urging readers to understand Asha and Binodini outside of the social norms of Bengali society. The central character Binodini is not an idealised Indian woman but a woman with shades of grey and very human flaws. Binodini cannot come to terms with her life as a widow, as she is still young and has wants and desires. She feels wronged as she believes she is superior to Asha in all respect and deserves the life she is living. Tagore’s depiction of Binodini is impressive as she subverts the expectation of society for widows to forgo all worldly desires.

Criticism of The Storyline

The story of this novel delves deep into many facets of human relationships and how a single wrong decision can make the life disharmonious. Jealousy and deprivation of happiness can result into an emotion strong enough to forget all other ties and relationships.Tagore shows the intellectual interchange between the characters, possible due to education and the interception of letters. The innocent and illiterate child bride Asha fails to understand the exploitation she faces at the hands of her husband and dear Bali (Binodini) whom she trusted blindly. Tagore does not justify Binodini’s actions and actually is sympathetic to Asha, perhaps stressing that Asha would have been able to avoid Binodini’s interference in her marital life, if she were educated enough to understand the intentions behind her friendly nature. However, one of Tagore’s greatest regrets in the novel is the ending. Despite his progressive portrayal of Binodini and Bihar, he does not allow them to marry at the end. Although, today we may see the girl marrying the guy as regressive today in Tagore’s time a widowed woman was not permitted to re-marry. Thus, ending the novel with Binodini and Bihari marrying would have been the most revolutionary.

Movie Adaptation of The Novel

Adapted from Tagore’s Chokher Bali, the movie with the same name was released in 2003, directed by eminent Bengali Moviemaker Rituparno Ghosh, starring Aishwarya Rai Bachhan, Raima Sen, Prosenjit Chatterjee and Tota Roy Choudhury in the lead roles. The movie won the National Film Award for Best Feature Film in Bengali and was nominated for the Golden Leopard Best Film award at the Locarno International Film Festival in 2003. Aishwarya Rai won the Best Actress award at the Anandalok Awards 2003.

Conclusion

A century after Chokher Bali, education is still a struggle for many women to access easily globally. Tagore’s novel is radical and unconventional presenting a viewpoint that is ahead of the conservative times of 19th and 20th century India. Through the story of Binodini, Tagore questions the societal norms. He condemns all kinds of taboos and unjust customs which deprive women and especially widows of their rightful freedom and autonomy; confined to live a mournful colourless life. As a man from a privileged background, his understanding of the emotions of Indian women and his empathetic attitude towards them is remarkable.

You must be logged in to post a comment.