The task at hand is twofold : first, to present a schematic account of feminism in India ; second to bring up some theoretical and methodological issues entailed in representing it. This decision to problematize the process of narrating has been prompted by the fact that writing in the second decade of the 21st century implies that we take into cognizance some of the developments in the preceding decades that impinge in a very fundamental way on both the practice and theory of feminism. In other words, I seek to flag some of the changing features of the contemporary context within which I as a resident Indian scholar write about feminism for Western academia. (i) A rich and complex body of feminist writings has emerged over the last forty years which in many ways have become institutionalized within academia as well as within policy making, whether of various states or of international agencies ; (ii) the rise of multiculturalism and postmodernism in the West since the 1980s gave way not just recognition but celebration of diversity and plurality including that of divergent feminisms ; (iii) the rise of postcolonial studies, articulated in the writing of non-Western scholars located in the West on one hand and a predilection towards poststructuralist theory on the other ; (v) finally the greater visibility of India and Indian scholarship in the recent decades of globalization. My central contention is that these developments are not extraneous but constitutive of Indian feminism.

As a resident Indian feminist scholar I feel an acute sense of disquiet when what I have to say is readily slotted as yet another instance of burgeoning postcolonial writings, one more voice of diverse feminism. My discomfort is that postcolonial theory principally addresses the needs of Western academia. “What post-colonialism fails to recognize is that what counts as ‘marginal’ in relation to the West has often been central and foundational in the non-West” . Thus when I privilege British colonialism and Indian nationalism this is not a belated deference to postcolonial theory but a historical fact which Indians have lived and battled with and one within which the story of Indian feminism emerged and grew. Further, the theoretical shift to textual analysis that accompanied postmodernism and post structuralism led to a gross neglect of a historical and concrete analysis of the constraints of social institutions and the possibilities of human agency therein.

I start on this note to make a conscious break with concepts in circulation and a current academic propensity, which invokes ‘difference’ and ‘plurality’, celebrates ‘fragments’ in a manner of politically correct mantras without even being fully aware of the complex and concrete historical processes, which produce and perpetuate these differences and inequalities. Social institutions, production relations, individual and group actions (and reactions), retreat from such analysis while attention is focused on discerning ‘ruptures’ and ‘gaps’ in either textual representations or oral narratives. These ruptures appear like autonomous ‘marks’ awaiting discovery from the analyst rather than real, historically existing social contradictions.

In privileging India’s colonial past, I am not averring to a simple colonial social constructionist position, nor waving the wand of colonial cartography. I begin with the material and ideological dynamics of colonialism within which Indian feminism emerged and developed – a past that makes its presence felt in some expected and many unexpected, unintended ways as this paper would show. I therefore choose to understand the emergence of feminism in India in the following contexts :

history of colonialism and emergent Indian nationalism ;

its subsequent advance within the trajectory of independent India’s state initiated development ;

more recently within the transformed context of globalization and India’s own success story in it ;

and growing assertion of marginalized castes and communities which has led to a complex deepening of the democratization process in India.

While I have often been asked to tell the story of Indian feminism, I have in each instance been acutely aware of the convolution involved. The academic context of knowledge practices within which I write today about Indian feminism for a Western audience is only a part of the complexity. Though Western hegemony is not quite what it used to be, it is not easy to rid ourselves of our ‘captive imagination’ – a point that was driven home to me almost a decade ago as I struggled to write a conceptual story of feminism in India. I realized :

“the obvious but often overlooked fact that while, for western feminists whether or not to engage with non-western feminism is an option they may choose to exercise, no such clear choice is available to non-western feminists or anti-feminists. (…) our very entry to modernity has been mediated through colonialism, as was the entire package of ideas and institutions such as nationalism or democracy, free market or socialism, Marxism or feminism. Any question therefore, had to confront the question of western feminism as well…”

