Introduction

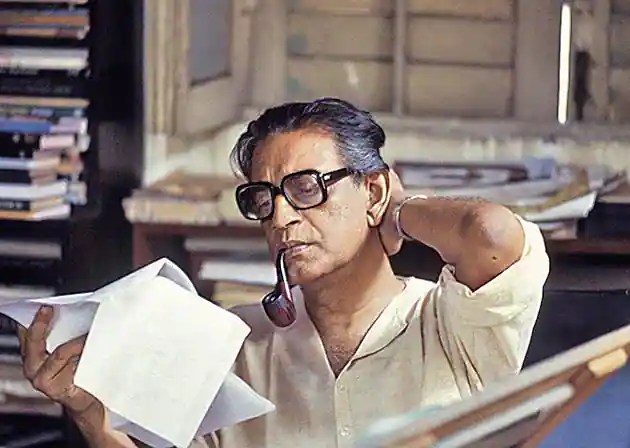

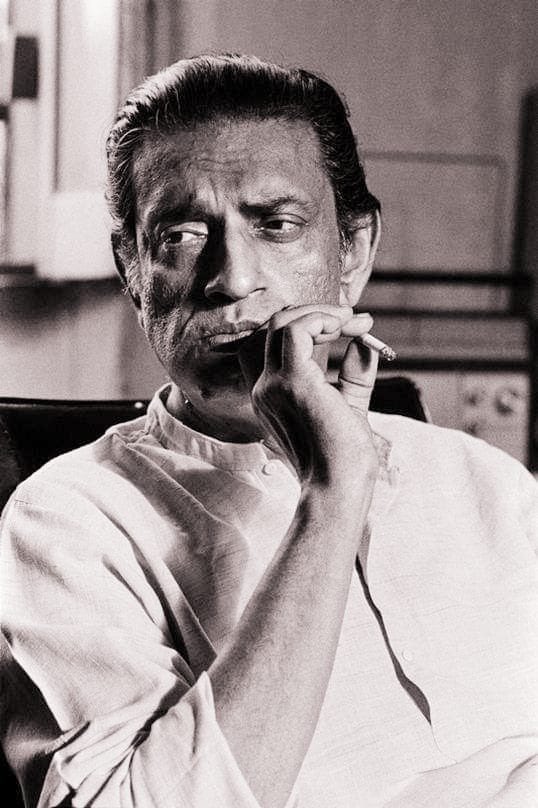

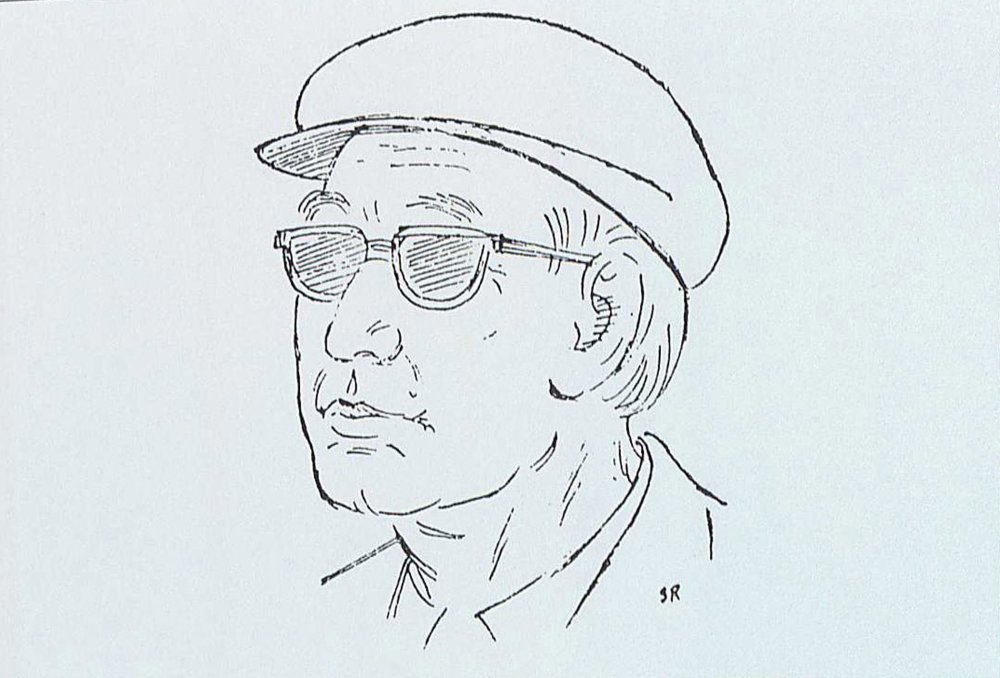

Satyajit Ray was India’s first internationally recognized film-maker and, several years after his death, still remains the most well-known Indian director on the world stage. Ray has written that he became captivated by the cinema as a young college student, and he was self-taught, his film education consisting largely of repeated viewings of film classics by de Sica, Fellini, John Ford, Orson Welles, and other eminent directors.

