Citation

Mashrafi, M. A. (2026). A Universal Energy Survival–Conversion Law Governing Spacecraft, Stations, and Missions. International Journal of Research, 13(2), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.26643/ijr/2026/42

Mokhdum Azam Mashrafi (Mehadi Laja)

Research Associate, Track2Training, India

Independent Researcher, Bangladesh

Email: mehadilaja311@gmail.com

Abstract

Classical energy efficiency metrics systematically overestimate real-world system performance because they implicitly treat energy conversion as a single-stage process and neglect irreversible thermodynamic degradation. Across biological systems, terrestrial energy technologies, communication networks, and space systems, observed operational outputs fall far below laboratory or nameplate efficiencies. This discrepancy is especially pronounced in spacecraft and satellites, where fixed power budgets, radiative-only heat rejection, and strict thermal envelopes expose fundamental thermodynamic constraints.

This paper introduces a Unified Energy Survival–Conversion Law that reformulates useful energy and information production as a survival-limited, multi-stage process governed by irreversible thermodynamics and reaction–transport constraints. An energy survival factor (Ψ) is defined to quantify the persistence of absorbed energy against transport losses and irreversible entropy generation. Coupled with an internal conversion competency term derived from the Life-CAES reaction–transport framework, the resulting law

provides a universal upper bound on useful output.

Validation using independently reported data shows strong agreement with observed limits in photosynthetic ecosystems (≈1–3%), photovoltaic systems (≈15–20%), data centers (heat-dominated regimes), mobile communication networks (throughput saturation), and spacecraft subsystems (duty-cycle-limited operation). The framework explains why increasing power supply alone frequently yields diminishing or negative returns in space missions and establishes energy survival—rather than efficiency or power availability—as the governing constraint on sustainable mission performance.

Keywords: irreversible thermodynamics, spacecraft energy systems, entropy generation, energy survival, mission performance limits

1. Introduction

Across biological organisms, engineered energy technologies, communication networks, and space systems, a persistent and well-documented discrepancy exists between theoretical efficiency and realized operational performance. Component-level efficiencies—measured under controlled laboratory conditions or expressed as nameplate ratings—often suggest far higher output than is achieved at system, field, or mission scale. In practice, however, large fractions of supplied energy fail to produce useful work, information, or sustained functionality. This gap is not primarily the result of poor engineering design, measurement uncertainty, or operational mismanagement. Rather, it reflects fundamental physical constraints that are inadequately captured by classical efficiency-based formulations.

Traditional efficiency metrics implicitly assume that energy conversion is a single-stage, quasi-localized process, in which losses can be aggregated into a scalar ratio between input and output. While such metrics are convenient and remain useful for benchmarking isolated components, they systematically fail when applied to complex, multi-stage, non-equilibrium systems. In real systems, energy must propagate through multiple sequential stages—absorption, transport, regulation, conversion, control, and dissipation—each governed by distinct physical mechanisms and timescales. Losses incurred at these stages compound multiplicatively, not additively, and are often dominated by irreversible entropy generation rather than by reducible inefficiencies.

Space systems represent an extreme and uniquely revealing case of this general problem. Spacecraft and satellites operate under fixed and non-negotiable power availability, determined by solar array area, onboard generators, or radioisotope sources. Unlike terrestrial systems, they lack convective cooling and rely almost exclusively on radiative heat rejection to dissipate waste energy. Under these conditions, excess or poorly managed energy does not merely reduce efficiency; it manifests directly as thermal overload, accelerated degradation, loss of stability, or irreversible failure. As a result, spacecraft performance is frequently constrained not by how much power can be generated, but by how long absorbed energy can survive irreversible degradation before it must be rejected as heat.

Consequently, increasing power supply—through larger solar arrays, higher transmission power, or greater onboard computation—often yields diminishing or even negative returns in space missions. Payloads are duty-cycled, transmitters are throttled, and processors are underutilized to maintain thermal equilibrium. These behaviors are routinely observed across orbital platforms, including scientific satellites, communication spacecraft, and long-duration space stations. Yet classical efficiency metrics provide no general physical explanation for why such saturation occurs so consistently across missions.