What then is different today ? I would argue that while we had a great deal of interaction with the colonial West, we did not have the kind of increasingly institutionalized global academic interaction which we have today, a world where too often we all appear to speak alike, even when we seek to mark our difference. The earlier Western ideological influence and the opposition to it were both more powerful and explicitly political. The native was speaking but her voice was outside the deemed legitimate intellectual discourse. It was in the political sphere of colonial India that social reformers and nationalists sought to make history, sought to articulate a distinct nationalist and feminist identity (though informed of and often inspired by Western visions). Often this expressed itself as a denial. “I am not a feminist” was a statement heard more often than not from major women public figures. My argument has been that “the sheer persistence of this theme has a story to tell”. And the story is that ambivalence/evasion can be fruitfully read “both as a claim for difference as well as political strategies of the nationalist and women’s movement” (Chaudhuri, 2011b, p. xix). Readers will appreciate that those rough and turbulent struggles of feminist doings in colonial times within which feminism was being theorized were very different from the current, sanitized academic spaces where professionals seek to speak and write, no matter how many times the word ‘political’ is invoked. No wonder I had found it impossible to separate the history of action from the history of ideas, and in an intellectual world so completely subjugated by Western academic norms it took a while to recognize :

“that feminism was being debated, but differently, (…) such attempts at articulating difference were taking place in a context uninformed either by the language of difference or the more recent political legitimacy accorded to it… concepts which have ‘local habitation and name’ today and which slide spontaneously to the tip of the tongue and pen (‘gender construction, ’ ‘patriarchy’, ‘empowerment’, ‘complicity’, ‘co-option’) were couched in different labels a century ago.”

My location as a resident Indian is important even in such times of times of globalization. Not only do I have to engage with the West, but a West with an increasing presence of the non-West and a Western academia, where the ‘native’ has already spoken. Postcolonial scholars of South Asian origin are leading intellectual voices of the non-West in the West, particularly North America. This compounds the matter more, for ‘national’ contexts do still matter in social sciences and humanities. At another level, many of the issues that at one time appeared to be issues of the non-West are now eminently visible in the West, home to increasing and strident cultural diversity. At one time ‘Western-located Indian’ feminists decried the fact that Indian feminism was “self effacing”, that Indian women see their personal desires as unnecessary and were engrossed with larger questions such as questions of community identity, democratic citizenship, religious beliefs, workers’ rights, cultural distinctions, and rural poverty. The question that Western feminisms would ask and we would echo : “Where amidst this din of large issues were the women ?”.