Early Life and Family Background

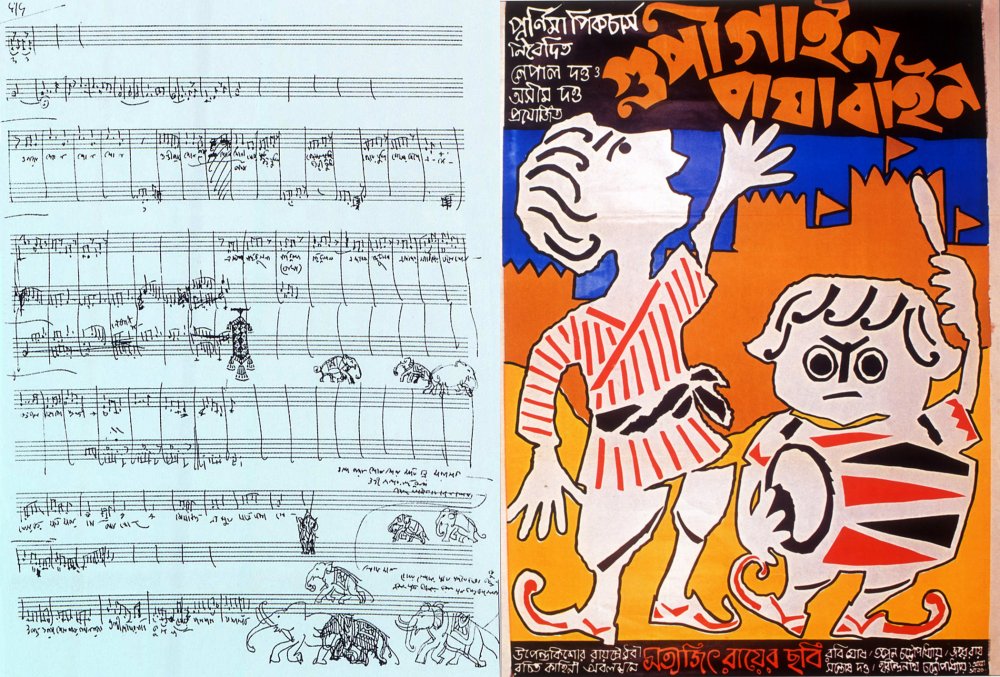

Satyajit Ray was born into an illustrious family in Kolkata (then Calcutta) on 2nd May,1921. His grandfather, Upendra Kishore Ray-Chaudhary, was a publisher, illustrator, musician, the creator of children’s literature in Bengali and a leader of the Brahmo Samaj, a religious and social movement in nineteenth century Bengal. His father, Sukumar Ray, was a noted satirist and India’s first writer of nonsensical rhymes, akin to the nonsense verse of Edward Lear. Having studied at Ballygunge Government High School, Calcutta and completed his BA in economics at Presidency College, Satyajit Ray went on to develop an interest in fine arts. Later in life, Satyajit Ray made a documentary of his father’s life. His film, Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne, was based on a story published by his grandfather in 1914, but even other films, such as Hirok Rajah Deshe, “The Kingdom of Diamonds”, clearly drew upon his interest in children’s poetry and nonsensical rhymes.

The Crisis of Indian Cinema Before Ray

From the 1920s to the early 1950s, several directors working within Hollywood—as well as filmmakers in former Soviet Union, France, Italy, Germany, and Japan—considered cinema not as a mere tool of entertainment but as a medium for creative expression. Filmmakers such as Charlie Chaplin, Sergei Eisenstein, Jean Renoir, Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica, Akira Kurosawa, and others deployed artistically innovative filmic devices to convey profound statements about the complexities of life. Some of the aesthetically satisfying films produced during this period were hailed as cinematic masterpieces. Films in India, however, prioritised cliched elements such as sentimental slush, ersatz emotion, theatricality, romantic tales, spectacle-like songs, and happy endings in these decades. Instead of making serious attempts at formal experimentation, Indian directors continued catering to the lowest common denominator audience.