1.1 Space Systems as Thermodynamic Extremes

Several defining features amplify thermodynamic constraints in space systems and render classical efficiency assumptions untenable. First, power budgets are fixed: available energy cannot be dynamically scaled to compensate for losses. Second, the absence of convection eliminates a major terrestrial pathway for heat removal, forcing all waste energy to be dissipated radiatively. Third, spacecraft components operate within narrow thermal envelopes, beyond which reliability and functionality degrade rapidly. Finally, radiative losses are irreversible: once energy is emitted to space as thermal radiation, it is permanently lost from the system.

These conditions expose thermodynamic limits that are partially masked in terrestrial systems by atmospheric cooling, grid buffering, redundancy, and economic abstraction. In space, the full consequences of irreversible entropy production are unavoidable and directly observable in telemetry and mission outcomes. Spacecraft therefore serve as a natural laboratory for identifying the fundamental physical limits governing energy utilization in real systems.

1.2 Cross-Domain Performance Saturation

Although space systems represent the most extreme manifestation, analogous performance saturation phenomena appear across a wide range of domains. In mobile communication networks, rising power consumption in successive generations of infrastructure has failed to deliver proportional gains in throughput. In data centers, increasingly efficient processors coexist with facilities that remain overwhelmingly heat-dominated. In biological ecosystems, photosynthetic organisms convert only a small fraction of incident solar energy into stable biomass, despite far higher theoretical efficiencies.

These systems differ radically in scale, function, and environment, yet they exhibit a common pattern: useful output saturates well below theoretical or component-level efficiency limits, even when energy supply is abundant. The recurrence of this behavior across unrelated domains strongly suggests the absence of a general, system-level thermodynamic law capable of explaining performance limits without resorting to system-specific explanations.

1.3 Limitations of Classical Efficiency Metrics

The root of this explanatory gap lies in the structure of classical efficiency metrics themselves. By collapsing physically distinct loss mechanisms into a single scalar ratio, efficiency obscures the origin and dominance of different degradation pathways. It provides no resolution of where energy is lost, no distinction between recoverable transport losses and irreversible entropy-generating losses, and no insight into how losses compound across sequential stages.

In space systems, this limitation becomes critical. Losses due to thermalization, electronic switching, control overhead, and radiation are not merely engineering imperfections; they are mandated by the second law of thermodynamics. Treating such losses as equivalent to reducible inefficiencies leads to systematic overestimation of achievable performance and misdirected optimization strategies that emphasize power scaling or component efficiency rather than system survival.

1.4 Objective and Contribution

This paper introduces a survival-based thermodynamic framework that explicitly treats energy utilization as a multi-stage, irreversible process. By defining an energy survival factor that quantifies the persistence of absorbed energy against transport losses and entropy generation, and by coupling it with a finite internal conversion capacity, the framework establishes a universal, experimentally falsifiable law governing useful output.

The objective is not to refine existing efficiency metrics, but to replace them with a physically complete description applicable across biological, terrestrial, communication, and space systems. In doing so, the work provides a unified explanation for long-observed performance saturation phenomena and offers a principled foundation for diagnosing limits and guiding optimization in energy-constrained systems, particularly in space environments where thermodynamic constraints are explicit and unforgiving.

2. Methods: Survival-Based Energy Formulation

2.1 Energy Survival Factor (Ψ)

Energy survival is defined as

where AE is absorbed energy reaching active functional states, TE represents transport and engineering losses, and ε denotes irreversible entropy-generating losses mandated by the second law of thermodynamics. Ψ quantifies energy persistence, not efficiency.

2.2 Ordered Energy Pathway in Space Systems

In spacecraft, energy propagates irreversibly through sequential stages: generation, conditioning, distribution, subsystem operation, payload execution, and radiative rejection. Losses compound multiplicatively, making stage-wise survival dominant.

2.3 Internal Conversion Competency (Cₙₜ)

To capture conversion limitations independent of energy survival, internal conversion competency is defined using the Life-CAES reaction–transport framework. Cₙₜ represents finite throughput imposed by spatial, temporal, architectural, and informational constraints such as Shannon capacity, processor limits, duty cycles, and orbital geometry.

2.4 Unified Energy Survival–Conversion Law

The two independent constraints combine multiplicatively:

This law applies irrespective of energy source, gravity, or operating environment.