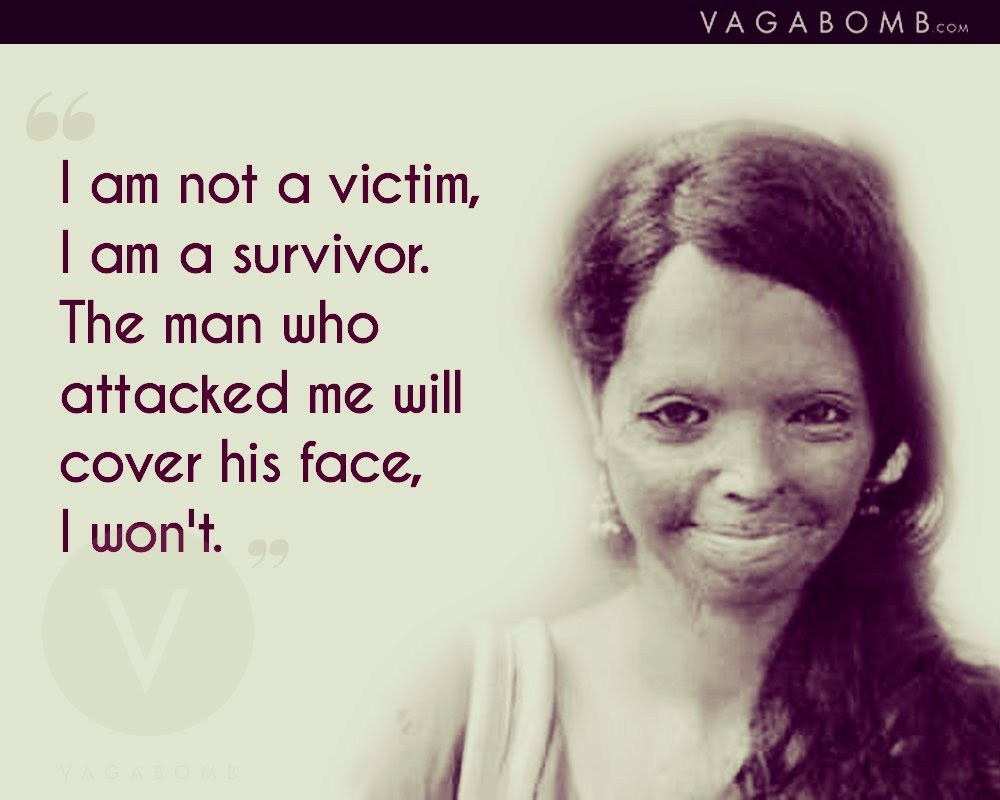

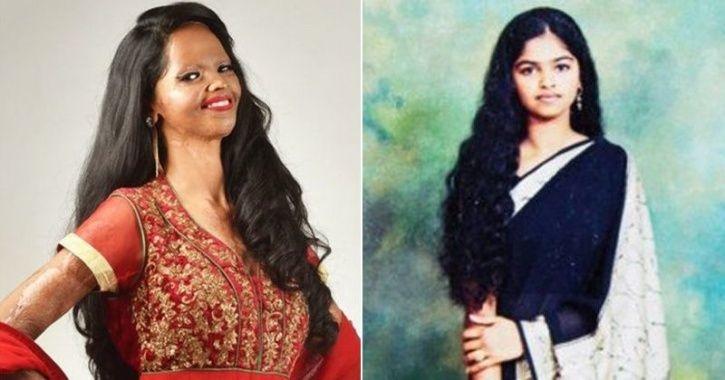

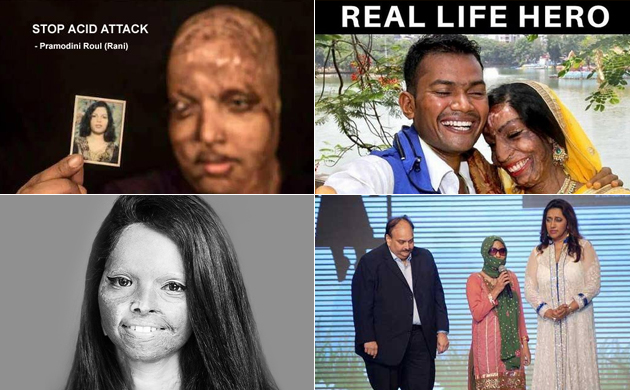

A decade into the 21st century, the terms of the debate seem to have changed entirely in the West. It seems overtly obsessed with questions of cultural identity, of alien cultures and a realization that choices and selfhoods need not be expressed in the language of the Western individual woman. In a world politically more intolerant than ever, in a Western academia more multicultural than ever, the histories of non-Western feminisms no longer appear extraneous, beside the point, or even lacking the ‘authentic’ feminist impulse. Almost lurching to the other extreme, voices of non-Western women are now validated in the West. Alternative modes of agencies are being increasingly imagined. I am a trifle wary of the representation of the third world woman either as “victim subject” or as an “alternate agential self” – catch-all terms that reign in postcolonial Western academia. It is in such a context that it may be productive to shift focus to the ground reality of Indian feminist deliberations such as that of the Thirteenth National Conference of the Indian Association of Women’s Studies (IAWS) 2011, the largest national-level body of Indian feminists. Here we find a context that is far more complex and manifold, and concepts that are far more varied. In contemporary Indian feminism we thus have issues ranging from :

developmental induced displacements to questions of alternative sexuality ;

agrarian crisis to the need to challenge hierarchies of victimhood versus pleasure ;

reproductive health to the question of controlling resources – land, forest and water ;

global capitalism and the localized and diverse articulations of culture to military conflict ;

language, voices representations to new markets and interlocking inequalities ;

rural labour to women in religions ;

starvation to female spectatorship.