Breakthrough of Satyajit Ray

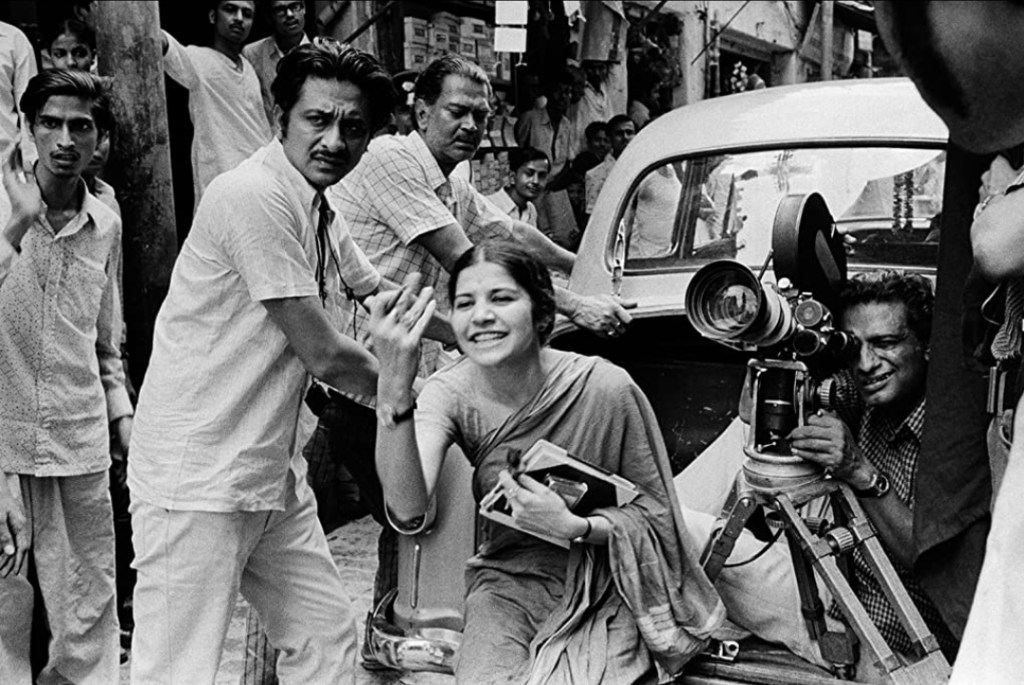

A young Ray had grown up on Hollywood movies, so when his ad agency sent him to London for higher training, he spent more and more of his time in the company of films and started “losing interest in advertising in the process,” he once said in an interview. During this trip, he saw Vittorio De Sica’s “Ladri di biciclette” (Bicycle Thieves),in 1948, a neo-realist Italian masterpiece of post-War despair and was entranced by its beguiling simplicity and humanism. Back in Calcutta, he heard that Jean Renoir was in town and walked straight into the hotel where the great French filmmaker was staying to confide in his own dreams of making a movie someday. Renoir, who was location-scouting for The River in Calcutta at the time, encouraged the aspirant. And so began the journey of the song of the little road.