2.5 Measurement and Falsifiability

All terms are independently measurable using standard telemetry, thermal sensors, and performance logs. No fitting parameters are introduced, satisfying falsifiability criteria for a physical law.

3. Results

3.1 Biological Systems

Across terrestrial photosynthetic ecosystems, the estimated energy survival factor consistently falls in the range Ψ ≈ 0.01–0.03 when evaluated at ecosystem or biosphere scale. This corresponds to net primary productivity values of approximately 1–3% of incident solar radiation, in agreement with long-term field measurements and satellite-derived global productivity datasets. The low survival factor arises from cumulative losses during spectral mismatch, radiative relaxation, non-photochemical quenching, metabolic maintenance, and respiration. Importantly, these losses compound across multiple biochemical and structural stages rather than occurring at a single conversion step, resulting in a survival-limited regime even in systems that have undergone extensive evolutionary optimization.

Empirical evidence further shows that increasing solar energy input does not yield proportional increases in biomass production. Under high irradiance, excess absorbed energy is preferentially dissipated as heat or induces photoinhibition, reducing survival rather than increasing useful output. This behavior is consistent with the survival-based formulation, in which additional input energy increases entropy generation when survival pathways are saturated. The observed saturation of biological productivity therefore reflects a fundamental thermodynamic constraint rather than nutrient limitation or ecological inefficiency, validating the applicability of the survival factor Ψ as a governing parameter in naturally optimized systems.

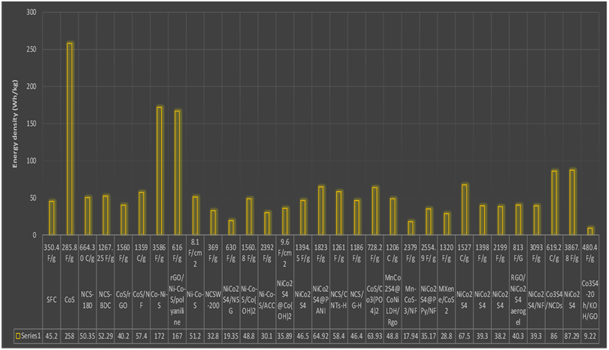

3.2 Engineered Energy Systems

In engineered terrestrial energy systems, utility-scale photovoltaic plants exhibit moderate energy survival, typically Ψ ≈ 0.7–0.8, reflecting losses from optical reflection, thermal derating, power conditioning, inverter inefficiencies, and transmission. Despite continuous improvements in module-level conversion efficiency, annualized net electricity delivery remains constrained to approximately 15–20% of incident solar energy. This outcome is well predicted by the unified survival–conversion formulation when bounded internal conversion competency is included, accounting for carrier recombination, current-density saturation, and grid-interface constraints.

Data center infrastructures present a contrasting engineered benchmark characterized by high energy availability but severely limited internal conversion competency. Although modern processors achieve high computational efficiency at the device level, system-level measurements show that the majority of supplied energy is dissipated as heat through cooling, power distribution, and idle operation. Estimated values of Cₙₜ are typically on the order of 0.01–0.05, placing data centers firmly in a conversion-limited regime. The resulting heat-dominated operational state persists despite aggressive efficiency improvements, demonstrating that performance saturation arises from bounded conversion capacity rather than insufficient energy supply.

3.3 Communication Networks

Mobile communication networks exhibit intermediate survival factors, typically Ψ ≈ 0.15–0.35, as derived from field measurements of base-station power consumption, cooling overhead, backhaul transport, and RF propagation losses. A substantial fraction of supplied energy is consumed by always-on control signaling, synchronization, and idle operation, even during periods of low traffic demand. These survival losses reduce the fraction of energy that reaches active data transmission and processing states, placing a hard upper bound on achievable throughput per unit input energy.

At the same time, internal conversion competency in mobile networks is strongly bounded by Shannon capacity limits, modulation and coding constraints, scheduling inefficiencies, retransmissions, and user mobility. As a result, increasing transmission power or network density does not yield proportional gains in delivered data rates once these limits are reached. Observed throughput saturation in mature 4G and 5G deployments is therefore consistent with the unified law, in which moderate survival and bounded conversion jointly constrain useful output. Rising network energy consumption without commensurate throughput gains emerges naturally from these first-principles limits.