The above issues are not exhaustive. They are simply indicative of the unequal and diverse voices WITHIN contemporary Indian feminism .

Inequalities and diversities define Indian society. Various precolonial social reformer movements, the British state, the nationalist and feminist movement have always had to negotiate with this. Thus British colonialism impacted different regions differently both because of the stage of colonialism as well because of the nature of different regions. Thus there were periods of reluctance on the part of colonial rulers’ meddling with India’s social customs such as those related to women, for fear of reprisal, and periods of active involvement to intervene such as the abolition of sati in 1829 or raising the Age of Consent for Women in 1863 which brought forth a furiously hostile reaction, leading again to a phase where the British preferred to rely more on their conservative allies. What one can however infer is that colonial rule, the humiliation of the subject population, the impact of Western education, the role of Christian missionaries, growth of an English speaking Indian middle class all led to an intense and contested debate of the women’s question in the public sphere. This debate itself has been scrutinized carefully from different perspectives. We thus have a question on whether the debate on sati was about women or about reconfiguring tradition and culture ; we have questions on why Dalit women’s public initiatives and intervention went unwritten; we have arguments that suggest social reforms were more about efforts to introduce new patriarchies than about women’s rights and gender justice. Such rethinking emerges from the challenges posed by social movements and new theorizing emanating from structural transformations within the country.

The Indian feminist is debating in part within the ‘national’ context on ‘local’ issues, even as she is part of the contemporary globalization of academia and of feminist scholarship. That there is such a strong presence of scholars of Indian origin within Western academia who speak for India but within an intellectual world quite distinctively Western, with its own set of empirical and conceptual imperatives, compounds the matter further. Concepts travel thick and fast and are often picked up without any serious engagement with either their contexts or with the theoretical frameworks from which concepts emerge.

Readers will excuse this digression. For I think that, at this present historical juncture where intellectual international exchanges are both intensive and far reaching, one needs to problematize the contexts of production, circulation and reception of intellectual representations. It is necessary therefore to draw attention to the fact that “texts circulate without their context…. and… the recipients, who are themselves in a different field of production, re-interpret the texts in accordance with the structure of the field of reception.” The concepts with which I seek to tell the tale of Indian feminisms needs historicizing. Further, the theoretical frameworks that have sought to analyze the history of Indian feminisms are themselves products of social movements such as the anti-colonial, the nationalist, the feminist, the left and anti-caste. Simply put, much before the theoretical shift to a language of difference, Indian social movements – whether nationalist or feminist – have had to negotiate with both the questions of difference and inequality.

The 20th Century Movement

Prior to the 1990s, the Indian state visualized a state-led development in alliance with national capital (Chaudhuri, 1996). The 1990s altered this paradigm. Transnational capital and the market acquired ascendancy. This shift reconfigured both class and gender in the developmental priority, and therefore necessarily in the national imaginary. Readers will recall how the Indian working class and peasant women were seen as the face of the nation.

This ideological frame changed. The national iconic representation of the working class and peasant women gave way to the new icons of Brand India – the super rich, the beautiful people of the now growing Beauty Business. The buzzword was ‘growth’ and the way towards it an ‘unbridled market’. Structurally, deregulation was the way forwards. One of the corollaries of this pattern of development was an unprecedented expansion of the informal sector wherein a large section of women worked on wretchedly low wages with no security of tenure. Feminists like Mary John and U Kalpagam (1994) have observed how this model has been legitimized by international institutions like the World Bank who have drawn upon feminist scholarship about “the incredible range of tasks poor women perform, their often greater contribution to household income despite lower wage earnings, their ability to make scarce resources stretch further under deteriorating conditions”, but through a crucial shift in signification displayed the findings as no longer arguments about “exploitation so much as proofs of efficiency” (John, 2004, pp. 247-248). Not surprisingly, a great deal of development gender discourse is now exclusively addressed within the micro credit framework, premised upon the idea that women are efficient managers and can be trusted to repay.