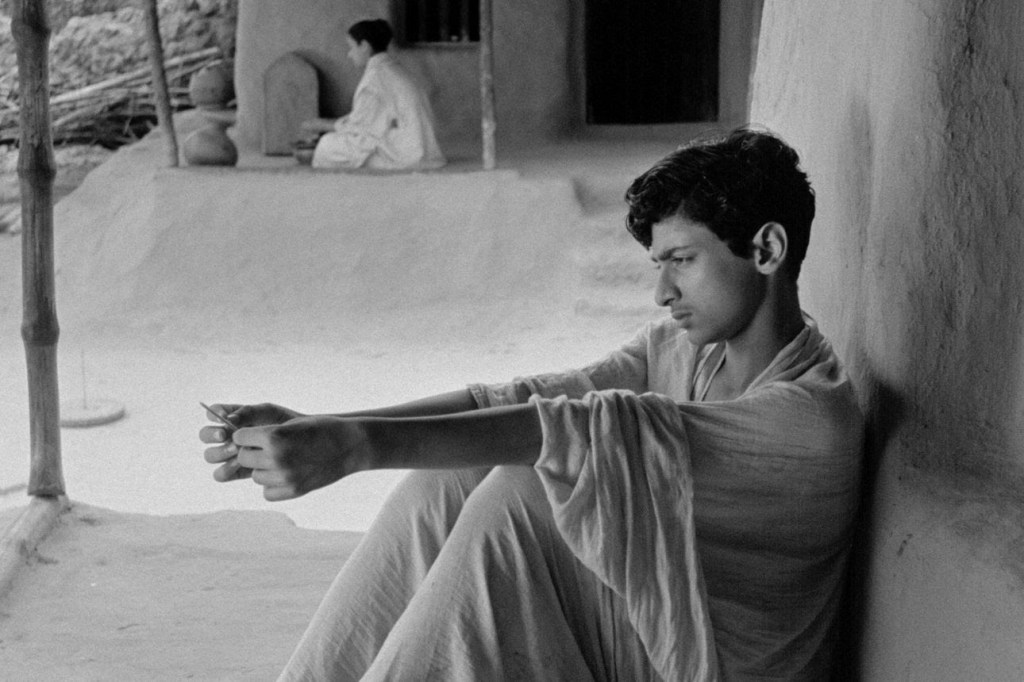

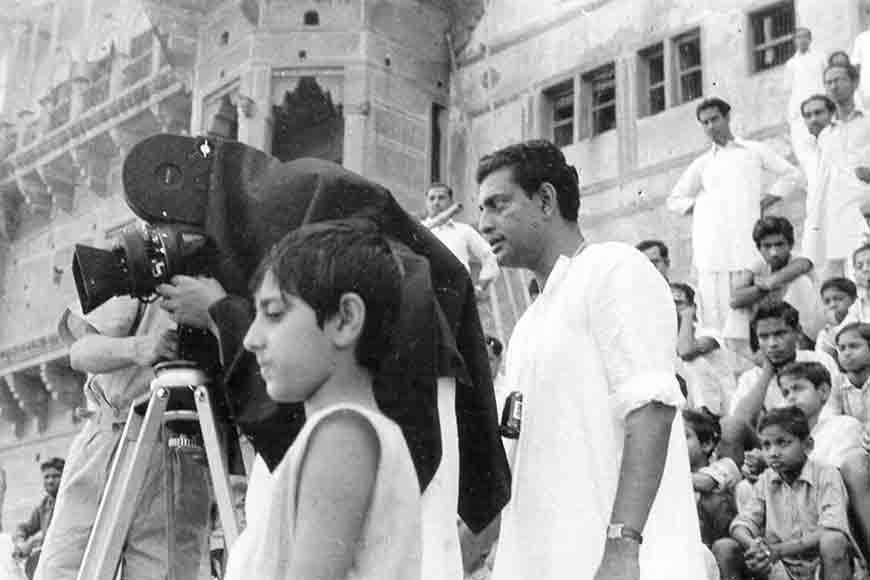

Ray’s landmark debut, Pather Panchali ( which was adapted from eponymous 1928 Bengali novel “Pather Panchali” by eminent Bengali novelist Bibhutibhusan Bandopadhay) was on a shoe-string budget in 1955 with a mostly non-professional cast. All the while, he clung on to his job for a safety net even as he shot what would become the first of the classic Apu Trilogy on weekends. The film was apparently being made by a group of neophytes, who had to stop filming more than once, owing to the depletion of their shoestring budget.

Notable Films of Satyajit Ray

Ray directed 36 films, comprising 29 feature films, five documentaries, and two short films. Pather Panchali was completed in 1955 and turned out to be both a commercial and a tremendous critical success, first in Bengal and then in the West following a major award at the 1956 Cannes International Film Festival. sured Ray the financial backing he needed to make the other two films of the trilogy: Aparajito (1956; The Unvanquished) and Apur Sansar (1959; The World of Apu). Pather Panchali and its sequels tell the story of Apu, the poor son of a Brahman priest, as he grows from childhood to manhood in a setting that shifts from a small village to the city of Calcutta.