3.4 Spacecraft and Satellites

Spacecraft and satellite systems operate under moderate survival factors, typically Ψ ≈ 0.25–0.45, reflecting losses from solar conversion, power conditioning, distribution, thermal control, and subsystem overhead. Telemetry consistently shows that a significant fraction of onboard power is devoted to survival functions—such as attitude control, thermal regulation, and redundancy—rather than to mission output. Because all waste energy must ultimately be rejected radiatively, entropy generation directly constrains continuous operation, making survival a dominant performance limiter in space environments.

Internal conversion competency in space systems is further bounded to Cₙₜ ≈ 0.05–0.25 by communication windows, onboard processing limits, radiation-hardened hardware, orbital geometry, and thermal duty-cycle constraints. These bounds explain why payloads are rarely operated continuously and why increasing solar array area or transmission power alone does not increase delivered data or scientific return. Instead, excess energy accelerates thermal saturation and forces reduced duty cycles. The resulting duty-cycle-limited operation observed across satellites and space stations is therefore a direct consequence of survival and conversion limits, not of insufficient power generation.

4. Discussion

4.1 Survival Dominance and the Weakest-Link Principle

A central implication of the Unified Energy Survival–Conversion Law is that overall system performance is governed by the lowest survival stage along the energy pathway rather than by the most efficient component. Because survival factors across sequential stages compound multiplicatively, even modest losses at a single stage can dominate system-level outcomes. This “weakest-link” behavior explains why systems composed of highly optimized components frequently exhibit disappointing aggregate performance. Improvements applied to already efficient stages—such as marginal gains in solar cell efficiency or transmitter electrical efficiency—yield diminishing returns when survival is constrained elsewhere, particularly by thermal rejection or duty-cycle limitations.

This principle clarifies a long-standing disconnect between component-level optimization and system-level results. Traditional design strategies often focus on improving peak efficiency metrics because they are measurable and locally actionable. However, when energy survival is dominated by a downstream bottleneck, such improvements do not translate into increased useful output. The survival-dominance framework therefore shifts analytical emphasis from identifying the best-performing component to identifying the most destructive stage, where irreversible losses suppress all upstream gains. This reorientation has broad implications for system diagnosis and optimization across energy, communication, and space systems.

4.2 Thermal and Entropy Constraints in Space

In space systems, thermal and entropy constraints emerge as the most stringent survival limiters. Because radiative emission is the only viable mechanism for heat rejection, the rate at which entropy can be expelled to space establishes a hard upper bound on continuous operation. Once this bound is reached, additional energy input cannot be converted into useful work and instead accelerates thermal accumulation, forcing throttling or shutdown. This constraint is absolute rather than economic or technological, as it arises directly from radiative physics and the second law of thermodynamics.

Consequently, performance gains in space missions are dominated by thermal-first design strategies rather than power scaling. Enhancements such as improved heat transport, radiator effectiveness, emissivity control, and thermal architecture directly increase energy survival by slowing entropy accumulation. Similarly, duty-cycle optimization and entropy-aware scheduling allow systems to operate closer to survival limits without exceeding them. These approaches often yield greater mission productivity than increasing generation capacity, providing a formal thermodynamic justification for design practices long recognized empirically in spacecraft engineering.

4.3 Resolution of Energy Paradoxes

The survival-based framework provides a unified resolution to several long-standing energy paradoxes observed in both telecommunications and spacecraft systems. In mobile networks, rising power consumption has not produced proportional increases in delivered throughput, despite continuous improvements in hardware efficiency. Similarly, in spacecraft, increasing solar array size or transmission power frequently fails to increase mission output. Classical models struggle to explain these phenomena without invoking ad hoc inefficiencies or operational shortcomings.

Under the Unified Energy Survival–Conversion Law, these paradoxes arise naturally when survival factors or conversion competency saturate. Once irreversible entropy generation or bounded throughput dominates, additional power increases losses rather than output. Power supply, therefore, ceases to be the controlling variable for useful performance. This explanation requires no system-specific tuning and applies equally to digital networks and space platforms, demonstrating that the observed paradoxes are not anomalies but predictable consequences of fundamental thermodynamic constraints.

