Introduction

Australian author Thomas Keneally‘s novel first “Schindler’s Ark” (later republished as Schindler’s List) brought the story of Oskar Schindler’s rescue of Jewish people during the Nazi Holocaust, to international attention in 1982, when it won the Booker Prize. It was made by Steven Spielberg into the Oscar-winning film Schindler’s Listin 1993, the year Schindler and his wife were named Righteous Among the Nations.

About The Author

Thomas Michael Keneally, (born 7 October 1935) is an Australian novelist, playwright, essayist and actor. Keneally’s first story was published in The Bulletin magazine in 1962 under the pseudonym Bernard Coyle. By February 2014, he had written over 50 books, including 30 novels. He is particularly famed for his Schindler’s Ark (1982) (later republished as Schindler’s List), the first novel by an Australian to win the Booker Prize and is the basis of the film Schindler’s List. He had already been shortlisted for the Booker three times prior to that: 1972 for The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, 1975 for Gossip from the Forest, and 1979 for Confederates. Many of his novels are reworkings of historical material, although modern in their psychology and style.

Storyline of The Novel

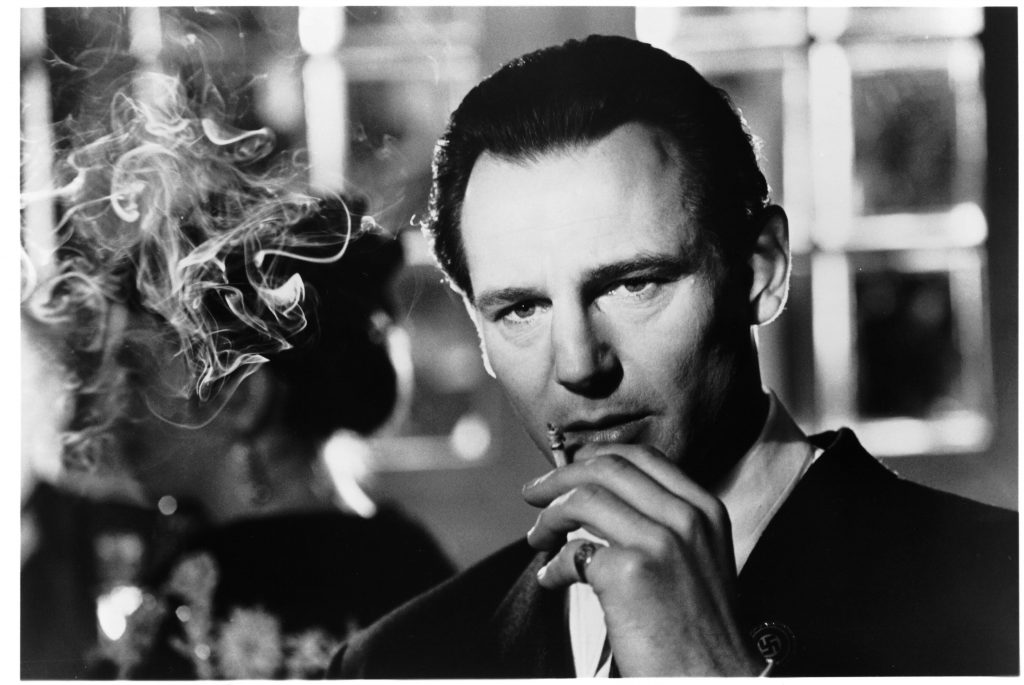

The story of the novel is based on true events, on account of the Nazi Holocaust during World War II. Oskar Schindler, (born April 28, 1908, Svitavy [Zwittau], Moravia, Austria-Hungary [now in the Czech Republic]—died October 9, 1974, Hildesheim, West Germany), German industrialist who, aided by his wife and staff, sheltered approximately 1,100 Jews from the Nazis by employing them in his factories, which supplied the German army during World War II.

In the shadow of Auschwitz, a flamboyant German industrialist grew into a living legend to the Jews of Kraków. He was a womaniser, a heavy-drinker and a bon viveur, but to them he became a saviour. This is the extraordinary story of Oskar Schindler, who risked his life to protect Jews in Nazi-occupied Poland and who was transformed by the war into a man with a mission, a compassionate angel of mercy.

Analysis of The Storyline

The novel introduced a vast and diverse cast of characters. However, the focus of the narrative was between Oskar Schindler and Amon Goeth. In the story, there was a dichotomy between what is essentially good and what is evil, that was personified by these two primary characters. Goeth represented everything evil. The war churned out a selfish and heartless sadist who found delight in inflicting pain on the Jews. Ironically, he lusted after his Jewish maid. Schindler, on the other hand, was portrayed as the Good German. He didn’t believe everything that the Nazi regime was saying against the Jews. He was, however, a man of contradictions. Despite being depicted as the epitome of goodness, he lived a self-indulgent lifestyle, which included proclivity towards the bottle and women. His infidelities have been a constant source of pain for his wife, Emilie. He also uses his connections to gain the upper hand in negotiations; it would also be a seminal part of his campaign to save the Jews.

Criticism of The Storyline

The amount of research poured to recreate the story of Oskar Schindler was astounding. And the starting point to this is as interesting as the novel itself. As noted in the Author’s Note, a chance encounter in 1980 led to the novel. Schindler’s motivation for protecting his workers was rarely ever clear, especially at the start. Questions still hound his true intentions. He, after all, brazenly took advantage of the cheap labour the Jews offered at the start of his enterprise. Is Schindler an anti-hero? The answer can be found in Keneally’s extensive research. Through interviews with surviving Schindlerjuden and different Second World War archives, he managed to identify the point in which Schindler decided to protect the Jews. While horseback riding on the hills surrounding Kraków, he witnessed an SS Aktion unfold on the Jewish ghetto below. The Jews were forcefully taken out of their houses. Those who resisted were shot dead, even in the presence of children. Witnessing the atrocious acts firsthand turned Schindler’s stomach. It was then that he resolved to save as many Jews as he can.

Overall, what didn’t work was the manner in which Keneally related the story of Oskar Schindler. As the story moved forward, it became clearer that Keneally was unsure of how to deliver the story. His resolve to remain loyal to Oskar’s story was commendable. He endeavored to do just that but it never fully came across. The result was an amalgamation of fiction and historical textbook. The strange mix muddled the story and the result was a perplexing work of historical fiction. It is without a doubt that one of the darkest phases of contemporary human history is the Second World War. Nobody expected that the meteoric ascent of Der Führer, Adolf Hitler, in the German political ladder would lead to a devastation of global scale. As the Axis forces march towards and beyond their boundaries, they would leave death and destruction in their wake, stretching from Europe, to the Pacific, and to the Far East. The consequences of the war would resonate well beyond its time. With genocides, concentration camps, and slave labour commonplace, the war was a reflection of the human conditions. Its peak, the Holocaust, exhibited the extent of the darkest shades of the human spirit. It was a grim portrait.

Indeed, the Second World War brought out the worst in humanity. However, in times of darkness, there are those among us who rise to the occasion. One of them is Oskar Schindler whose story was related by Thomas Keneally in his nonfiction novel, Schindler’s List (1982).

Conclusion

While Keneally‘s dramatization of this great man’s exploits is lacking in novelistic shape or depth, the brutality and heroism are satisfyingly, meticulously presented–as plain, impressive, historical record; and if admirers of Keneally’s more imaginative work may be disappointed, others will find this a worthy volume to place beside one of the several Wallenberg biographies.

You must be logged in to post a comment.