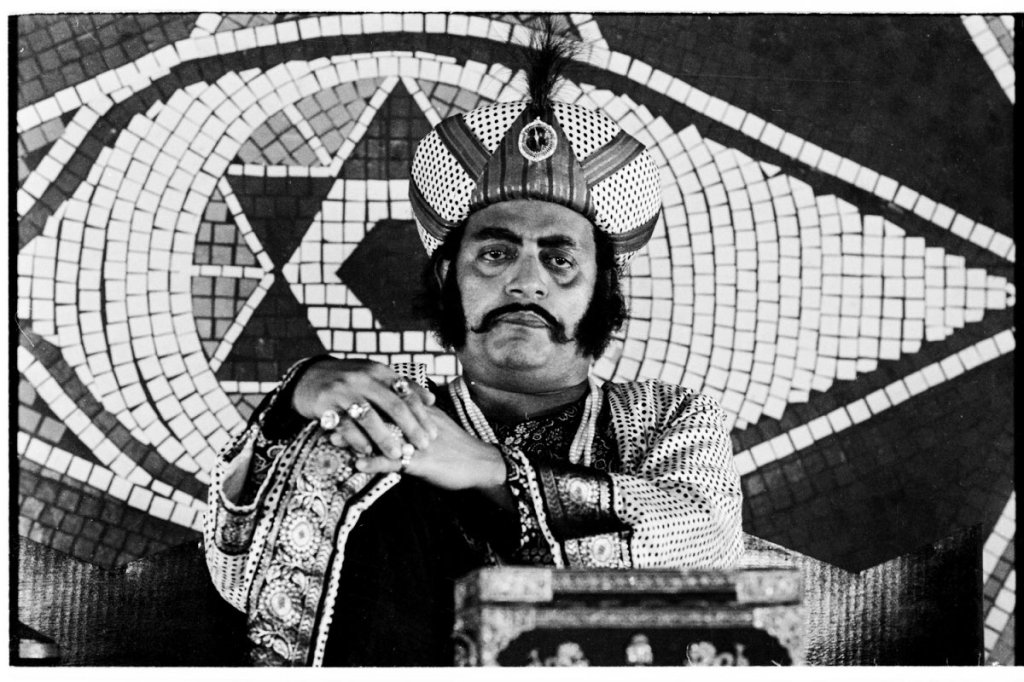

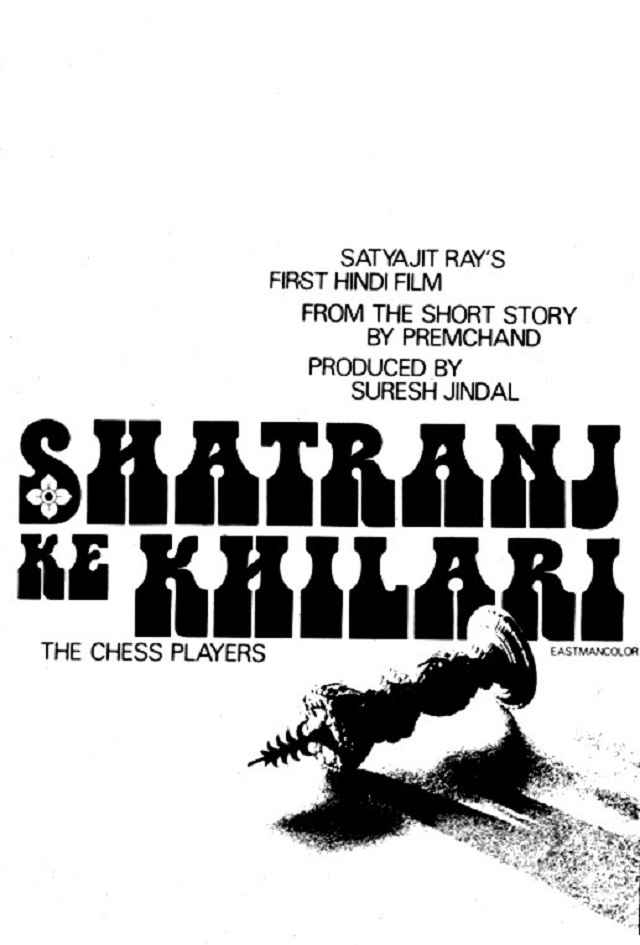

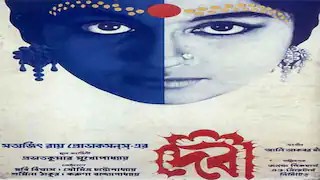

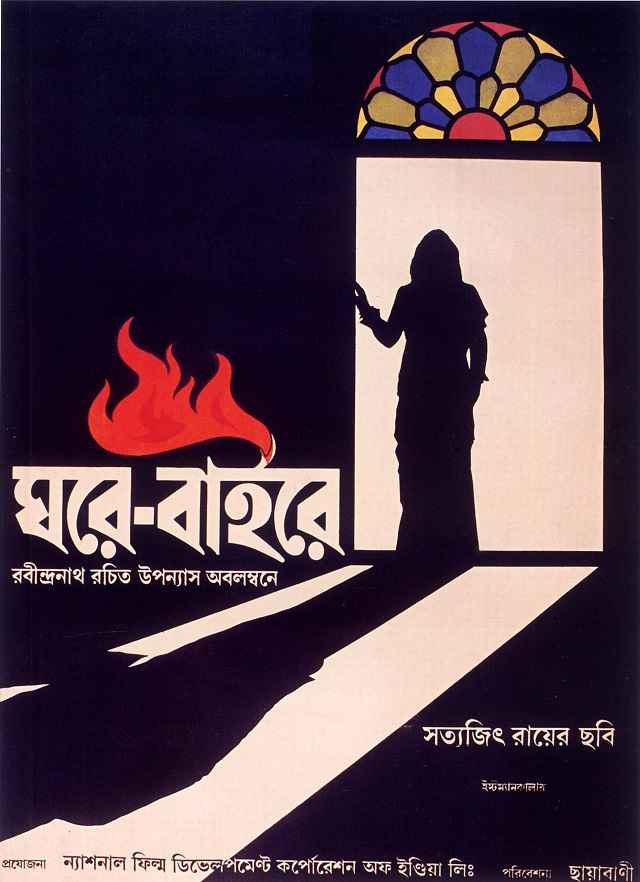

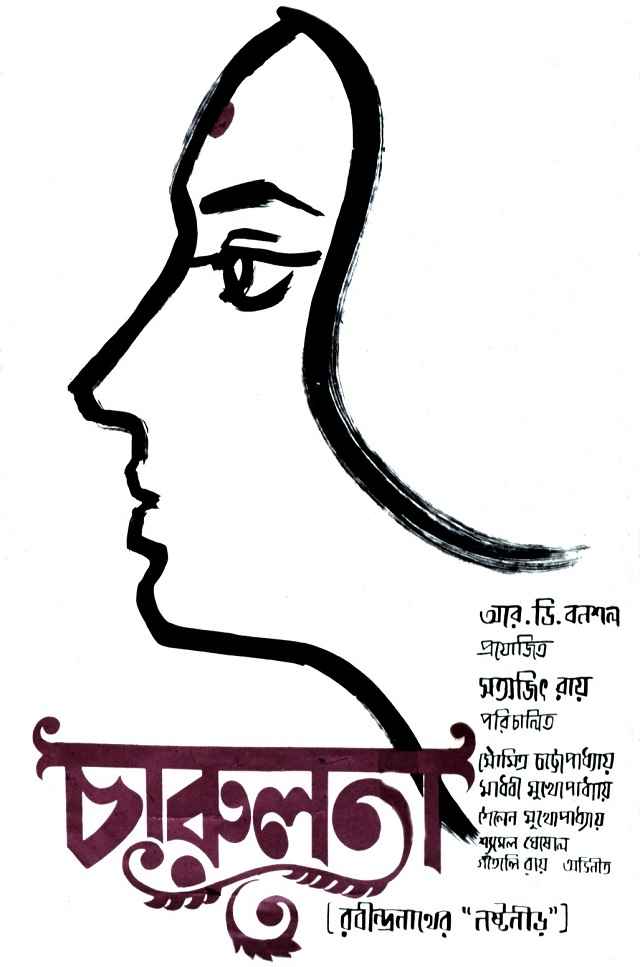

Ray’s major films about Hindu orthodoxy and feudal values (and their potential clash with modern Western-inspired reforms) include Jalsaghar (1958; The Music Room), an impassioned evocation of a man’s obsession with music; Devi (1960; The Goddess), in which the obsession is with a girl’s divine incarnation; Sadgati (1981; Deliverance), a powerful indictment of caste; and Kanchenjungha (1962), Ray’s first original screenplay and first colour film, a subtle exploration of arranged marriage among wealthy, westernized Bengalis. Shatranj ke Khilari (1977; The Chess Players), Ray’s first film made in the Hindi Language , with a comparatively large budget, is an even subtler probing of the impact of the West on India. Although humour is evident in almost all of Ray’s films, it is particularly marked in the comedy Parash Pathar (1957; The Philosopher’s Stone) and in the musical Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (1969; The Adventures of Goopy and Bagha), based on a story by his grandfather.