4.4 Universality of the Law

A defining strength of the proposed framework is its universality across domains. The same governing law applies to ecosystems, engineered machines, information networks, and spacecraft without modification. Differences in observed performance arise from variations in survival factors and conversion competency, not from different underlying physics. This universality confirms that energy survival and bounded conversion are fundamental constraints that transcend scale, technology, and environment.

Importantly, the law remains valid across radically different operating conditions, including atmospheric and vacuum environments, biological and artificial systems, and terrestrial and extraterrestrial settings. Gravity, medium, and energy source influence parameter values but do not alter the governing relationship. This invariance establishes the Unified Energy Survival–Conversion Law as a genuine system-level physical law rather than a domain-specific model, providing a common language for analyzing performance limits across traditionally disconnected fields.

5. Conclusions

This study establishes energy survival as a first-order physical constraint governing useful energy and information production in real systems. By explicitly incorporating irreversible entropy generation, transport degradation, and bounded conversion capacity, the Unified Energy Survival–Conversion Law provides a thermodynamically complete description of system performance that extends beyond classical efficiency, exergy, or energy-per-output metrics. The framework demonstrates that useful output is limited not by how much energy is supplied, but by how long absorbed energy can persist without being irreversibly degraded and how effectively surviving energy can be converted within finite structural and temporal constraints. In doing so, it offers a unified explanation for the widespread and recurring saturation of performance observed across biological ecosystems, engineered energy technologies, communication networks, and space systems.

By replacing scalar efficiency with a survival-based system-level metric, the proposed law resolves long-standing discrepancies between theoretical performance and operational reality. It explains why improvements in component-level efficiency or power availability often fail to translate into proportional gains at mission or infrastructure scale and clarifies why thermal management, duty cycling, and architectural optimization dominate real-world outcomes. Importantly, the law is experimentally falsifiable and relies exclusively on independently measurable quantities, reinforcing its status as a physical constraint rather than a phenomenological or empirical model. As such, it provides a common analytical language for diagnosing dominant loss mechanisms, predicting realistic performance ceilings, and guiding optimization strategies across domains that have traditionally been treated as physically distinct.

Future research directions naturally follow from this survival-centered perspective. Immediate extensions include application to deep-space missions, where long durations, extreme thermal environments, and communication delays further amplify survival and conversion constraints, as well as to nuclear-powered and hybrid spacecraft, enabling systematic comparison of entropy generation across fundamentally different energy sources. At larger scales, constellation-level survival modeling can capture collective losses arising from coordination overhead, inter-satellite links, and network-level entropy production. Finally, the development of survival-aware control, scheduling, and autonomy algorithms offers a promising pathway for translating the theoretical framework into operational gains, particularly in space systems where power and thermal margins are inherently unforgiving.

References

Carnot, S. (1824). Réflexions sur la puissance motrice du feu. Bachelier.

Clausius, R. (1865). The mechanical theory of heat. Philosophical Magazine, 30, 513–531.

Gibbs, J. W. (1902). Elementary principles in statistical mechanics. Yale University Press.

Prigogine, I. (1967). Introduction to thermodynamics of irreversible processes. Wiley.

Bejan, A. (2016). Advanced engineering thermodynamics (4th ed.). Wiley.

Szargut, J., Morris, D. R., & Steward, F. R. (1988). Exergy analysis of thermal, chemical, and metallurgical processes. Hemisphere.

Field, C. B., Behrenfeld, M. J., Randerson, J. T., & Falkowski, P. (1998). Primary production of the biosphere. Science, 281, 237–240.

Blankenship, R. E., et al. (2011). Comparing photosynthetic and photovoltaic efficiencies. Science, 332, 805–809.

Shockley, W., & Queisser, H. J. (1961). Detailed balance limit of solar cells. Journal of Applied Physics, 32, 510–519.

Landauer, R. (1961). Irreversibility and heat generation in the computing process. IBM Journal of Research and Development, 5, 183–191.

Wertz, J. R., Everett, D. F., & Puschell, J. J. (2011). Space mission engineering: The new SMAD. Microcosm Press.

Gilmore, D. G. (2002). Spacecraft thermal control handbook. Aerospace Press.

Bejan, A., & Lorente, S. (2010). The constructal law. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 365, 1335–1347.

You must be logged in to post a comment.