Significantly, while most feminists were critical of the state relegating its commitment to the poor and vulnerable, there were contrary views. Gail Omvedt for instance contends that “being anti-globalisation” has become the correct standard of political correctness and argues that “the only meaningful question is, for a Marxist (or dalit, or feminist) activist, what advances the revolution, that is, the movement towards a non-caste, non-patriarchal, equalitarian and sustainable socialist society ?” (Omvedt, 2005, p. 4881) Sections within the Dalit movement itself have aggressively projected the need for dalit capitalism and globalization as the way forward (Chaudhuri, 2010).

I have already alluded to the rise of the Beauty Business which was closely tied to an unprecedented expansion of the advertising and consumer goods sector, which together recast the Indian woman from the frugal to the profligate spender – in keeping with the changing image of India (Chaudhuri, 2000, 2001). It is impossible to capture the finer contours of the feminist debates in this context. A quick reference to the diverse takes on a major Beauty Contest that was organized in Bangalore in 1997 may capture the key points. The contest was marked by protests by the women’s movement against beauty contests on the grounds that “these contests both glorify the objectification of women and serve to obscure the links between consumerism and liberalization in a post-globalization economy”. Processions were held in Bangalore with mock ‘queens’ crowned as ‘Miss Disease’, ‘Miss Starvation’, ‘Miss Poverty’, ‘Miss Malnourished’, ‘Miss Dowry Victim’, etc. in order to highlight the issues of poverty, and lack of nutrition and health care in the country (Phadke, 2003, p. 4573). Shilpa Phadke, a younger generation feminist, argues in this context that “the focus on women as ‘victims’ could well serve to erase images of women as subjects with agency, sometimes suggesting that feminism is a movement devoid of joy”. She further argues that the market rather than the state is better as “a potential turf for negotiation”. For “unlike the state, where the citizen is largely a client, for the market the individual is first and foremost an actor-consumer. Can the women’s movement use the strategies of the market to re-sell itself to a larger audience and reclaim its right to speak on behalf of a larger constituency of women ?” (ibid., p. 4575) It is important to reiterate here that many continue to perceive the state and political parties rather than the market or NGOs as responsible for their “basic needs”, and they approached either the government agency concerned or political parties when they needed resolution of any problem (Chandhoke, 2005). The great Indian middle class may not need the government, but the vast majority of the poor do. The idea of citizenship as both hegemonic and potentially liberating has been very central to Indian feminism (Roy, 2005). Into the second decade of the 21st century, Indian feminism is engaged with a whole host of issues – some global, some not.

The conclusion

The central contention that has informed this paper is that while boundaries (including academic) are increasingly breaking down, there still exist considerable distinctions between the global and local, the West and non West. And here, I am not alluding to any idea of an essential culture, or to notions of pure indigenous concepts, but only to the specificities of history. Western concepts of the state and market, citizen and consumer hold here as much as anywhere else. This paper bears witness to this. What differ are the details that make the stuff of human action and human conceptualization. The context, within which concepts emerge and the contexts where they travel to, needs enunciation. Its significance in an increasingly globalized academia cannot be overstated. Hence the focus here is on both the tale and the telling of Indian feminism. No ready conceptual frame of the postcolonial, even less no seductive binary oppositions, no amount of sophisticated readings of textual representations will suffice. Endless invocation of ‘voices’ and ‘agency’ will not set free the elusive feminist subject. Careful historical analysis may offer a better understanding of the many achievements and failings of Indian feminism.

You must be logged in to post a comment.