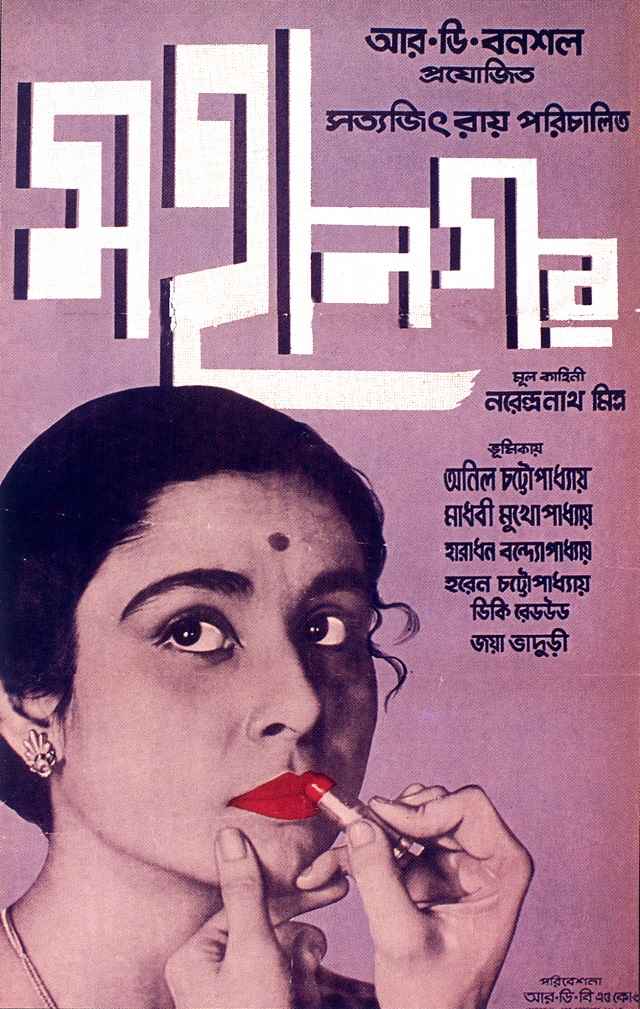

His other notable films were Ahsani Sanket (1973; Distant Thunder), Aranyer Din Ratri (1970; Days and Nights in the Forest) , Mahanagar (1963; The Big City) and a trilogy of films made in the 1970s—Pratidwandi (1970; The Adversary), Seemabaddha (1971; Company Limited), and Jana Aranya (1975; The Middleman), Ganashatru (1989; An Enemy of the People), Shakha Prashakha (1990; Branches of the Tree), and the Agantuk (1991; The Stranger).

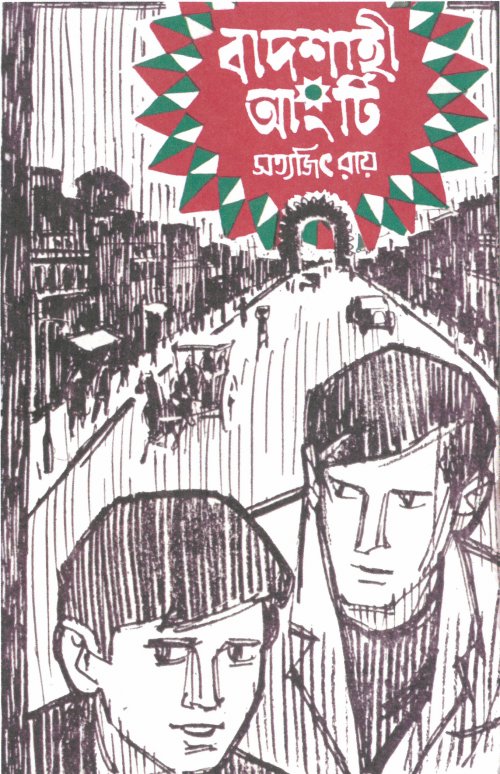

Work As A Novelist

Ray created two popular fictional characters in Bengali children’s literature—Feluda, a sleuth, and Professor Shanku, a scientist. The Feluda stories are narrated by Topesh Ranjan Mitra aka Topse, his teenage cousin, something of a Watson to Feluda’s Holmes. The science fictions of Shonku are presented as a diary discovered after the scientist had mysteriously disappeared. Ray also wrote a collection of nonsensical verses named Today Bandha Ghorar Dim, which includes a translation of Lewis Carroll’s “Jabberwocky”. He wrote a collection of humorous stories of Mulla Nasiruddin in Bengali. Ray wrote an autobiography about his childhood years, Jakhan Chhoto Chhilam (1982), translated to English as Childhood Days: A Memoir by his wife Bijoya Ray. In 1994, Ray published his memoir, My Year’s with Apu, about his experiences of making The Apu Trilogy.

Critical Analysis of Satyajit Ray

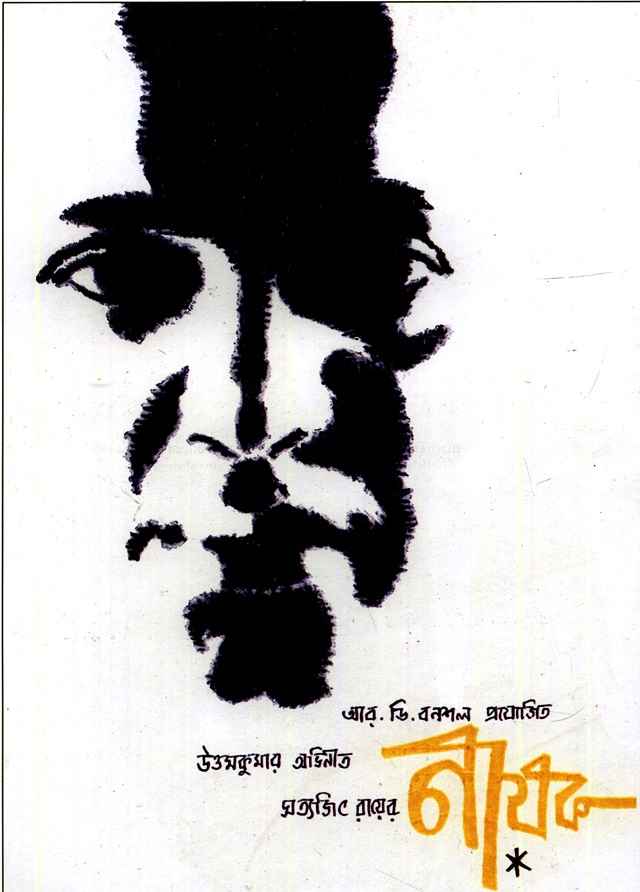

Instead of acting like a propagandist, Ray wanted to make people aware of the persistence of certain social problems. Devi and Ganasatru show people’s blind religious beliefs, Sakha Prasakhadiscloses the involvement of the top officials with bribery and corruption, Shatranj ke Khilari indicates the indolence and lack of political consciousness of the wealthy people, Aranyer Din Ratrireveals the insensitivity and boasting of the urban young men, and Mahapurush mockingly exposes the failure of the urban elite to embrace rational thoughts. Given the necessity of making people conscious of the same problems in present-day society, these films are still relevant today. Ray’s films also made a departure from tradition by frequently including strong women characters. Sarbajaya in Pather Panchali and Aparajito, Manisha in Kanchenjungha, Arati in Mahanagar, Charu in Charulata, Karuna in Kapurush, Aditi in Nayak, Aparna and Jaya in Aranyer Din Ratri, Sudarshana in Seemabadhdha, and Ananga in Asani Sanket appear as bolder, more confident, and more resilient than the male characters. In an interview, Ray states that the inclusion of unwavering women characters reflects his own attitudes towards and personal experience with women.

Awards Received by Satyajit Ray

Ray received many awards, including 36 National Film Award by the Government of India, and awards at international film festival. In 11th Moscow International Film Festival 1979, he was awarded with the Honorable Prize for the contribution to cinema. At the Berlin International Film Festival, he was one of only four filmmakers to win the Silver Bear for Best Director more than once and holds the record for the most Golden Bear nominations, with seven. At the Venice Film Festival, where he had previously won a Golden Lion for Aparajito (1956), he was awarded the Golden Lion Honorary Award in 1982. That same year, he received an honorary “Hommage à Satyajit Ray” award at the 1982 Cannes International Film Festival. Ray is the second film personality after Charlie Chaplin to have been awarded an honorary doctorate by Oxford University.

He was awarded the Dadasaheb Phalke Award in 1985, and the Legion of Honour by the President of France in 1987. The Government of India awarded him the Padma Bhusan in 1965 and the highest civilian honour, Bharat Ratna, shortly before his death. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences awarded Ray an Honorary Award in 1992 for Lifetime Achievement. In 1992, he was posthumously awarded the Akira Kurosawa Award for Lifetime Achievement in Directing at the San Francisco International Film Festival.

Conclusion

Whenever we talk about radical filmmaking in the realm of Bengali cinema, Satyajit Ray’s maiden feature (made in the face of tremendous odds) is mentioned. From Pather Panchali to his last film Agantuk, Ray never compromised on high standards, thereby making a huge impression. Having a greater familiarity with the oeuvre of Ray would enable people to understand the impressive qualities and importance of socially-meaningful cinema. We are surely in need of films that would make us perceive the beauty of a dewdrop on a blade of grass, strengthen our sense of humanism, and raise our social consciousness—hence, the everlasting relevance of the cinema of Satyajit Ray.

You must be logged in to post a comment.